In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their books. This week’s featured author is Nessette Falu. Falu is an Assistant Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Her book is Unseen Flesh: Gynecology and Black Queer Worth-Making in Brazil.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

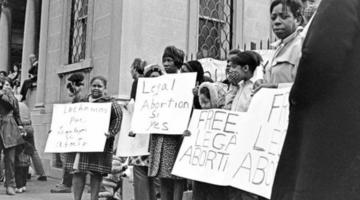

Nessette Falu: The book encourages BAR readers to become more attuned to how reproductive injustice is rooted in local and global political and social power. The U.S. shares with Brazil similar ideological systems and histories about how Black and Indigenous women’s bodies are controlled reproductively through issues such as sterilization, eugenics, abortion rights, maternal/birthing autonomy and birthing care. My book is an intimate examination of Black queer women’s experiences with racial, gender, and heteronormative abuse of power and privilege by gynecologists. The narratives and analyses in my book about the unseenness of the social conditions and traumas of Brazilian Black queer women in and out of healthcare move readers to understand how gynecology and medicine, broadly, is a microcosm of a larger social laboratory in the world.

If we accept that systemic violence pervasively interconnects all capitalist institutions such as military, prisons, judicial system, education, and food and land distribution, then we would understand that healthcare, specifically gynecology, is equally, if not more, invested in maintaining systems of power such as racism, heteronormativity, and class privilege. My book is not an indictment of gynecology and good physicians. However, gynecology is a site of making race, gender, sexuality, and class and the biological and social worlds are intertwined through medical hierarchies which rely upon the legal, corporate, and political spheres for advancements. That said, the local and global political wars to control women’s bodies are always directly linked to capitalist investments in healthcare, for better or worse, in the public and private sectors.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

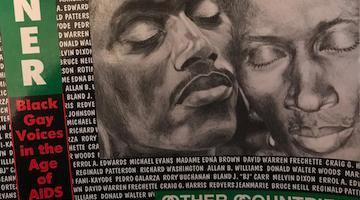

My book mostly speaks to reproductive justice movements in the Caribbean and Latin America but also in the U.S. and across the African Diaspora. I invite activists and community organizers in the RJ movement as well as other movements such as BLM and LGBTQI+ organizing, to become more entuned with how Black queer reproductive health is not given enough attention in healthcare and within social justice. I write about how Brazilian Black queer women experience anti-Blackness, heterosexism, sexism, classism, and other systems of violence all at once within medical spaces, such as gynecology, to raise awareness about how their traumas are silenced by the institutional logics that ordinarily dismiss these experiences. Activists and community organizers are reminded in my book that even RJ work is not disconnected from resisting, protesting, and abolishing different forms of structural violence. Medical racism, for example, is part of structural racism inasmuch as structural racism is also part of medical racism. In other words, structural violence of healthcare as experienced within interactions is part of a larger social laboratory beyond its walls. At the same time, health care and physicians’ socialities constitute structural power that produces structural violence within the world, particularly through racial capitalism and gender domination. This point is most evident, more generally and beyond the scope of my book, in the ways that Roe v Wade was overturned and defended by politicians and pro-life supporters. Of course, I do not discuss these U.S.-based issues in my book, which only focuses on Brazil. However, activists and community organizers would gain insight into how we ought to center the lives of Black queer people who are challenged by their gynecological experiences, and reproductive health broadly. We need an expansive way of doing and talking about RJ transnationally.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

I dismantle different ideological issues in the book. One concept steeped in medical practice and logics, which I discuss in Chapter 2, is the much-needed expansion of gynecological trauma, a medical term for pelvic injury via surgery or procedure, fall or personal injury, and sexual violence. I argue in this chapter that gynecological trauma encompasses varied traumas caused within gynecological spaces. These traumas are physical, emotional and psychological, and social. Through a term I coined, “gynotrauma,” I call attention to these forms of traumas that occur most often at once by healthcare providers and the system of healthcare. My research participants remember in deep negative emotional ways insults, aggressive pelvic exams, derogatory language, and insensitive experiences toward their sexualities, gender expressions, and specific pelvic exam needs. Gynotrauma is a concept by which we articulate the ways racism, heteronormativity, and gender and class violence operate within gynecology and causes layered trauma through the gynecological experience of the examination and consultation.

I also rethink the ways that prejudice is not just a bias and preformed idea. Instead, I situate in deeper ways how prejudice is a product of structural power and violence and manifests by intersecting within power relations anti-Blackness and racism, heterosexism and homophobia, sexism, classism, ableism, and ageism. My participants understand through lived experiences and witnessing structural injustices impacting Brazilian Black communities that preconceito, or prejudice, is a way to channel and enact anti-Blackness. They know when they are targeted as Black female bodies with degradation or barely being touched during an examination. They also differentiate how anti-Blackness only allows for their sexual identities and gender expressions to further provoke discrimination, neglect, or mistreatment against their Black bodies. The intensity of being othered at multiple levels within these spaces is most evident within their affectively traumatic experiences.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

I am most inspired by the intellectual movements in Brazil historically led by Brazilian Black feminists. In my book, I write about the intellectual ideas and impact that Brazilian Black feminists offer us in transnational ways. Brazilian Black feminist, activist, politician, professor, and anthropologist Lélia Gonzalez (1935-1994) is one of my biggest inspirations for my work. Lélia Gonzalez left a legacy of intellectual writings that challenged the transnational feminist movements to take seriously that Black and Indigenous people are the main fiber of Latin American sociopolitical life. She coined the term, “Améfrica Ladina,” to expand a conversation that centers these racial and ethnic identities and lived experiences. Her discourses have left a political and cultural mark on the ways that Black feminist transnationally collaborate across the Americas, Caribbean, and Africa. Her intellectual and political work was fundamental to the shaping of Brazilian Black women’s movement that fought against racism, sexism, and class injustices. Lélia Gonzalez was a force to reckon with for facilitating more racial solidarity across various movements across the Americas. She is a true legendary of Black feminist thought and praxes in Brazil.

I am also deeply inspired by Brazilian Black feminist activist, professor, and intellectual Sueli Carneiro. Much like Lélia Gonzalez, Sueli Carneiro has published extensively about how to mobilize social justice against racism, sexism, classism, and heteronormative systems of power. She coined the term, “enegrecer” which refers to blackening the feminist movement that does not center and act on behalf of Black women. Through her intellectual work that interrogates many topics from poverty, health and healthcare, police violence, domestic work, and education, she inspired me to understand how race, gender, and class intersect in Brazilian state-sanctioned violence and in the policies and political structures that undermine the lives of Brazilian Black men and women. Sueli Carneiro continues to impact transnationally shape Black feminist thought today.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

I highly recommend two books that inspire my work and public practice. Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth (2019) by Dána-Ain Davis. Davis is a Black feminist anthropologist and doula. She has deepened our understanding of what she terms, “obstetric racism,” by analyzing how medical racism is pervasive in obstetric care and contributes to high morbidity and mortality of both Black pregnant women and premature Black babies. Davis also takes a deep dive into the sociohistorical implications of medical knowledge and perception of Black premature babies in the U.S.

Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (2017) by historian Deirdre Cooper Owens is a must-read. Cooper Owens examines many layered aspects of the history of gynecology during the nineteenth century including medical journals and various archives to expose the violently hidden ways that the professionalization of gynecology capitalized and abused enslaved Black women. In Medical Bondage, Cooper Owens coins the term, “superbodies,” to frame the ways that enslaved Black women were human vehicles for establishing medical knowledge and practice. The author also reveals through many medical narratives detailed features of enslaved Black women’s suffering during these medical and social processes of slavery and shows us how race, gender, and sexuality were deployed to shape the field of gynecology today.

These two books continue to influence my future work and second book on sexual violence in medicine in the U.S., particularly to understand the ways that the sociohistorical legacy of medicine, slavery, and violence is institutionalized in healthcare today.

Roberto Sirvent is the editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.