Theorists of racial capitalism are not interested in the characteristics capitalism could have had in some imagined world, but in the world as it exists.

“The point of theorizing about racial capitalism is to focus our attention on the broader forms of organization that are constitutive of social life under capitalism, beyond how it organizes work and production.”

In a recent article for Dissent, editor emeritus Michael Walzer wonders aloud what “racial capitalism” means. Its conclusion stops graciously short of calling for a ban of the term, but does suggest that “the phrase should always be queried by the editors,” since he has failed to pin down a satisfactory definition of the term.

But why was Walzer spitballing about what “racial capitalism” means in the first place? He could have just asked.

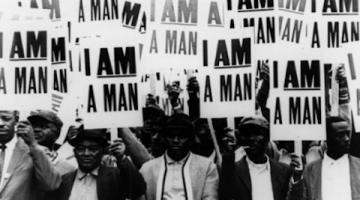

The theory of racial capitalism concerns a set of intellectual positions about our global social structure that developed over the twentieth century. Eric Williams’s 1944 classic Capitalism and Slavery argued for what economic historians now know as the “Williams thesis”: roughly, that the trans-Atlantic slave trade caused the development of both global racism and capitalism. In the 1950s, his fellow Trinidadian, the sociologist Oliver C. Cox, developed some of the key building blocks of what became the “racial capitalism” theory in the books Class, Caste, and Race and The Foundations of Capitalism, in which he compared and contrasted the social structures found on the Indian subcontinent with those of pre-capitalist Europe. Among his many conclusions: that “racial antagonism . . . developed within the capitalist system as one of its fundamental traits.”

“The trans-Atlantic slave trade caused the development of both global racism and capitalism.”

African-American political theorist Cedric Robinson followed up on this work in Black Marxism, a text which thoroughly criticized Marx and Marxists for inattention and marginalization of non-Europeans. Robinson’s book is often credited as the origin of the term “racial capitalism” to refer to the way of understanding the general history of global capitalism developed by himself and these thinkers. African-American geographer and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore, one of today’s leading theorists of racial capitalism, built on this further, famously defining racism as the “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” Racism so understood, she argues, has been important for regimes struggling to maintain themselves amidst political and economic crises, thereby giving racism a functional role in the production and reproduction of capitalism itself.

The thought that unites these theorists is that the European colonial conquests beginning in 1492 spread both the economic linkages that would congeal into capitalism and the forms of social organization that would become races. For Robinson, an important reason why these two phenomena are connected is that Europe, the region of the world that produced the world system-constituting empires, was already racially organized. He argues that the forms of conquest, dispossession, and labor exploitation that would be visited on Native Americans and Africans, as well as the ideologies that justified this subjugation, had already been run on a smaller scale on Slavs and the Irish. There was thus not two separate acts of creation, but one and the same act of spreading European social forms that left us with capitalism and racism.

“Europe was already racially organized.”

With all of this context in mind, it’s easy to see why Walzer’s discussion of racial capitalism is off. He begins by ascribing a motive to the term itself, saying: that “[r]acial capitalism is one kind of capitalism, and then there must be other kinds” and that “[t]he point of the adjective, then, is simply to focus our attention, for good reasons, on non-white workers.” Walzer is wrong on both counts—if Cox, Robinson, Williams, and Gilmore are right, then racial capitalism is the only sort we’ve ever had. The point of the adjective is to focus our attention on the broader forms of social organization that are constitutive of social life under capitalism, beyond how it organizes work and production.

Walzer then asks whether exploited workers in 1844 Manchester were participating in a (racially) capitalist system, since these workers were white. He flirts with the beginnings of the right answer—acknowledging that the cotton they processed was cultivated by slave labor—but insists that the “key issue is exploitation, not racism.” After all, Walzer says, capitalism would still have emerged if Blacks had not been targeted for the slave trade—it would simply have exploited Irish workers instead.

Now, for the record, this is probably false in the most straightforward sense: in total, the trans-Atlantic slave trade is estimated to have trafficked over 12 million Africans over the centuries (for a sense of scale, the entire population of Ireland in the seventeenth century was less than 2 million).

“Walzer insists that the ‘key issue is exploitation, not racism.’”

But, more importantly, this point just doesn’t matter. The role of necessity and counterfactuals in Walzer’s argument involves a confusion about the activity theorists of racial capitalism are engaged in. Suppose we were trying to work out why a building retains as much heat as it does. Among the things we would want to know are what the building is made of, and how its various elements are arranged. It would not be relevant that the architects could have made different decisions in placing rooms, or that different materials could have been selected.

In just the same way, theorists of racial capitalism are not interested in the characteristics capitalism could have had in some conceivable world. They describe it based on the features it does, in fact, have—whether those features are contingent on the idiosyncrasies of the particular people or processes that produced it or they are counterfactually robust. In either case, they are equally of interest to the theorist of racial capitalism. As such, the genre of response that Walzer rehearses here addresses different questions than the ones theorists of racial capitalism are trying to answer.

Of course, all this theorizing is not just to describe the world but also to assist in changing it. And here one might think that counterfactuals are relevant: one hypothetically could design an exploitative system of production and work that was not organized around racism, or a feudal system wherein all the gentry are white and all the serfs are Black. But the point of theorizing about racial capitalism is the contention that the actual system we struggle against is not like either of these hypotheticals, but is a system in which race and capitalism are mutually supporting.

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, where he focuses on social/political philosophy and ethics. He is also a member of Pan-African Community Action and an organizer of the Undercommons.

Liam Kofi Bright is an assistant professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Read Michael Walzer’s original article and his reply to Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and Liam Kofi Bright.

This article previously appeared in Dissent Magazine. BAR editors changed the title.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com