Ousted former Peruvian President Pedro Castillo, arrives for his trial on Tuesday, March 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Guadalupe Pardo)

The trial of former Peruvian president Pedro Castillo, the victim of a 2022 lawfare-style coup, has begun. The legal process used against him is a sham covering up the human rights abuses committed against Castillo and the people of Peru.

On March 4, José Pedro Castillo Terrones, Peru’s first Indigenous rural president, went before the Supreme Court in what he, his lawyers and supporters have called a “show trial” for the supposed crime of rebellion. Since being overthrown in a 2022 coup, Castillo has spent the past two years in Penal Barbadillo (a prison) in conditions described as torture. He is said to be under pre-trial detention, itself a violation of his human rights.

Shortly after Castillo gave an announcement that he would pursue closing Congress, a primary demand of the Peruvian masses for years, Congress swiftly moved to impeach him. In a chain of procedural missteps, Congress rammed through (illegally, as his lawyers argue) the impeachment of Castillo. One day prior to this, US Ambassador to Perú Lisa Kenna met with Peruvian Defense Minister Gustavo Bobbio to turn the military against Castillo, and had met with Castillo’s Vice President Dina Boluarte. The specter of US interventionism, unsurprisingly, was behind this coup. This led to a mass uprising, predominantly but not exclusively of indigenous campesinos coming down from their mountain homes to city centers to protest their popular will being violently denied. What followed were some of the darkest hours of Peruvian history, with state violence against an unarmed population that led to the death of at least 70 civilians and over a thousand injured.

Since the coup on Dec 7, 2022, the Peruvian masses have remained mobilized in the streets against a rising crime wave (facilitated and encouraged by the state itself), for International Women’s Day, and many more rounds of protests against the coup regime and its neoliberal policies. Through this, Castillo remained locked up in Barbadillo, the same prison that housed Alberto Fujimori, until his release and later death.

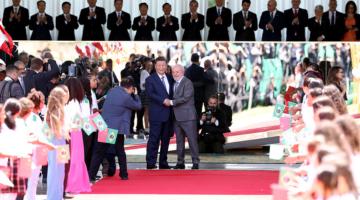

Castillo’s case demonstrates a clear tactic of US/Western imperialism. Lawfare has not only been used against the Peruvian people in this instance of judicial and congressional persecution. Instead, we see a worrying trend throughout the region where it is used to maintain the dictates of the Monroe Doctrine - “America for the (North) Americans.” From Lula in Brazil to Evo Morales in Bolivia, the courts have been used as a new battleground to pursue the same goal - overthrow any government that poses a threat to US/Western interests.

As of March 10, Castillo has announced he is on hunger strike, in protest of the “injustice committed against (him) for the charge of ‘rebellion.’”

The following is a translation of an article published in the Argentinian newspaper Pagina 12, by his international lawyers, Eugenio R. Zaffaroni and Guido L. Croxatto.

Pedro Castillo Faces a Farce of a Trial

From the very first moment we took on the international representation of Pedro Castillo, we recommended the legal strategy that he seems to have finally opted for on March 4: a rupture trial.

Since both of us were prohibited from entering the Barbadillo[1] prison to visit our client, it became clear to us that the judicial process (like the vacancy[2]) was irregular. There was no adherence to the Constitution. It did not represent legality. Castillo was not allowed free access to his lawyers.

Just a few hours after the improperly vacated president formally appointed us, the INPE issued a statement prohibiting the entry of "foreign lawyers" into the country's prisons from that point on. An arbitrary measure contrary to the American Convention, taken solely to harm Castillo. To deny him his basic rights: his right to defense.

Castillo does not recognize the validity of the court judging him. Jacques Vergès distinguished some time ago between two types of trials: rupture and connivance. In the first, the authority of the judges is not accepted. Why have lawyers if the sentence is written in advance?

From a criminal perspective, Castillo's speech did not even meet the minimum requirements of a message to the nation. In terms of typicity, it does not constitute the crime of rebellion. If it were an attempt, it was not suitable for the proposed purpose, which is why it can never be a crime. But the criminal aspect is irregularly substituting a more primary aspect: the constitutional one, which is even more important, especially when dealing with a president whose immunity was never properly revoked.

Constitutional scholars from the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (whom no one would accuse of being Castillistas[3]) agree in a dossier that Congress violated both its own regulations and the Peruvian Constitution by unconstitutionally impeaching Castillo. The Ombudsman's Office issued a statement clearly outlining the steps to follow for the vacancy to be constitutional. They did not follow them. They invented another process, which was not appropriate (because they did not have enough votes to do it legally). And this second process, in turn, was misapplied. Castillo was irregularly "vacated," with 3 fewer votes than the law requires. This shows that his vacancy is procedurally null. It was carried out in violation of the law. Violating the procedure. This is not a secondary matter. Constitutional due process matters.

After this outrage, the irregular imprisonment of an improperly vacated president follows. That is why the trial ends up being a farce: because the first thing that should have been done is to carry out a vacancy in accordance with the law. Castillo demands a fair political trial, in accordance with the law, something he has not had so far. The place for this trial is not a criminal courtroom in the Supreme Court: it is Congress. If Castillo were to accept the legitimacy of the criminal process, he would be validating a null act: the vacancy.

The corruption charges are not appropriate when the president was improperly impeached. But they have not gone anywhere either. They were excuses to keep the president deprived of his liberty. After this arbitrary detention, they have not found any evidence against him. Nothing. The prosecutor who initially pursued Castillo (inventing news that later proved to be false) was accused herself of leading a criminal organization.

Castillo, as the president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, said, does not even have the means to pay his lawyers. He is innocent of all the charges against him. It is amusing that some congressmen say that Castillo "cannot pay us" the two of us: we are not defending him for money, but out of conviction, because he was vacated in violation of the law. The irregular vacancy of an elected president cannot go unpunished for Peru.

(Former lawyer) Guillermo Olivera denounced that he suffered what in Peru is called "reglaje[4]." That he was followed. He had to go into exile in Madrid. Another lawyer denounced that there was always a car parked in front of his office that followed him when he left. Benji Espinoza, who was Castillo's lawyer, just reported that his office was broken into and everything was stolen: but especially his personal computer. These attacks, intimidations, and surveillance of Castillo's lawyers (and former lawyers) are not coincidental.

Harassing lawyers is not the way. Respecting constitutional procedures to vacate a president is. You cannot call just anything a "vacancy," much less a process that does not meet the minimum terms that the Constitution establishes (and demands!) for the vacancy to be legal. A congressman should know this. The defense is not saying that Castillo cannot be vacated. It is only saying that if they want to do it, they must do it in accordance with the law, something that—so far—has not happened. They cannot do it any way they want, but only in the manner prescribed by the Constitution and the rules of Congress.

In the letter we delivered in Mexico, Castillo asks for "a fair political trial, in accordance with the law." Something he has not had so far. The criminal process cannot replace the constitutional instance, which must happen first. A false vacancy cannot be covered up with another criminal procedure. When we advised Castillo on a rupture process, we had this in mind: that the criminal farce (and the number of hearings in the same week, when the maximum is two, which shows the haste to convict him) is being used to disguise the fact that the prior constitutional process was irregular. The rupture of the criminal process can serve to draw attention to this.

**En Español**

El 4 de marzo, José Pedro Castillo Terrones, el primer presidente rural e indígena de Perú, fue ante la Corte Suprema en lo que él, sus abogados y sus seguidores han calificado como un "juicio espectáculo" por el supuesto delito de rebelión. Desde su derrocamiento en un golpe de Estado en 2022, Castillo ha pasado los últimos dos años en el penal Barbadillo (una prisión) en condiciones descritas como tortura, bajo detención preventiva, lo que en sí mismo es una violación de sus derechos humanos.

Poco después de que Castillo anunciara que buscaría cerrar el Congreso, una demanda principal de las masas peruanas durante años, el Congreso actuó rápidamente para destituirlo. En una serie de errores procesales, el Congreso impulsó (ilegalmente, según argumentan sus abogados) la destitución de Castillo. Un día antes de esto, la embajadora de Estados Unidos en Perú, Lisa Kenna, se reunió con el ministro de Defensa peruano, Gustavo Bobbio, para volver al ejército en contra de Castillo, y también se había reunido con la vicepresidenta de Castillo, Dina Boluarte. El espectro del intervencionismo estadounidense, como era de esperar, estuvo detrás de este golpe. Esto provocó un levantamiento masivo, predominantemente pero no exclusivamente de campesinos indígenas, que bajaron de sus hogares en las montañas a los centros urbanos para protestar contra la violenta negación de su voluntad popular. Lo que siguió fueron algunas de las horas más oscuras de la historia peruana, con violencia estatal contra una población desarmada que resultó en la muerte de al menos 70 civiles y más de mil heridos.

Desde el golpe de Estado del 7 de diciembre de 2022, las masas peruanas han permanecido movilizadas en las calles contra una creciente ola de delincuencia (facilitada y alentada por el propio Estado), por el Día Internacional de la Mujer, y muchas más jornadas de protesta contra el régimen golpista y sus políticas neoliberales. Durante todo esto, Castillo permaneció encerrado en Barbadillo, la misma prisión que albergó a Alberto Fujimori, hasta su liberación y posterior muerte.

El caso de Castillo demuestra una táctica clara del imperialismo estadounidense/occidental. El "lawfare” (guerra jurídica) no solo se ha utilizado contra el pueblo peruano en este caso de persecución judicial y congresional. En cambio, vemos una tendencia preocupante en toda la región donde se utiliza para mantener los dictados de la Doctrina Monroe: "América para los (norte)americanos". Desde Lula en Brasil hasta Evo Morales en Bolivia, los tribunales se han utilizado como un nuevo campo de batalla para perseguir el mismo objetivo: derrocar a cualquier gobierno que represente una amenaza para los intereses de Estados Unidos y Occidente.

Hasta el 10 de marzo, Castillo ha anunciado que está en huelga de hambre en protesta por la "injusticia cometida contra (él) por el cargo de 'rebelión'".

A continuación, se presenta la traducción de un artículo publicado en el periódico argentino Página 12 por sus abogados internacionales, Eugenio R. Zaffaroni y Guido L. Croxatto.

Pedro Castillo se enfrenta a una pantomima de juicio

Se ha iniciado en Perú una pantomima de juicio contra el presidente constitucional Pedro Castillo. La legalidad peruana se rompió cuando Castillo fue preso (sin retiro de inmunidad, sin vacancia legal, sin proceso, sin moción, sin votos) y usurpó su función su vicepresidenta, traicionando el mandato popular y ordenando una represión indiscriminada que costó la vida a decenas de personas, entre ellas mujeres y niños. La represión no fue contra cualquiera: fue contra quienes habían votado a Castillo.

Castillo se presenta ante este escenario sin abogados, es decir, que eligió correctamente el camino de no prestarse a la pantomima. Asume lo que se llama un proceso de ruptura, cuando no vale la pena defenderse ante supuestos jueces que ya tienen decidida la condena. Nada mínimamente jurídico cabe esperar de personajes que no se inmutaron frente al indulto para un criminal de lesa humanidad, entre otras cosas responsable de la esterilización forzosa de cientos de miles de mujeres. Se les nota demasiado que ocultan bajo la toga el hacha del verdugo.

Castillo es el presidente constitucional del Perú, aunque esté preso. Lo es porque fue destituido por la fuerza y no por el derecho. El Congreso no tenía los votos para destituirlo constitucionalmente, y por eso fue vacado –como dicen en Perú- sin los votos necesarios. Esto lo dicen los constitucionalistas de la Pontificia Universidad Católica –que nunca parecieron ser partidarios del presidente- y también la Defensoría, además de probarlo la matemática.

Se inventaron hechos de corrupción contra Castillo, como contra Correa, Lula, Evo, Cristina, etc., pero con la particularidad en este caso de que la fiscal que comenzó a inventarlos fue más tarde destituida por liderar una organización criminal.

El presidente Castillo llega ante sus condenadores siendo presidente según la Constitución y acusado de una tentativa de rebelión, delito que el código penal define como alzarse en armas. Su rebelión consistió en pronunciar un discurso, cuando se sabía que nadie habría de levantar un arma y, por cierto, la única arma que se levantó fue la de su propia custodia para detenerlo, incluso ante los ojos de su hija, una niña. Nunca le retiraron la inmunidad.

Todos sus condenadores saben –porque a diferencia de Castillo cursaron la carrera de Derecho- que cuando se quiere intentar la comisión de un delito con un medio absurdamente ineficaz (matar con rezos, por ejemplo), eso se llama tentativa inidónea y su código dice explícitamente que no debe ser penada, aunque aleguen el absurdo argumento de que en otra circunstancia eso hubiese sido peligroso: no hay acción humana, por inocente que sea, que en circunstancias diferentes no sea peligrosa (la práctica de tiro al blanco, por ejemplo). Las conductas no se juzgan por eso en cualquier otra circunstancia, sino en las precisas circunstancias en que sucedieron.

También saben que constitucionalmente Castillo es el presidente. No lo ignoran, algunos incluso serán profesores en alguna universidad, no sé si sus alumnos les creerán cuando hablan de derecho. Tienen plena consciencia de todo eso: la que parece faltarles es el otro sentido de la conciencia, la que en algún momento hace escuchar su voz a toda persona honesta, aunque sea en el último momento de su existencia.

Castillo no necesita abogados en esta parodia, su presencia no haría más que legitimar una escenificación para darle la apariencia de un juicio. Pero tampoco se puede ignorar que sus abogados y ex abogados fueron sometidos a aprietes llamados reglajes en Perú. Guillermo Olivera tuvo que irse del país; otro abogado denunció la presencia de un automóvil que lo seguía permanentemente; Benji Espinoza acaba de denunciar que robaron en su oficina, llevándose su computadora personal. Parece que el régimen de facto de la señora Boluarte teme que en medio de la teatralización judicial alguien invoque el derecho.

Es obvio que el presidente Castillo no responde a los intereses colonialistas y de momento -para eso- está la señora Boluarte, hasta que deje de serles útil y la dejan librada a las fieras, quizá a los mismos personajes togados que mantienen preso y condenan a un presidente constitucional, mal vacado. La vacancia tiene un procedimiento que no fue respetado.

Pero como si todo lo anterior no fuese suficientemente vergonzoso, lo más indignante es el otro motivo no confeso de la condena al presidente Castillo: racismo puro, un campesino serrano no puede ser presidente, no lo tolera la gente de bien, profundizando la herida que se remonta a la colonia y que reafirmó la república en 1821. Se trata de una herida sangrante que atraviesa toda la historia peruana y que siempre denunciaron sus mejores historiadores, pensadores e intelectuales. El cholo no puede ser presidente: este es el más aberrante e indignante motivo oculto de esta condena y que no debe callarse ni mucho menos dejado de lado. ¿Para qué abogados, cuando es el odio racista lo que lleva a una condena y lo demás son pretextos?

José Arguedas, escritor que aprendió primero la lengua de los "sirvientes" que lo criaron, escribió un poema titulado Llamado a algunos doctores. Su lectura anti colonial (y muy crítica del derecho peruano) podría servir a los jueces que hoy pretenden condenar sin pruebas a un presidente constitucional, que en todo caso debiera ser repuesto y juzgado (en un juicio político, no penal) conforme a derecho. Hasta ahora eso (que es lo básico para vacar a un presidente, y lo primero que pide la constitución) no sucedió. Castillo fue vacado porque nunca cedió a las extorsiones. Si hubiera "negociado" con el Congreso (que tiene una desaprobación mayor al 90 por ciento) seguiría cómodamente sentado en el Palacio. Por suerte para Perú, no lo hizo.

[1] Barbadillo: It is a prison administered by the INPE located within the Directorate of Special Operations (Diroes) of the Police, in the district of Ate, Lima.

[2] Vacancy: It is the situation by which the president of Peru, Pedro Castillo Terrones, would be deprived of continuing to exercise his functions as president. He is removed from office.

[3] Castillistas: Supporters linked to Pedro Castillo.

[4] Reglaje: Reglaje is a crime in Peru that involves monitoring or following people to facilitate the commission of other crimes. It is also known as marking. It is a crime of endangerment that threatens public tranquility.

Clau O'Brien Moscoso is an organizer and co-coordinator of the Black Alliance for Peace Haiti/Americas Team. Originally from Barrios Altos, Lima, she grew up in Kearny, New Jersey. She attended college, lived, and organized in New York City for 15 years, and is now based in Lima, Perú, writing about Latin America and the Caribbean for the Black Agenda Report.