Reaching Beyond “Black Faces in High Places”: An Interview With Joy James / Photo: Dr. Joy James

White supremacist culture is a permanent site of predatory consumption, extraction and violation.

“Black masses are consistently told by the Black elite pundits, academics, nonprofit leaders or movement specialists to stay in line and follow.”

With the advent of the Biden administration, it’s a crucial time to examine the role anti-Blackness plays not only when it comes to overt white supremacist actions, but also the actions of the government — and other forces of power — more broadly.

What does Black suffering look like historically? What is the complex relationship between “progressive” racial politics and the subtle operations of capitalism? How is Black suffering monetized, especially within the context of celebrity activism? How do we ensure that our efforts to resist anti-Black racism are congruent with fighting on behalf of Indigenous peoples?

To come to terms with these pressing questions, I spoke with Joy James, who is Ebenezer Fitch Professor of Humanities and professor in political science at Williams College. She is the author of Resisting State Violence; Transcending the Talented Tenth; Shadowboxing: Representations of Black Feminist Politics; and Seeking the Beloved Community: A Feminist Race Reader. James has edited volumes on politics and incarceration, including Imprisoned Intellectuals and The New Abolitionists.

George Yancy: Black suffering is pervasive; its arc long. As a scholar-activist who takes seriously such themes as radical politics and abolitionism, when will Black suffering “bend”? Or is it the case that Blackness is always already a site of “permanent” suffering or oppression? To put this metaphorically, are we still in the holds of slave ships? When I ask this question, COVID-19, and Black vulnerability to it, feels almost normative vis-à-vis the death of Black people.

Joy James: It is always good to be in dialogue with you, George. Your first question relates to an existential theme that we discussed years ago about “misery” following the publicly displayed police executions of Eric Garner in Staten Island and Michael Brown in Ferguson.

I do not think that Blackness as a permanent site of suffering/oppression is the defining marker of who we are. I would say that white supremacy and its violent iterations are clearly historically documented. Think here of enslavement, the convict prison lease system, black codes, Jim Crow, voter disenfranchisement, redlining, and the spectacular war and violence as reflected in Tulsa, Oklahoma’s, Black Wall Street 1921 bombing, and burning and mass murders of Black residents, in which white police looted and lynched, re-enacted decades later by Philadelphia police in the 1985 bombing of the MOVE house and city employees deciding to burn down an entire Black neighborhood. White supremacist culture is a permanent site of predatory consumption, extraction and violation. Its aggressions seek to distract from the dystopia depicted in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (also marked by Eliot’s reported affinity to antisemitism).

Oppression and devastation preceded and engineered the creation of the “Black”; we are just in a long dirge in which resistance and rebellion follows repression and adds shouts, prayers, and expletives. How do we resist? We do so in innumerable ways through arts and activism, betrayal and code switching as “shape shifting” (as noted by a brilliant webinar, “Octavia Butler: Slow Read-A-Long” led by young Black feminist intellectuals/artists).

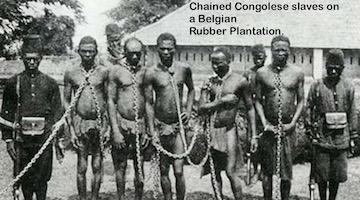

We are in the “hold”: slave ships, dungeons, prisons, jails, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) family centers (in Texas, Haitian families form 40 percent of the population) and “womb collector” hysterectomies that seem to “favor” Black women/mothers. Yet the rebellion of whistle blowing was done by a sister, Dawn Wooten, who reported both medical violations and medical neglect concerning COVID-19. From the hold of a slave ship to solitary confinement in prison or psych wards, our people fight for life in the presence of death by caring for ourselves and others.

When I think about the theme of Black leadership and hope, I think that there were many who may have conceptualized Barack Obama’s presidency as the panacea for anti-Black racism, that he might help the arc of the moral universe to bend. I think that such an expectation was unreasonable for many reasons, one being that he was commander-in-chief, head of the American empire. My question has to do with radical political change and its possible realization from within the space of state power. I’m thinking here of Kamala Harris but trying to do so beyond her symbolic significance as the first Black and South Asian American woman to hold such political power. What can she do that might be identified as politically radical? After all, as you have argued elsewhere, hegemonic structures exist alongside a diversity of Black faces. As with Obama, her allegiance is to the American empire first. What would it take for “insiders” to bring about radical change, counter-hegemonic change or is the instigation for genuine radical change only possible as “outsiders”?

We both work for private corporations defined as nonprofit educational institutions. We have no romantic illusions about the nature of our jobs. We were hired to affirm and stabilize the elite university/college. We can demand accountability for white supremacist/(hetero)sexist eruptions and ask for security (which can be denied or curtailed), but we do not pretend that these institutions exist to bring justice to the world or function in the interests of the oppressed (particularly if such institutions are gentrifying neighborhoods and taking donor money from right-wing oil/gas mogul Charles Koch). If you don’t have illusions about your day job and its functions to stabilize (while admonishing excessive violence from) racial capitalism, why would you have illusions about the government/state investment in racial capital?

No one forced Barack Obama to be the first Black imperial president for a nation whose democracy was built on racial conquest and rape. He wanted the gig. Black people, working class or laboring poor or dispossessed of paid labor, did not draw up petitions to draft Obama to primary Hillary Clinton (whose policies were more neoliberal progressive than Obama’s in the 2007/2008 primary). White wealthy donors seemed to be his early backers along with a slice of the Black elite that had not yet peeled off from the Clintons. Anti-Black racism was furthered by Clinton policies and never seriously challenged by Obama policies.

If the big ask now is to “see Black faces in high places,” then enjoy the Biden-Harris administration. It is definitely better to not be taxed to pay for violent white nationalists and the salaries and pardons of white-collar and war criminals. However, no longer being taxed to pay for predatory rogues, rot, and incompetence is not the definition of transformative justice. Empires thrive on violence and racial capitalism.

“Anti-Black racism was furthered by Clinton policies and never seriously challenged by Obama policies.”

Harris campaigned on “Joe.” Not just for the president-elect’s policies (which are not based in transformative justice) but for his persona as the caring white leader who can bargain with those who empowered white nationalism and the devastation of the health and well-being of the laboring poor and working class. Biden’s revolving door of the Obama administration attempts to re-center D.C. into a romanticized past. There should be more money for jobs and social welfare programs — as much money as corporations and bureaucrats deem “prudent” from those exploited and abandoned by the corporate state and its racial/sexual/religious anima. With the (neo)liberals back, expect less autonomy for independent thinking as everybody will be charged to “get on board” with the elite-driven programs that never adequately addressed white supremacy, poverty, and violence against women, children, LGBTQ and are not designed by those most negatively impacted by racial/colonial capitalism.

Black masses are consistently told by the Black elite pundits, academics, nonprofit leaders or movement specialists to stay in line and follow. But follow whom? What is the possibility that Obama and Harris have been sold to Black people by corporate/state elites as responsive to the needs of the Black mass and the impoverished and denigrated? Biden’s only strong competitor was Bernie Sanders who campaigned on Medicare for All — until Black civil rights icons merged in the political machine with the Obama/Clinton DNC to warn folks not to go “too left” and to stop asking for “free stuff.” How much misery from 20 million COVID-19 cases and over 400,000 deaths in the U.S. could have been mitigated or prevented if universal health care existed? Where Black politicians and advocacy Democrats share the same donor base and think tanks, and propaganda networks with the Democratic National Committee (DNC), it is illogical to expect transformative justice. There are possibilities with the incoming representatives such as Cori Bush and Jamaal Bowman, and the sort of rogue Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), if their roles as productive disruptors and creators for the (Black) masses are not cannibalized by the party machine.

Given the previous question, how do we engage in “free discourse,” that is, a discourse that challenges how liberals have defined freedom and liberty? What does a political vision of freedom look like outside of logics that maintain the status quo, that imprison not just our discourse but our political imaginative capacities?

Free discourse is the ability to be radical in service to the disenfranchised and imprisoned without being attacked. Obama instituted the most repressive laws against whistleblowers/investigative journalists. To stop the white (Black?)-washing of the Obama legacy and acquiescence to heirs apparent, radicals would have to negotiate the terms of struggle, and sacrifice and insults for attempting to illuminate contradictions, hegemonic betrayals, and ideology masking performative politics within celebrity activism/education and accumulation from the monetization of Black suffering. There is razor-like irony at play in performative politics inching towards the Achilles’ heels of radicals. Black radicals are lectured to stop being so “lefty” by Joe and Barack (and others who castigate as “purity politics” analyses which decades ago would have been described as principled rather than opportunistic). Despite the millions protesting against the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, police and white supremacist killings and dishonoring of our people (Anjanette Young in Chicago) or deaths due to medical neglect such as MD Susan Moore for whose death no one will be accountable; her last testimony to us warned: “Being Black up in here, this is what happens.”

Historically, anti-Black violence was used to enslave and accumulate wealth for non-Blacks, including Indigenous tribes granted “civilized nations” status if they trafficked/enslaved Black people. Some doubt New Mexico Congresswoman Debra Haaland, named the first Indigenous secretary of the interior by Biden, will positively respond to the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen/Black Indian petition to seek tribal recognition and monetary/land support. Anti-Black violence was also embedded in Biden’s choice for new Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack; the former Ag guy in the Obama administration who expedited Black farmers’ loss of their lands and livelihoods due to denial of civil rights protections. Violence from 18th century slave ships to 21st century Obama administrators enabled accumulation through Black loss. One can monetize Black suffering and raise revenue through private prisons, repressive charter schools, Wells Fargo fraud targeting Black homeowners. Those opposed to anti-Black violence and dispossession can also monetize Black suffering by refashioning the narratives, stories, and trauma into marketable writing and lecturing, visuals in fashion wear, public relations, voter registration/mobilization, nonprofit sector jobs, punditry on news shows/podcasts. Black misery is profitable for racists and anti-racists.

Making money is a precondition of surviving under capitalism (rent, food, competent health care, clothing, education, etc.). Yet Black street activists or imprisoned activists — whose heads are cracked open by violent cops/guards and white supremacists — take the greatest risks for transformative justice and reap the smallest percentage of monetary gains from advocacy democracy. Explaining Black people or anti-Black terror to non-Blacks, reassuring Blacks that there is a way to evolve out of predatory anti-Blackness without revolutionary struggle is lucrative. Those funds garnered from the narratives whose radical love leads to radical risk rarely go back into Black institutions, community centers, houses of worship, food banks, freedom schools and most importantly, transformative political education, what Fred Hampton defined as the only real weapon against oppression.

The Black Lives Matter movement is crucial as a dynamic process of bringing attention to various forms of anti-Blackness. Meanwhile, Indigenous struggles are often erased even in the middle of racial justice movements. Speak to the theme of solidarity here. I’m thinking of Martin Luther King, Jr., where he says that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” It seems to me that marginalized people can’t claim liberation until Native Americans are also liberated. In fact, Native American suffering, or so I would argue, is often elided.

There were debates before an abolitionist platform changed its motto statement from a quote by a Black academic to a declaration for sovereign rights by an Indigenous Dakota leader seeking to secure the roads into the reservation despite a Trump-leaning governor. The attempts of a collective of radical Black women abolitionists to highlight Article 16 of the Ft. Laramie Treaty as “abolitionism” was permitted as a momentary intervention. Radical Black women and allies could only temporarily refocus the abolitionist motto. We later circulated a statement asserting that Indigenous nations/elders — not Black, white, or people of color (POC) academics—determine the status of those who claim to belong to Indigenous communities (and build careers as representatives of said communities). Still later, we brought attention to the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen’s petition challenging anti-Black racism to New Mexico Congresswoman Deb Haaland, the first Indigenous nominee for secretary of the interior.

In the U.S., we grapple with white supremacy, “POC” ethnic chauvinism toward Indigenous people, and anti-Black racism among Indigenous people. We lack consensus on how progressive multiracial “coalitions” should respect the desires of Black working/laboring class people and Indigenous reservation communities to define their needs and assert autonomy. Revolutionary acts respect global Indigenous autonomy and culture, including Indigenous peoples in Africa, Australia, the Americas and beyond.

Derrick Bell analyzed “interest convergence” in which the strongest party steers the coalition and so betrays the needs of the less empowered by the racial state and capital. Alliances with hegemonic wealthy white liberals tilt the balance of the scales. If Indigenous elites are white wealth-identified, they will not align with Black people unless they are also white wealth-identified. Either way, Black masses are marginalized.

“We lack consensus on how progressive multiracial “coalitions” should respect the desires of Black working/laboring class people and Indigenous reservation communities to define their needs and assert autonomy.”

I am curious about why Afropessimism is so vilified for its contributions not just its limitations. Its contributions are to cut through the smoke and mirrors of banal coalitions that castigate Black people for being “too Black,” that is, for addressing the need to be free from anti-Blackness/white supremacy through a political project that forecloses compromise (the “virtue” of coalitions that are not dominated by radical Black masses). Perhaps we could focus on what we have in common as Indigenous, Black Indigenous and Blacks: rebellion, hence the need to free our political prisoners such as: Leonard Peltier, Mutulu Shakur, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Joy Powell, Russell Maroon Shoatz, Sundiata Acoli, Veronza Bowers, Ruchell Cinque Magee and others who rebelled against conquest and genocide.

Let’s see if we can form an alliance around the recognition of the rights of Black Indigenous people alongside the recognition of non-Black Indigenous rights to land and autonomy. Also, let’s see if we can discuss reparations with specificity, not generalizations; that this is imperial democracy built on stolen Indigenous land and with stolen Black labor. Let’s see if we can collectively mourn the mass rapes of Black women baked in the three-fifths clause of the U.S. Constitution so that former slavery-bond states (southern “red states”) deployed terror for reproduction to accumulate political power and pro-plantation presidencies. Let’s see if we can fight the murders and disappearances of Black women/girls/trans interlocking with the battles to stop the murders and disappearance of Indigenous women/girls/two-spirit people. We need each other as allies in struggle, but as Black people our struggles remain distinct; it is not a hierarchy in oppression, it is a specificity in combating it that we as radicals demand.

Joy, you have written about spirituality and Black feminist thought. As an approach to healing so much human suffering, speak to the importance of a specifically spiritual awakening that is necessary for this country. Also, in what ways does your understanding of spirituality overlap with Black feminist thought in terms of rethinking relationality, community, and humanity?

Spirituality and trauma forced me to recognize the limited capacity of bourgeois Black feminist thought and reflect on how the ideological markers of Black feminism were blended into hegemonic discourse and “progressive” marketing.

2021 is the 50th anniversary of the Attica rebellion. Think about how those in Attica maintained the structures of their captivity under pain of torture or death, until they chose to risk life to defeat a living death. Trustees and imprisoned nurtured and nursed each other and performed the labor under penal slavery (the 13th amendment to the U.S. constitution codifies enslavement to incarceration) that allowed the massive prison to exist. Rejecting the first or early stage of contradiction and caretaking and collaboration, the captives decided to organize a prison strike for human rights and dignity. They allowed spirit to lead them into mass movement and rebellion (some were inspired by the assassination of George Jackson).

After taking over the massive prison, they had to rebuild community as a maroon camp within a prison, setting up a food delivery system, waste removal, political education, a medic site, security, spokespersons to address the press and public about their Liberation Manifesto. Spirit formed community out of chaos, amid precarity and extreme vulnerability they were able to forge unity and purpose for transformative justice.

From that third stage, captives were moved to the fourth and final stage, that of war resister when the racial state born with a lust for slavery treated the rebellion for human and civil rights as an act of war and responded with Vietnam military surplus (imperial wars amplify domestic supremacist violence); the National Guard called in by president and governor killed Black and Brown resisters, maroons, community builders and defenders; later guards would torture and murder rebels once the prison was retaken.

Four spirit-filled stages — conflicted caretaker, movement activist, maroon, war resister — in which one risks life to achieve life outside of the fetid hold of the slave ship, and in the process, one’s “losses” transform into victory in which the birth of rebellion becomes a story of origins and birth making. To rebel, to have any moment of freedom meant that the world was in the moment born anew, the air — fresher, songs — sweeter, fear and dread, exhilarating with hope mixed with despair.

George Yancy is the Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Philosophy at Emory University and a Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College. He is also the University of Pennsylvania’s inaugural fellow in the Provost’s Distinguished Faculty Fellowship Program (2019-2020 academic year). He is the author, editor and coeditor of over 20 books, including Black Bodies, White Gazes; Look, A White; Backlash: What Happens When We Talk Honestly about Racism in America; and Across Black Spaces: Essays and Interviews from an American Philosopher published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2020.

This article previously appeared on Truthout.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com