Black people must differentiate between pride in self and their ancestors and any attempt to forge connections with the nation that continues to oppress.

This article was originally published on Boukman Academy.

There’s always been something about Black people wrapped in the American flag that has made me uneasy. For me, it’s a symbolism indicative of the intimate bonds we have with our oppressor, and the way it results in a longing to be accepted by those whose survival is predicated on our destruction. So, when I heard of the 1619 Project, I had immediate reservations. I’m well aware that 1619 was the year that the first recorded enslaved Africans came to the shores of the British colony, which would later become the state of Virginia. I support the need for African descendants in the United States to embrace the difficult challenge of learning about the true history of our constant resistance to and survival of chattel slavery. I believe that this history can unlock keys that will allow us to address our communities most important struggles. Before reading the initial collection of essays, I thought the project would contribute to that work; draw connections from those first enslaved Africans to the present day descendants, still living as captives here in the United States.

I found the opposite to be true.

The 1619 Project contained essays that read to me like pleas of neglected, abandoned, and abused children longing for the affection of their abusive founding fathers while completely ignoring that he ripped them from the care of their Mother; Africa. These essays had the tone of bastard children who refused to believe that their father didn’t love them, and as a result, set out to show him how much of his children they were. So while each essay contained clear indictment of the horrors that Africans and their descendants suffered in the name of the nation that would become the United States and its settler colonial project, those indictments were forgiven and the atrocities presented as necessary for the beautiful contributions we have made; and insistance that our struggle for survival under this oppression qualified us fit to be truly American.

As someone who identifies herself as a descendent of African captives, living behind enemy lines in the United States of America, I was disgusted that Black patriotism to the United States was being used as currency to buy inclusion as Americans; not freedom from oppression, but inclusion as equal to whites. Though I am disgusted, I understand why some Black people seek the acceptance of whites. They want to enjoy the benefits of being part of the dominant group; the power to subjugate others combined with the freedom from accountability. What they seem to overlook is that white domination needs Black inferiority to survive, and the system will crumble if we ever have equality. Many who identify as Black Americans read the 1619 Project essays and swelled with pride, affirming the Project’s aim of highlighting contributions of Black Americans to United States as evidence that they should be regarded as model citizens, to be respected and celebrated as the architects of this country. White Americans however, vehemently rejected the idea that Black people were as American as them.

While I think it is important for us to recognize how deeply imprinted our influence is on everything “American”, I reject the idea that we should credit the United States for our contributions; this type of patriotism jeopardizes our own survival by insisting we fight for white acceptance instead of Black liberation. What saddens me most it the willingness to detach ourselves from our African roots if it means becoming truly American.

Since the initial collection of essays was produced, the 1619 Project has become a Brand, with the most recent release being a 4-episode docuseries streaming through HULU.

Set against a Post COVID-19 backdrop where both intracommunal and police violence are still public health crises for Black communities, gentrification is destroying historic Black neighborhoods in every region of the country, the educational systems are miseducating our children at best and preparing them for prison and military industrial complexes at worst, and despite social medias focus on Black entrepreneurship, the racial wealth gap is widening exponentially. Disregarding that the majority of “wealth” in the United States is debt based, Black people have recently embraced a notion that wealth equals freedom, and have revitalized the conversations about reparations from the United States government for the atrocities committed against us during our enslavement as a way to address these disparities.

Reparations advocacy groups like ADOS (American Descendants of Slavery) and FBA (Foundational Black Americans) are attempting to validate reparations claims by identifying as Black Americans using the reparations model based on tribes indigenous to this country, who are identified as Native Americans. Enter the 1619 Project, a visually beautiful piece of propaganda providing evidence for Black Americans to be viewed as a distinct and important racial group. ADOS make fundamental distinctions among those who would qualify for reparations that exclude those with Caribbean and continental African ancestry who reside in the United States, and FBA attempt to erase Diaspora influences of what we consider Black American culture. Within the context of attempts to receive reparations, I understand the strategy behind the Terminology, but I believe it is divisive and destructive to try to make distinctions between African descendants, whose ancestors were captives in the United States from those whose ancestors were captives and other places in the New World. Especially in an attempt to secure financial compensation from a nation whose biggest export is Black culture, because there is no “Black American” culture without the diaspora and the continent.

Black American culture is African culture that has been adapted to ensure our survival in the United States.

-

You can’t have the Negro spirituals without African spirituality, African rhythms, and melodies.

-

You can’t have the Harlem renaissance without Claude McKay and Marcus Garvey, both of Jamaican ancestry.

-

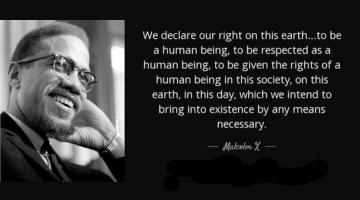

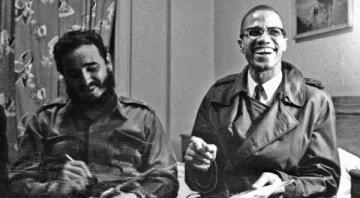

You don’t get Black power without Malcolm X, who has Grenadian heritage and Kwame Ture, who has Trinidadian ancestry.

-

You don’t get hip-hop without the Caribbean because most of hip-hop’s Pioneers like Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash have Caribbean roots.

Again, Black American culture is African culture that we transported through the middle passage to ensure our survival.

Again, it bothers me that Black people in the United States would rather align themselves with one of the most violent, imperialist western nations, than strengthen the ties with the African diaspora, just for a shot at a cash payout and to have a metaphorical seat at the table of brotherhood with their oppressors.

But it is exactly that intent of 1619 project documentary series.

By starting with 1619, it attaches our roots in British America’s 13 colonies. However, if we expand beyond the east coast, there is documentation that not only were Africans enslaved in what is now Mexico, Central and South America and the Caribbean, but many had already self emancipated and had established maroon communities throughout the “New World”. In fact, Before ancestors docked in Virginia, Gaspar Yanga escaped a Mexican plantation in 1570 and began establishing a community that by 1618 had a treaty that established the them as sovereign near what is now known as Veracruz. On the Caribbean coast of Colombia an hour outside of Cartagena, Palenque de Benkos became the first free, maroon community in 1607. One common aspect of all maroon communities in the Americas is that African cultural elements were essential to their self emancipation: spirituality, military strategy and tactics, agricultural abilities, navigation, and all other capabilities were carried with them from various nations on the west coast of Africa. To this point, I argue that marronage is Proto Pan-Africanism and I assert this position as a refutation of anti-African Black American identities that pledge allegiance to the United States like the narratives of the 1619 Project.

The attempt of the 1619 Project to disconnect everything beautiful about the Black experience in the United States from its African roots in an attempt to make a case for us being fully American is disrespectful to our ancestors.

Again, I understand the desire to express pride in the contribution of our ancestors in establishing the most valuable things in this country, especially when we are taught to be ashamed of who we are. But attempting to appeal to your oppressors, that you are good for them, is futile because it’s something they already know. In fact, your value is the basis of their wealth and position in the hierarchy. As I said before, Black culture is the most profitable export in the United States, so whiteness will gladly welcome your efforts to credit them for everything you created. So while “conservative whites” publicly denounce the 1619 Project, it is widely embraced and supported by major media corporations to create products, including a book entitled A New Origin Story, conferences, merchandise, curriculum and teaching material, and a children’s book entitled Born on the Water. The book titles center around the premise that Black Americans are “born on the water” instead of being captives from Africa, and that our “origin story” begins when we arrive in chains, in Virginia, in 1619.

Sure, the contributions of enslaved Africans and their descendants should be included in a true telling of American History, but that is for Europeans in the United States to wrestle with as they work to reclaim the humanity they lost when they created a society based on the construction of whiteness that attempted to dehumanize all indigenous people either aboriginal to or brought to this country. Propaganda like the 1619 Project may in fact be a legitimate starting point for whites, but 1619 should not be considered as a starting point for Africans and their descendants in the United States.

To counter this Anti-African “Black American Identity” we must unite as Pan-Africans across the diaspora and on the continent. We must commit to uncovering the aspects of our Afrikanness that have been our immune system against 400+ years of oppression in the United States and use it as a foundation to reconnect with our distant relatives by going beyond superficial celebrations of Black Cultural traditions like Carnival, and instead understanding the meanings behind the symbolism of masking, dance, parades and other traditions that have been tools of preservation and resistance. We must decenter the United States and anglophone narratives of Blackness in the Americas and resist the egocentric claim that the we are the center of the African Diaspora simply because we are located in the most powerful western imperialist nation. We must also decenter narratives of our enslavement that center attempts at inclusion over those of resistance and liberation; study everything from petite to grand marronage; go beyond major rebellions and shed light on the mundane everyday resistance our ancestor engaged in; like loving each other, educating our youth, and honoring our ancestors. Study the Reconstruction period when emancipated Africans attempted to establish homelands on American soil with names like Afrikville and Africa Town, a time when many were committed to finding their ways back to Africa. We owe it to ourselves, our ancestors and future generations not to allow our history as Africans in the United States to be whitewashed by efforts like the 1619 Project that essentially allow witness ownership, and thus profitability, of African contributions to America. If anything, we should be committed to divesting our genius from this nation, and redistributing it throughout the diaspora.

Dr. Charity Clay is a professor in Critical Race Sociology at Xavier University of Louisiana. She has an upcoming book focused on police terrorism against Black communities, as well as a podcast on how white supremacy benefits from Black protest. She can be found on her website www.urfavcharity.com and on Instagram @urfavcharity.