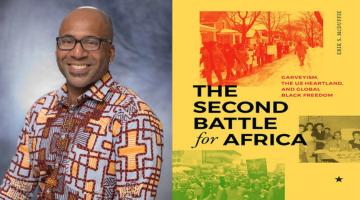

Black Citizenship Forum: Pan-Africanism and the Pitfalls of National Citizenship / Photo: Dr. Layla Brown-Vincent

The Review interrogates the thought of academic and activist Layla Brown-Vincent, who says she was “reared and steeped in Pan-Africanist thought and organization” from birth.

For the second post in the Black Citizenship Forum we feature an interview with cultural anthropologist Dr. Layla Brown-Vincent. Brown-Vincent teaches Africana Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. She is completing a manuscript titled Return to the Source: The Dialectics of 21st Century Pan-African Liberation that compares the political strategies of the Movement for Black Lives with those of La Red de Organizaciones Afrovenezolanas (the Afro-Venezuelan Network). For The Black Agenda Review, Brown-Vincent responded directly to the series of questions we sent to contributors for the Forum. Her responses focus on the possibilities of a return to the philosophy and political practice of Pan-Africanism as a model for resolving the limits of Black citizenship and she offers Venezuela as an example of an alternative vision of citizenship for people of African descent.

From your location, what do you see as the primary and most urgent issues concerning Black people’s relation to the nation-state? How does Black people’s relation to the nation-state shape the experience and conditions of Black citizenship?

As a Pan-Africanist, reared in the intellectual traditions of the All African People's Revolutionary Party - GC, I follow the ideological teachings of Kwame Osagefayo Nkrumah, Sekou Toure, and Kwame Ture. They promote the fundamental political objective of a United States of Africa under Scientific Socialism. That Black/African people—whether located on the African continent or in the African diaspora—continue to seek belonging in a supra-national political community, however imagined, is a testament to the limiting and contentious relationship they have to their supposed national citizenship.

If I were to limit my answer to this question to Black/African people’s relationship with the U.S. nation-state, particularly in the wake of this past summer’s global uprisings and the most recent national elections, I would have to say that the masses of Black/African peoples continue to experience second-class citizenship—or 21st century slavery, as Malcolm X might characterize it. If we understand citizenship as full and equal membership in a given polity, we can clearly see that the Black/African masses do not exist on full and equal footing with the non-Black/African masses in this country. I find the US political system to be fundamentally undemocratic, corrupt, and morally bankrupt, and therefore do not personally view voting in the U.S. context as a worthwhile endeavor. However, if voting is a right supposedly guaranteed to U.S. citizens, the miseducation, voter intimidation, and voter suppression in this most recent election alone reveals the bankruptcy of Black/African citizenship in the United States.

“I find the US political system to be fundamentally undemocratic, corrupt, and morally bankrupt.”

I am also not sure that we, as Black/African peoples in the United States, can have a robust, imaginative, and ethical conversation about the state of our citizenship without being in dialogue with the Indigenous peoples of this land. I think that far too often we are seduced by ideas like the so-called “Black Belt Thesis,” as well as those assertions of a fundamental claim or right to citizenship in the US. I would never deny the forced role we had in building this country, a role which certainly entitles us to the same rights as our white settler-colonial counterparts. However, we need to make a continuous and vigorous political commitment to having this conversation about Black citizenship in the US with our Indigenous siblings. If we do not, we risk becoming complicit in perpetuating the same ills upon Indigenous peoples that white settlers have perpetuated for nearly five hundred years.

Historically, class has been a constitutive part of Black citizenship formation. Yet class has often held a difficult place in discussions of race and racism. What is your sense of how class conflict—especially the intra-racial class conflicts between the Black working classes and the Black middle classes and petit-bourgeoisie—has emerged where you are? Furthermore, is there an international dimension to this conflict, in as much as imperialism, multinational corporations, and transnational finance are remaking the local terrain of class, class conflict, and class struggle?

In a 1989 speech at the University of Chicago on lessons learned from the sixties, Kwame Ture declared that, “the class struggle in the African revolution must be more ruthless and uncompromising than in any other revolution.” He goes on to proclaim that “The African bourgeoisie is the most corrupt bourgeoise in the world. In Africa they seek luxury in the midst of mass suffering… In America as soon as they arrive at a position based on the blood of the people, they snatch that position and run away from the people.” Such an example can be seen in the likes of Clarence Thomas, Condoleezza Rice, Jim Clyburn, and even (or perhaps especially) Barack and Michelle Obama. These are enemies of our people, first and foremost, because their very existence is meant to quell our righteous discontent as a people. Furthermore, the active role they play in the public admonition of our very human responses to our inhumane existence is a betrayal par excellence. They only represent their opportunistic selves, using the masses of our people every step of the way. Ture concluded his speech with this admonition: “Here then the masses must come without pity and without mercy to trample upon these reactionary pigs who, after the people have gained struggle through their blood, come to hand back the gains on a silver platter to the very enemy the people fought.” Figures like Donald Trump are easy enemies because they make no bones about their priorities and objectives. The true danger for us as Black/Africans living in the United States lies with those who would have us believe they are working on our behalf in order to silence us.

What impact does U.S. imperialism have on Black citizenship? Do you see the possibilities for, or practices of, transnational or diasporic Black solidarity against empire?

When it comes to the question of US imperialism, I am inspired by the example of Venezuela. In November 2019, I participated in the First International Congress of Afro-Descendant People held in Caracas. The theme of the three-day conference was “Cimarronaje against Imperialismo”— Maroons Against Imperialism. It was organized by the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, or PSUV) and a number of organizations representing the Afro-Venezuelan community. The conference demonstrated Venezuela’s commitment to building political power and revolutionary solidarity among the globally dispossessed peoples of the African Diaspora.

The aim of the congress was to examine, “Afro-descendants in the programmatic agendas of social movements and left-wing political parties, within the framework of the International Decade for People of African Descent and Reparations, as a fundamental basis for the eradication of structural racism, a condition for the construction of Socialism.” For three days, approximately 250 delegates—including Roland Lumumba, the son of the late Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba—from more than 50 countries gathered in Caracas, Venezuela. Congress participants were divided into various tracks representing different social movements and tendencies, ranging from Pan-Africanism to Black feminism to multiple forms of Marxism. Each track had a specific set of agreed upon aims to structure its thematic workshops. Some of those aims included:

* To compile, configure and disseminate our own horizons of senses expressed in the liberating praxis of cimarrones and cimarronas of all times, through the construction of historical routes resulting in educational materials.

* To locate reparations not only in the economic and legal field but also taking into account reparations to epistemicides, culturicides, memoricides, linguicides, ecocides, filicides and economicides, through militant processes of literacy against colonization and imperialism.

* To recover decolonial, American, African and Afrodiasporic thought in general, which positions our places of enunciation in the consciences, incorporating them in the plans and study programs of all the educational subsystems and in the generators of media content.

* To systematize the recovery of the nodal nucleus of our Afro and diasporic narratives from international research groups and political, religious, spiritual and cultural platforms, impacting the communication structures and the public policies.

The congress concluded with a presentation of the final declaration of the congress to President Nicolas Maduro at Miraflores (the presidential house), to which all congress participants were invited. The final declaration included statements of solidarity with the peoples of Bolivia, Haiti, Colombia, Ecuador, an Chile, support for the legal recognition of Mexico’s afro-descended populations, condemnations of US and western European imperialist intervention around the globe and of US human rights violations of Black Americans and Black immigrants, and a call for recognition of and reparations for the genocide visited upon the children of Africa in the Americas. The congress concluded with a commitment from President Maduro to provide resources and to create a central operation point for Afro-descendant peoples working to build a global left movement guided by the political and material necessities of the oppressed masses. The resolutions placed a particular emphasis on the role of women, afro-descended and Indigenous peoples, and those ravaged by the world capitalist system.

“The final declaration included a call for recognition of and reparations for the genocide visited upon the children of Africa in the Americas.”

In January 2020, as a follow-up effort to continue growing, activists organized the International Anti-Imperialist Cumbe of Afro-Descended and African People to attend the World Conference Against Imperialism, which also took place in Caracas. The word “Cumbe'' comes from the Venezuelan maroon community Cumbe de Ocoyta (1768-1771), led by Afro-Venezuelan cimarron Guillermo Ribas. At this conference, the Cumbe redoubled its efforts by expanding the South-South International Center for Training and Research on Afrodescendant and African peoples.

I choose to read these configurations as an alternative visioning of belonging that moves beyond the nation state, even Venezuela, but that draws on the hemispheric visions of Simon Bolivar and Jose Marti that inspired the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez. That imagined belonging is precisely what took me to Venezuela for the first time in 2011, when I began conducting research for my dissertation. In many ways Venezuela in the early 2000s offered the hope of other possibilities for political community and belonging in much the same way Cuba did for previous generations of Black radicals. I imagine the South-South Center as a space of cross fertilization away from the spying eyes of the US government—a place that might birth a new generation of Black radicals that will facilitate more just and humane configurations of community and belonging.

As Joseph Biden takes office of the U.S. presidency, and we are presumably freed from the fascist terrorism of Donald Trump, alternative forms of Black belonging and citizenship become ever more important. While Biden may provide more structure in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and nominal economic relief on the domestic front, he has already made it clear that international policy will remain business as usual. Biden’s incoming Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, has confirmed that the new administration will continue to recognize Juan Guaido as the country’s “legitimate leader” despite the results of the last presidential election which clearly indicate Nicolas Maduro is the duly elected and constitutionally approved president of Venezuela. Biden even went so far as to invite Carlos Vecchio, one of Guaido’s cronies, who has assisted in coup attempts against Maduro, to his inauguration. Perhaps most importantly, Blinken also confirmed that Biden has no intent of removing, or even lessening the sanctions, which are effectively starving and killing hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans. If the US cannot respect the Venezuelan peoples’ electoral process and their right to sovereignty through the so called basic democratic right of electoral choice, what would make Black people in the US believe we have any chance of being recognized as rights bearing citizens?

What is the role of Black intellectuals—be they academics, activists, or artists—in helping to shape a public discussion around citizenship and national formation? Are you able to draw on a local history or tradition of Black intellectual activity that helps us make sense of the present?

In Consciencism, Nkrumah, describes his experiences studying in the United States. While studying philosophy at Lincoln University, Nkrumah recounts his encounters with Plato, Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx and others. One of the first arguments he makes in Consciencismis that, despite the temptations of seemingly universalist thought of such European philosophers and theorists, Nkrumah learned to “see philosophical systems in the context of the social milieu which produced them.” Heeding his own call, Nkrumah resolved that the first necessary step in the process of our liberation as Black/African people is “a body of connected thought which will determine the general nature of our action in unifying the society which we have inherited, this unification to take account, at all times, of the elevated ideals underlying the traditional African society.” Social revolution, he continues, must have “standing firmly behind it, an intellectual revolution, a revolution in which our thinking and philosophy are directed toward the redemption of our society. Our philosophy must find its weapons in the environment and living conditions of the African people.”

From birth, I was reared and steeped in these teachings, this tradition of Pan-Africanist thought and organization. These teachings are so embedded in me that I often have to be careful to give credit to the likes of the names I mention here as opposed to my own parents. It is from these teachings and my upbringing, as a child of members/organizers with the All African People’s Revolutionary Party-GC, that I draw my own purpose, make sense of the present, and endeavor to determine the contribution I am to make before I exit this world.

My position on the role of intellectuals can be summed up with a quote from the Kwame Ture speech I mentioned earlier:

“No individual African...makes any advance unless it is a result of mass struggle. Any student sitting in any seat in any college in America knows that they didn’t gain that seat through any individual talents but only through the struggles of the masses of their people. Thus that seat belongs to the people, the knowledge they acquire there must be used for the people. Otherwise they have already betrayed the people and have repeated errors... Students have a responsibility to use their knowledge to help advance the struggles of humanity.”

Editors, The Black Agenda Review

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com