Postal workers strike in March 1970. (ANTHONY CAMERANO/AP PHOTO)

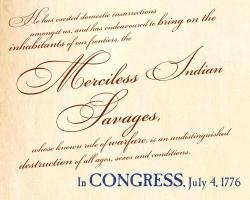

The 4th of July celebration is a relic of American exceptionalist ideology. There is very little independence in a capitalist dictatorship.

Here’s a little Fourth of July Critical Race and Labor History for you: On July 2, 1777, Vermont became the first colony to abolish slavery when it ratified its first constitution and became a sovereign country, a status it maintained until its admittance to the union in 1791 as the 14th state in the United States. However, Harvey Amani Whitfield, author of The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810, writes that slavery in Vermont was gradually phased out over a period of multiple decades. Additionally, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) staff write in “Vermont 1777: Early Steps Against Slavery” that even though “Vermont, Rhode Island and Connecticut abolitionists achieved laudable goals, each state created legal strictures making it difficult for ‘free’ blacks to find work, own property or even remain in the state” and that Vermont’s 1777 constitution’s “wording was vague enough to let Vermont’s already-established slavery practices continue.”

Even when slavery was finally outlawed in the Northern states, their economies were fully intertwined with the institution of slavery, with every occupation and institution from barrel makers to bankers to insurance companies to the textile industry and many more dependent on slavery. The authors of Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery describe how New York City mayor Fernando Wood pushed for his city’s secession from the Union during the Civil War because “the lifeblood of New York City’s economy was cotton, the product most closely identified with the South and its defining system of labor: the slavery of millions of people of African descent.”

Sounds like the case for reparations was made when northern capitalists were found to have depended on the enslavement of our ancestors as much as the southern capitalists did.

On July 2, 1839, Joseph Cinqué led fifty-two fellow captive Africans, recently abducted from the British protectorate of Sierra Leone by Portuguese slave traders, in a revolt aboard the Spanish schooner Amistad. The ship departed from Havana, Cuba with the 53 Africans who had been purchased by two Spanish plantation owners and were being shipped to be enslaved on a plantation in the Caribbean. The Africans seized the ship, killed the captain and the cook, but spared the ship’s navigator’s life in order to direct the ship back to western Africa, but he instead steered it north until it was discovered off the coast of Long Island, New York, and was hauled into New London, Connecticut by the U.S. Navy.

President Martin Van Buren, who wanted to win pro-slavery votes in his upcoming bid for reelection, wanted the prisoners returned to Spanish authorities in Cuba to stand trial for mutiny. A Connecticut judge, however, issued a ruling recognizing the defendants’ rights as free citizens and ordering the U.S. government to escort them back to Africa, which of course the U.S. government didn’t want to do and appealed the case to the Supreme Court. Former president John Quincy Adams represented the Amistad Africans in that case, and Joseph Cinque testified on his own behalf, winning the freedom of the Amistad Africans.

In Assata: An Autobiography, Assata Shakur says, “Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them.” As much as the Africans aboard the Amistad were able to argue to the US Supreme Court for their freedom, their victory was not extended via legal precedent or even under the auspices of Adams’ argument that it was the Africans who should be treated sympathetically because they were free people illegally enslaved who were “were entitled to all the kindness and good offices due from a humane and Christian nation,” rather than the Spanish in Cuba. Because slavery was legal in the US, the same “kindness and good offices from a humane and Christian nation” were not extended to Africans held in bondage on these shores. Rather, the end of the institution of slavery and freedom for all Africans in the US would not come for another 26 years with the end of the Civil War.

Africans in the US could not - and cannot - appeal to the moral sense of our oppressors to grant us freedom because they have none, and our freedom was not and is not theirs to give us, but it is ours to wrest from their immoral denials of it.

On July 3, 1835, 2,000 workers, mostly children, went on strike from 20 textile mills in Paterson, New Jersey to demand better work hours. The mostly child workers had previously been forced to work 13 hours per day Monday through Saturday, and were regularly fined for minor disciplinary infractions. Although the strike was eventually broken, the companies decreased workers’ hours to twelve hours during the week and nine hours on Saturday, which isn’t much of an improvement.

Fast forward to 2022, when New Hampshire and New Jersey passed laws extending the hours teenagers could work. New Hampshire lowered the age of teens able to bus tables where alcohol is served from 15 to 14 years old. Minnesota is considering a proposal to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to work on construction sites, and one in Iowa would allow 14-year-olds to work in meat coolers. Are we going to see children once again on the front lines of workers’ strikes in the US in the 21st century?

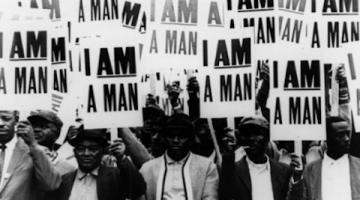

And on July 3, 1919, active members of the Army’s segregated 10th Cavalry Regiment (“Buffalo Soldiers”) were in Bisbee, Arizona, to participate in the town’s Independence Day parade. In the early 20th century, Bisbee was a mining town in which Mexican, Chinese, and African American laboring communities were discriminated against. It was a “sundown town” for Chinese Americans and Black laborers had limited employment options.

According to a New York Times account, local white law enforcement “planned deliberately to aggravate the Negro troops so that they would furnish an excuse for police and deputy sheriffs to shoot them down.” The chief of police and his men began moving through town, systematically disarming Black soldiers by force. Hundreds of shots were fired at the Black cavalrymen by the police and by civilian white vigilantes. Those servicemen who had not yet been disarmed of course defended themselves and returned fire. Some of the cavalrymen were wounded, but no one was killed, which leads me to believe that the cavalrymen may have intentionally missed their targets. But that’s just conjecture on my part.

What is not conjecture is that African American soldiers who fought a war for the freedom of others overseas were not free from racist police terrorism and white supremacist vigilante violence upon returning to the US, and had to fight to march in a parade that celebrated independence in 1776 that was not extended to their ancestors in bondage. Even after all the state-sanctioned violence committed against them, the 10th Cavalry Regiment joined the Fourth of July parade in Bisbee, Arizona the following day.

Fast forward to today, when the Supreme Court has banned colleges and universities from using race as one of the factors in admissions decisions, except for military academies which are exempt from their ruling. I will discuss this ruling and the long right-wing road to the dismantling of affirmative action in higher education in an upcoming article, but in the meantime, Rep. Jason Crow (D-Colo.), a former Army Ranger, wrote of the SCOTUS decision on Twitter: “This decision is deeply upsetting but outright grotesque for exempting military academies. The court is saying diversity shouldn’t matter, EXCEPT when deciding who can fight and die for our country—reinforcing the notion that these communities can sacrifice for America but not be full participants in every other way.”

If we knew our history, we’d know that this sentiment is not just a notion as Rep. Crow describes it, but a historical fact as one of the major impetuses of the widespread racist terrorism and violence against Black people during the Red Summer of 1919 was white response to Black soldiers returning from WWI believing that their service in war for this country abroad meant they were equal citizens in this country. White supremacists with badges and without, brutalized and murdered Black soldiers and civilians across the country who dared believe such a thing.

Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo who was born on July 2, 1925 and who was assassinated by the US and Belgian governments in 1961, said, “Without dignity, there is no liberty, without justice there is no dignity, and without independence, there are no free men.”

One might argue that we have a measure of independence in this country. But without justice and dignity, it’s hard to see how most of the working class and poor can celebrate liberty that we don’t really have. And until we all have dignity, justice, and liberty, we are not really free.

So what, to the exploited working class and poor in a capitalist dictatorship, is the Fourth of July?

Jacqueline Luqman is a radical activist based in Washington, D.C.; as well as co-founder of Luqman Nation, an independent Black media outlet that can be found on YouTube (hereand hereand on Facebook; and co-host of Radio Sputnik’s “By Any Means Necessary”.