In the time between the two imperialist wars, the spirit and politics of Pan-Africanism grew. African Americans continued to organize and built movements to resist rising fascism.

Originally published in Fighting Words.

In the aftermath of the First Imperialist War [World War I], African Americans and people of African descent around the world escalated their movements to end colonial domination, legalized segregation and the super-exploitation of their land, resources and labor.

The Pan-African Congress held in Paris during 1919 represented a turning point in the political consciousness and organizational capacity of the Black masses globally.

A central figure in this process was Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the co-founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) in 1909. Du Bois was a graduate of Harvard University in 1896 where he wrote his Ph.D. Dissertation on the suppression of the African slave trade.

By 1900, Du Bois was involved in the Pan-African Conference held in London from July 23-25. After WWI, the historian and social scientist, in response to the Paris Peace Conference, called for another gathering, this time entitled the Pan-African Congress.

Although the resolutions of the Pan-African Congress in Paris during 1919 were limited in their militancy due to the strength of imperialism even in the wake of the pillage involving millions during the war, the gathering was a clear reflection of the heightened consciousness of peoples throughout the oppressed nations. In that same year, the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was founded by African workers in Cape Town, South Africa where it embarked upon an unprecedented strike against racism and exploitation.

Also in the summer of 1919, white racist mobs backed by police and national guardsmen invaded African American communities in cities such as Chicago, Knoxville and Washington, D.C. attacking, robbing, burning and murdering African American people. However, in contrast to the lynchings in the rural and urban South, veterans from the war organized defense brigades where they fought back with a vengeance against the racists.

Consequently, the stage was set for a surge in organizations advocating armed self-defense, desegregation, Socialism, Nationalism and Pan-Africanism. Du Bois had established “The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races” in 1910 just one year after the NAACP was founded. The magazine played a pioneering role in the development of what became known as the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

The Role of Jessie Redmon Fauset in the Harlem Renaissance and Pan-Africanism

In 1919, Du Bois recruited educator and writer Jessie Redmon Fauset and appointed her as the literary editor of The Crisis. Fauset had been born into an impoverished family in New Jersey in 1882.

Despite her humble origins she was able to excel academically at the Philadelphia High School for Girls and later won a scholarship to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Fauset earned a bachelor’s degree at the Ivy League institution in classical languages and literature in 1905. Later she received a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1919. She would work as a high school teacher in Washington, D.C. while gaining recognition as a poet and writer of short stories, essays and novels.

As literary editor of The Crisis she was described by legendary poet, novelist, composer, playwright and public intellectual Langston Hughes as the “midwife” of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes noted that it was Fauset who published his first poems in The Crisis. Other figures which rose to prominence during the 1920s such as Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen and Claude McKay were given access to The Crisis which had broad circulation during the 1920s.

The Second Pan-African Congress organized by Du Bois was held in late August and early September of 1921 in the European capitals of London, Paris and Brussels. Fauset represented the NAACP at the gatherings and later wrote an extensive report in The Crisis entitled “Impressions of the Second Pan-African Congress” published in the November edition of the magazine. Following her detailed description of the Congress, “A Manifesto to the League of Nations” was reprinted.

The League of Nations, formed after the conclusion of the First Imperialist War and the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, agreed to accept the manifesto from the Pan-African Congress delegation as outlined by Fauset in her report. Nonetheless, the United States never joined the inter-governmental organization even though President Woodrow Wilson was given a Nobel Peace Prize for his participation in the post-war talks and the Treaty of Versailles.

Fauset’s interest in Pan-Africanism had begun before she joined The Crisis magazine in 1919. The first issue of the Journal of Negro History, founded by Dr. Carter G. Woodson in 1915-16, featured a book review by Fauset on the history of Haiti which was written by T.G. Steward. Prior to going to the Second Pan-African Congress, she co-authored an article with Cezar Pinto on the Brazilian abolitionist Jose Do Patrocinio who worked tirelessly for the liberation of Africans still enslaved in the South American state during the 1870s and 1880s. The article entitled “The Emancipator of Brazil” appeared in the March 1921 issue of The Crisis.

The literary editor and mentor traveled regularly to France to study at the University of Paris Sorbonne. She was fluent in French and other languages in which she taught in high schools before and after leaving The Crisis.

In 1925, Fauset visited Algeria, then a French colony in North Africa. She would write a two-part report published in The Crisis in their April-May 1925 editions entitled “Dark Algiers The White” where she recounts her experience in the living quarters of the colonized population. France occupied Algeria from 1830 to 1962 when a guerrilla war led by the National Liberation Front (FLN) forced the French government to grant independence to the country.

The Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s would come to a screeching halt when the stock market collapsed in October of 1929. The economic downturn disproportionately impacted African people leading to a new phase in the struggle to end racism and national oppression on an international scale.

The Great Depression, the Rise of Fascism and the Second Imperialist War

As the U.S. and the entire capitalist world fell into an unprecedented economic depression in the 1930s, resistance movements arose at a rapid pace. Efforts aimed at organizing labor unions and winning recognition from the corporations and later public entities accelerated.

In several European states the crisis had already taken hold in the years following World War I when inflation and unemployment reached astronomical levels. The Treaty of Versailles has often been cited as fueling the financial downfall in the 1920s and 1930s.

Italy, where a fascist government came to power in 1922 under Benito Mussolini, embodied aspirations to revive the ancient empire of Rome. In 1896 at the Battle of Adwa, the First Italo-Ethiopian War resulted in the defeat of the Kingdom of Italy in their campaign to expand its colonial holdings. Earlier in 1889, the Italians seized Eritrea and later signed the Treaty of Wuchale which supposedly protected Ethiopia from attack.

Nonetheless, the fascist Italian regime had no intentions of abiding by the treaty and seven years later attempted to seize control of Ethiopia. The defeat of Italy in 1896 is still commemorated every year in Ethiopia as an historic event which impacted the entire struggle against colonialism.

Nearly four decades later in October 1935, Mussolini’s army invaded Ethiopia again causing massive casualties. The use of mustard gas by the Italians and other atrocities prompted international outrage. In the U.S. and Britain, committees arose among African Americans and people of African descent living in England calling for the withdrawal of Italian forces.

Socialist and Pan-Africanist organizers C.L.R. James and George Padmore, both of whom were originally from Trinidad-Tobago, then living in the United Kingdom, formed the International Friends of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935-36. In the U.S., African Americans set up recruiting stations to send volunteers to fight against the fascists occupying Ethiopia.

The events of 1935 portended much for the future of Europe and the world. When Adolph Hitler and the Nazi Party took power in 1933 in Germany it signaled the imminent threat of fascism in Europe. By 1941, both Britain and the U.S. were brought into the war against the fascists and the imperial expansionist regime in Japan.

During the Second Imperialist War, heavy fighting took place in the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Eastern and Western Europe. Due to the imperialist character of the war, fierce battles were fought in the North African states of Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Libya. The Italians had fought against the anti-colonial resistance in Libya from 1911 to 1931. When the Italian army failed to defeat Britain in North Africa during the early 1940s, fascist Germany sent in their troops in a failed attempt to secure the region for the expansionist aims of Berlin and Rome.

By the conclusion of World War II, a reconfiguration of international power dynamics came into being. The U.S. would emerge as the undisputed dominant imperialist state while the Soviet Union not only reclaimed their territory from Nazi occupation during 1941-43, the Red Army drove the Nazis across Eastern Europe back into Germany where they met their inevitable defeat in May 1945.

After the conclusion of WWII, the struggle against colonialism, imperialism and racism accelerated. However, the emergence of an anti-capitalist bloc within the revolutions in Korea, Vietnam and China along with the rise of socialism in Eastern Europe, would pose a monumental challenge to the aims of the U.S. to consolidate hegemonic control over the globe.

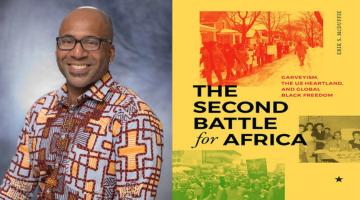

Abayomi Azikiwe is the Editor of Pan-African News Wire.