As the world watches the ongoing genocide in Gaza, a thorough reading and understanding of Frantz Fanon's writings around colonialism, revolution, and psychology are critical to the struggle for Palestinian liberation, and liberation for us all.

Originally published in Africa is a Country.

For Europe, for ourselves, and for humanity … we must work out new concepts and try to set afoot a new man.

— Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

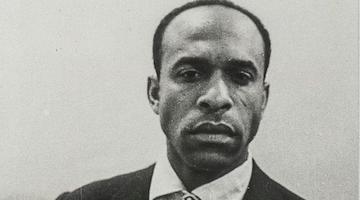

Frantz Fanon’s dynamic and revolutionary thinking, always centered on creation, movement and becoming, remains utterly prophetic, vivid, inspiring, analytically sharp and morally committed to disalienation and emancipation from all forms of oppression. Fanon strongly and compellingly argued for a path to a future where humanity “advances a step further” and breaks away from the world of colonialism and the mold of European “universalism”. He represented the maturing of the anti-colonial consciousness and was a decolonial thinker par excellence. As a true embodiment of l’intellectuel engagé, he transformed the debates on race, colonialism, imperialism, otherness, and what it means for one human being to oppress another.

Despite his short life (he died from leukemia at the age of 36), Fanon’s thought is very rich and his work prolific, ranging from books and scientific papers to journalism and speeches. He wrote his first book, Black Skin, White Masks, two years before the battle of Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam (1954), and his last book, the famous The Wretched of the Earth, a canonical work about the anti-colonialist and Third Worldist struggle, one year before Algerian independence (1962), during the period of African decolonization. In his trajectory and across his work we can see interactions between Black America and Africa, between the intellectual and the militant, between thought/theory and action/practice, between idealism and pragmatism, between individual analysis and collective movements, between the psychological life (he trained as a psychiatrist) and the physical struggle, between nationalism and Pan-Africanism, and finally between questions of colonialism and questions of neocolonialism.

It is neither a surprise nor a coincidence that we are witnessing a renewed interest in Fanon and his ideas since the October 7 Hamas attacks on the Zionist entity and occupying settler colony of Israel and the ensuing genocide against the Palestinians. Without any doubt, his analysis and thinking remain highly relevant and enlightening, due to the endurance of coloniality (which he analyzed) in its myriad forms, from settler colonialism in Palestine to neocolonialism in various parts of the global South. However, some of this renewed interest—particularly in relation to the situation in Palestine—succumbs to simplistic critiques and erroneous and insidious readings of his work that tend to distort it and to disconnect it from his anti-colonial and revolutionary praxis, as well as from his unwavering commitment to the liberation of the “wretched of the earth.” These supposedly “critical” endeavors cannot be dissociated from the broader attacks on Palestinians’ right to resist colonialism using any means necessary and the disdainful attitude toward people who show uncompromising solidarity with their resistance and liberation struggle. In some cases, the whole enterprise amounts to racism masquerading as intellectual discourse.

This is not new: there exist many reductive interpretations of Fanon, interpretations that eliminate either the historical/political dimension or the philosophical/psychological dimension of his work, depending on the social imperatives of the moment. Fanon was a political thinker, a revolutionary militant, and a psychiatrist, and all of these aspects of his life formed a coherent unity: dialectical, complementary, and enriching each other. After all, his was a project of combating alienation in all its forms: social, cultural, political and psychological. Fanon lived the life of a revolutionary, an ambassador, and a journalist, but it is impossible to separate these many lives from his scientific and clinical practice. Similarly, his expressions and articulations were not only those of a psychiatric doctor, but also those of a philosopher, a psychologist and a sociologist. Fanon was a pioneer precisely because he combined a commitment to social transformation with a commitment to the psychological liberation of individuals. His essential aim was to think about, and construct freedom as disalienation, taking place within a necessarily historical and political process.

Fanon, the revolutionary psychiatrist

Science depoliticized, science in the service of man, is often non-existent in the colonies.

— Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism

Arriving at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria in 1953, Fanon realized quickly that colonization, in its essence, was a major producer of madness, hence the need for psychiatric hospitals in colonized countries. He enthusiastically undertook to revolutionize mainstream psychiatric practice, in accordance with the “desalienist” teaching of the Saint-Alban asylum and Professor Tosquelles. He saw how colonial psychiatry naturalized mental disorders that were determined by social and cultural factors. Scientific reductionism flourished in the colonies, in particular under the authority of Antoine Porot and his influential “Algiers school.” Fanon presented an incisive critique of colonial ethno-psychiatry by exposing its crude racism and justification of colonial oppression. He argued that colonialist psychiatry as a whole had to be desalienated.

As Jean Khalfa and Robert J.C. Young have advanced, Fanon’s political activity was anchored in an astonishingly lucid epistemology and in innovative scientific work and clinical practice. His scientific articles formed a critique of the biologism of colonial ethno-psychiatry and enabled him to reassess culture in its relation both to the body and to history. This is clear in his famous talk on national culture, which he delivered at the Second Congress of Black Artists and Writers in Rome in 1959.

During this period, Fanon experimented with approaches that would make him one of the pioneers of modern ethno-psychiatry. He ultimately distanced himself from institutional therapy after reaching the firm conviction that therapy should, above all, restore freedom to patients and should be carried out within the patient’s normal cultural and social environment. He argued that established psychiatry and mental health institutions “amputated, punished … rejected, excluded, and isolated” patients.

Fanon’s project was to make accessible to patients the creative, cultural, and manual activities that might enable them to become human beings again, with personal aspirations. He wanted his patients to take control of their own lives and to express themselves. With this goal in mind, at Blida-Joinville hospital Fanon established basketwork and pottery workshops, celebrated religious feasts (both Muslim and Christian), organized a film club, sports events and excursions, and, perhaps most important of all, founded a small weekly publication called Notre Journal, launched in December 1953, which recorded the evolution and progress in treating the hospital’s patients.

During his final years, which were spent in Tunis, on top of his political activities he devoted considerable energy to setting up and running a psychiatric day center, which he headed from 1957 to 1959 and which was one of the first open psychiatric clinics in the Francophone world. Day hospitalization is today so common a component of psychiatric care in industrialized countries that it is difficult to sufficiently appreciate the significance of adopting this approach in Tunis during the 1950s.

Fanon, violence and the Manichean psychology of oppression

Colonialism only loosens its hold when the knife is at its throat.

— Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

We can’t talk about Fanon without grappling with his analysis of violence and the psychology of oppression, especially during the present era of destruction and death. What would Fanon say about the colonial genocide and “avalanche of murders” currently taking place in Gaza and other places? What would he say about the traumatic and tormenting effects on Palestinian children, women, and men? How would he analyze the ongoing violence and counter-violence?

In his work, Fanon describes thoroughly the mechanisms of violence put in place by colonialism to subjugate oppressed people. He writes: “Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state.” According to him, the colonial world is a Manichean world, which proceeds toward its logical conclusion: it “dehumanizes the native, or to speak plainly it turns him into an animal.” For Fanon, colonization is a systematic negation of the other and a frantic refusal to attribute any aspect of humanity to that other. In contrast to other forms of domination, colonial violence is total, diffuse, permanent, and global. Treating both torturers and victims, Fanon couldn’t escape this total violence, whose structural, institutional, and personal dimensions he boldly analyzed. In 1956 this led him to resign from his position as Chef de Service at Blida-Joinville Hospital and to join the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN).

Life and work in colonial Algeria, as well as the ruthless way the Algerian War was conducted, with its violence and counter-violence and immense human loss, led Fanon to reformulate his ideas about oppression and mental health and to make the question of violence the focus of his interest and of the first chapter of his final classic work, The Wretched of the Earth. In this book, he describes the Manichean psychology that underlies human oppression and violence.

As Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan has argued, Fanon’s observations in Algeria and elsewhere underscore the fact that colonialism, like the men who run that violent machine, is impervious to appeals to reason and stubbornly refuses to acknowledge the humanity of the other, thereby engendering untold violence. Fanon not only demonstrates the ugly manifestations of violence, but he also explains its liberating role in situations in which all other means have failed. The colonizer depends on and understands only violence, and he has to be met with greater violence: “Violence alone, violence committed by the people, violence organized and educated by its leaders, makes it possible for the masses to understand social truths and gives the key to them.” During Algeria’s struggle for independence, it became clear to Fanon and the Algerian people that when all peaceful measures failed there remained only one recourse: to fight. Palestinians today are doing just that, with formidable courage and heroism but at an incredibly high cost.

Fanon has been unfairly and wrongly accused of being the prophet of violence. In fact, what he does is describe and analyze the violence of the colonial system. Far from making an apology for violence, he judges it unavoidable as a response to the violence of colonization, of domination, of man’s exploitation of man.

Fanon’s letter of resignation from Blida-Joinville Hospital is a moving and principled document of a kind that is rare in psychological literature. It shows the integrity and courage of the man and summarizes the revolutionary and humanistic thrust of his psychiatry. In it he writes: “The Arab, alienated permanently in his country, lives in a state of absolute depersonalization.” He adds that the Algerian War was “a logical consequence of an abortive attempt to decerebralise a people.”

Throughout his professional work and militant writings, Fanon challenged the dominant culturalist and racist approaches to, and discourses on, the natives, such as what he called the “North African syndrome,” according to which “The North African is a simulator, a liar, a malingerer, a sluggard, a thief…” And he advanced a materialist explanation, situating symptoms, behaviors, self-hatred and inferiority complexes within the life of oppression and the reality of unequal colonial relations. He explained that the solution to these issues was to radically change social structures.

Fanon and the psychology of liberation

I, the man of color, want only this: That the tool never possesses the man. That the enslavement of man by man cease forever.

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

Fanon understood that psychiatry must be political. His efforts to place madness in its socio-historical and cultural perspective and to restore integrity to the native’s body and mind were consistent with the larger project of instituting political and social justice. He therefore championed a psychiatry of liberation.

The Algerian war of liberation was clearly a turning point for Fanon’s work as a psychiatrist. The physical loss and psychic dislocation caused by the war cemented Fanon’s conviction that establishment psychiatry and mental institutions in oppressive societies are places of violence, not of healing, and led him to merge his radical psychiatry with the strongest and most practical critique of domination possible, namely the popular struggle for liberation.

Fanon’s active commitment to social liberation also entailed a commitment to psychological liberation. It was indeed his ability to connect psychiatry to politics and private troubles to social problems, and to act accordingly that made him a pioneer of radical psychiatry. What he saw in the FLN health centers, with all of the accumulated anguish of dislocated Algerian refugees, convinced him that the centrality of liberation and freedom to psychiatric patients and to the colonized are two sides of the same coin. This was Fanon’s psychiatry until his death: a noble project of restoring liberty to captives of colonialism and of the psychiatric establishment, and a full commitment to living beings and to any action/clinical practice, writing, and revolutionary violence that could rehabilitate the integrity of people and of basic human values.

Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan has summarized Fanon’s approach to psychiatry eloquently:

a psychology tailored to the needs of the oppressed would give primacy to the attainment of ‘collective liberty’” and, since such liberty is attained only by collectives, would emphasize how best to further the consciousness and organized action of the collective.

Therefore, human interdependence and cooperation, rather than individualism and commodification must be at the heart of the psychology of liberation, which should be about empowering people to change institutions and radically transform social structures, rather than adjusting and submitting to the status quo while making a profit.

According to Fanon, in situations of oppression, we must treat root causes and not only symptoms; we must prevent diseases, not only treat them; we must empower victims to solve their problems, rather than keeping them dependent and powerless; and we must foster collective action, not a self-defeating individualization of difficulties. Herein lies one of Fanon’s most important contributions. A psychology of liberation of the kind advanced by Fanon gives primacy to the empowerment of the oppressed through organized and socialized activity, to restore individual and collective histories that have been derailed and stunted by oppression and colonialism. Whether by peaceful or violent means, it is only through organized struggle that the oppressed can change themselves and overcome the predicaments they face.

Hamza Hamouchene is a London-based Algerian researcher and activist. He is currently the North Africa program coordinator at the Transnational Institute (TNI).