A man sets up a tent in front of police during a 2021 protest in Los Angeles, ahead of a cleanup of the encampment. (Ringo Chiu/AFP via Getty Images)

The Supreme Court will soon decide if unhoused people can be issued jail time or fines for sleeping on the streets. Black people experiencing homelessness would be disproportionately impacted.

Originally published in Capital B News.

As America’s affordable housing crisis grows, especially for those of retirement age, Black folks continue to be pushed into homelessness at a disproportionate rate.

Advocates argue that an upcoming U.S. Supreme Court ruling may make it even more dire.

Earlier this month, the court announced that it would hear a case that will essentially decide if people experiencing homelessness can be issued jail time, tickets, and fines for sleeping on the streets — even if there are no shelter alternatives available for them. The case will be heard either this spring or in the fall.

While this case formally applies to Western states, including California, experts believe the ruling will have national implications. In recent years, at least half a dozen Republican-led states have pushed for anti-homeless bills. These bills have proposed to penalize cities that allow tent encampments and to divert funding from these cities meant to be used for supportive housing options.

If instituted, those experiencing homelessness believe the practice will only make it harder for Black Americans to dig themselves out of poverty.

“Many people who are housed, Republican — or no matter what party they are — are clueless about the realities of houselessness,” said Theo Henderson, a 50-year-old man who experienced homelessness in Los Angeles for nearly a decade.

“They believe that in large part that it is a personal failure, and in doing so, they believe that houselessness should be punished just like burglary or theft.”

Henderson was a schoolteacher in L.A., but after losing his job and accruing thousands in medical debt related to his diabetes, he was evicted from his apartment in 2013. He sat on a waiting list for subsidized housing for years.

Like Henderson, 1 in 6 Black Americans over the age of 50 have already experienced homelessness. By the end of this decade, across all races, homelessness among older adults is expected to nearly triple as housing prices and rents continue to rise.

Henderson believes that if the ruling allows widespread anti-homeless laws to be enacted, cities are going to see “a lot more squatting or a lot more unhoused people using creative solutions to hide from society and away from the possibility of criminalization.”

“Even if it is not always enforced, there’s going to be a lot of people that are going to be in very difficult, precarious situations, and they’re going to have to take penitentiary chances,” he added.

“A generation-altering moment”

The case, which is seen as the most significant challenge to the rights of unhoused people in two generations, comes as the focus on public displays of homelessness, like tent encampments, has intensified and become a significant focus in elections across the country. Last year, the national homelessness count reached 580,000 people as affordable housing options and government-funded support options continued to dwindle.

Marques Vestal, assistant professor of urban planning and critical Black urbanism at the University of California, Los Angeles, believes the court will ultimately decide to allow cities to enforce anti-homeless laws because of its documented right-wing shift and how the “polarizing” approach to addressing homelessness has separated Democrats and Republicans.

“It will be a generation-altering moment in urban history where cities are going to be able to enforce constitutional removal and displacement,” said Vestal, who has researched how policing, fines, and fees have contributed to the Black homelessness crisis in Los Angeles.

“We’re supposed to put people from encampments into either temporary or permanent housing. Instead, we’ll lose most of those people,” he adds. “This will lead to a new regime of debt, and for Black folks, debt is always some kind of leverage for some other burying harm.”

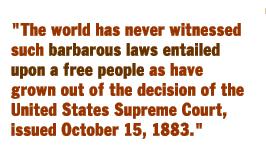

The case is a challenge to a 2018 class-action lawsuit brought by three people experiencing homelessness in Oregon who claimed the city they lived in punished them for being unhoused. The city of Grants Pass, Oregon, argued that the unhoused people could just leave and go elsewhere, but the state Supreme Court ruled in favor of the unhoused plaintiffs.

The decision reaffirmed another 2018 case that said people without housing couldn’t be punished for sleeping outside on public property if there weren’t adequate shelter and affordable housing options available. In the years since, this case has shaped how Western cities, where two-fifths of people experiencing homelessness live, respond to the crisis.

However, some groups in favor of enforcing these laws say it is about more than just punishment or throwing people in jail. The California State Sheriffs’ Association and the California Police Chiefs Association say “they, by no means, argue for the criminalization of the homeless” and are working toward “improving the outcomes” for unhoused people.

But for those who’ve experienced homelessness, the fear remains.

In Los Angeles, the city’s police department receives one call every four minutes related to homelessness. Since 2020, the city has ramped up its focus on removing tent encampments. A recent survey found that in Los Angeles, the same amount of unhoused people receive police citations for sleeping on the streets as they do any kind of housing, whether temporary or permanent.

“The people and organizations that are pushing for these kinds of carceral solutions are going to really put the feet to the fire of the police officers to do this kind of hostile enforcement,” said Henderson, host of the We the Unhoused podcast.

“It’s inhumane,” said Ryan Johnson, an unhoused man who has experienced chronic homelessness for three years in five different states. “It reminds me of a poor tax, like overdraft fees. That only affects the people that are trying and trying to have their shit together but never get the support.”

Johnson has lived on the streets of New Orleans for roughly a year. He knows a handful of people who’ve received supportive housing options from the city, but he has yet to receive any.

The “largest driver of the racial wealth gap”

While much of the national focus on homelessness has centered around the growing drug and overdose crisis, data shows, especially for Black unhoused people, it is an issue of affordability.

Black Americans are the most likely racial group to be renters, as rental prices nationwide have grown nearly 30% higher than inflation since 2000. As a result, Black people face the greatest burden to access housing and have the highest rate of evictions nationwide.

A recent study even found that nationwide, Black people face the highest upfront rental costs, paying on average $150 more in security deposits than white people and $15 more in rental application fees.

Adam Mahoney is the climate and environment reporter at Capital B. Twitter @AdamLMahoney