Bayard Rustin points to a map showing the path of the March on Washington, in New York City, on Aug. 24, 1963. AP

The recent Obama-produced retelling of the life and work of Bayard Rustin is better judged by what it leaves out - his legacy of counterrevolutionary action designed to defang radical movements.

On May 9, 1968, Fred Nauman, a 38-year-old science teacher at Junior High School 271 in Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood, was a few minutes into his first class when he was summoned to the principal’s office, where he was handed an envelope. It read:

Dear Sir:

The Governing Board of the Ocean Hill–Brownsville Demonstration School District has voted to end your employment in the schools of this District. This action was taken on the recommendation of the Personnel Committee. This termination of employment is to take effect immediately.

In the event you wish to question this action, the Governing Board will receive you on Friday, May 10, 1968, at 6:00 P.M., at Intermediate School 55, 2021 Bergen Street, Brooklyn, New York.

You will report Friday morning to Personnel, 110 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, for reassignment. Sincerely,

Rev. C. Herbert Oliver, Chairman Ocean Hill–Brownsville Governing Board

Rhody A. McCoy Unit Administrator

Nauman was one of 19 teachers and administrators who had received a notice of reassignment from a group of Black and Puerto Rican parents planning an ambitious takeover of their neighborhood schools. More than a decade after the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. the Board of Education decision, New York City’s schools were more segregated than ever, test scores were abysmal, dropout rates high, and classrooms overcrowded. Worst of all, neither the Board of Education nor the United Federation of Teachers, or UFT, showed much interest in educating children of a darker hue.

Influenced by Malcolm X’s pedagogy of self-reliance, the African American and Puerto Rican parents in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district decided that they would assume control of their children’s education, hiring their teachers, and supervising a curriculum that was intended to imbue the kids with both the critical thinking skills and the confidence that they would need to get ahead in a European settler state that is reflexively antagonistic to nonwhites.

Supported by Mayor John Lindsay and the Ford Foundation, organizers pitched the idea of a pilot project to the city’s Board of Education in July of 1967, and as the promising experiment drew to a close the following spring, neighborhood parents, activists and clergy began to put their plan into action ahead of the school term that would begin in the autumn of 1968.

The first order of business was hiring the right teachers for the job, and that meant the reassignment of teachers like Nauman, who was a chairman for the United Federation of Teachers, representing 55,000 public school teachers, a good many of them Jewish. Signing its first union contract in 1961, the UFT succeeded the more radical Teachers’ Union, which had been destroyed by the communist purges mandated by Congress’ labor-busting Taft-Hartley Act, enacted in 1947. The United Federation of Teachers discarded the “civil rights” model of labor organizing which animated the workers’ struggle in the New Deal era by championing investments in the broader community rather than merely advocating for fatter paychecks or more vacation days for rank-and-file employees.

Their narrow interpretation of labor unions led the United Federation of Teachers to interpret community control as a challenge to their rights won by negotiating a collective bargaining agreement with the city. Union leaders such as Nauman and UFT President Albert Shanker, also Jewish, objected to the governing board’s choices for principals in the Ocean Hill–Brownsville schools, opposed changes in the curriculum to reflect the students’ African heritage, and insisted that the largely Black and Puerto Rican community did not have the right to reassign teachers, no matter how uninspired and underperforming they were. According to Jerald Podair in his marvelous account, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites and the Ocean Hill - Brownsville Crisis, the project’s African American superintendent, Rhody McCoy

“had begged union leaders to be more flexible. They wouldn’t listen. He had told Nauman and his colleagues that this was an experiment in community control, and if this did not mean control over personnel, finances, and curriculum, what did it mean? They didn’t understand. The union seemed to go out of its way to throw bureaucratic impediments at him. He was trying to be reasonable, but the white teachers wouldn’t meet him halfway. It was as if they didn’t respect him. Perhaps that was it. He didn’t have ‘‘proper credentials.’’ Most of the sixteen members of the local board were women; many were on welfare. Nauman and the union didn’t think they were ‘‘professional’’ enough. Or, maybe they just weren’t white enough, perhaps that was the problem. In any case, a few days before, McCoy and the local board had decided to do something about it. They had met and made a list of the educators in the district who were the most hostile to community control. Nauman was one of them . . .

When the teachers tried to return to their classrooms, they were blocked by hundreds of community residents. On May 15, 300 police officers escorted the teachers back into the schools, breaking the blockade until the schools reopened in the fall of 1968, when the UFT led a series of citywide strikes to protest community control, shutting down New York’s public schools for 36 days. The strike ended in November of 1968 when the New York State Education Commissioner took control of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district and reinstated the dismissed teachers, but the damage was done; with Jews charging anti-Semitism and Blacks countering with charges of racism, the school fight fractured irrevocably the relationship between the two tribes who formed the vanguard of the revolution born at the nadir of the Great Depression.

While African Americans both in New York and around the country rallied behind the Brooklyn schools takeover, one high-profile Black leader opposed it: Bayard Rustin, the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, who denounced community control as "a giant hoax ... being perpetrated upon Black people by conservative and establishment' figures." He went on to elaborate:

(T)he leadership of the fight for the Negro to completely take over the schools in the ghetto is not the working poor ... it is not the proletariat.... This is a fight on the part of the educated Negro middle class to take over the schools ... not in the interest of Black children, or a better educational system, but in their own interest because they have nowhere to go economically.

The actor Colman Domingo last week earned an Oscar nomination for his sensitive portrayal of Rustin in the eponymous Netflix biopic. Produced by Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company, Rustin focuses on the period leading up to the March on Washington and depicts the icon as a courageous visionary who was ostracized by whites because he was Black, and by Blacks because he was gay. Curiously, Rustin’s public career continued nearly until his death in August of 1987 and yet the Netflix biopic makes no mention of his politics during the last quarter century of his life.

That is hardly a coincidence. Any honest interrogation of Rustin’s resume would reveal a sharp shift to the political right after the 1963 march and that Rustin was loathed by Black radicals and even white leftists, not because he was gay but because he was on the wrong side of every important issue. In 1965, the AFL-CIO’s deeply conservative President, George Meany, hired Rustin to head the A. Philip Randolph Institute, named for Rustin’s mentor. With the bag firmly in hand, Rusin went to work antagonizing every African American seemingly in sight.

Five years after he expressed his opposition to the takeover plan by Black and Puerto Rican parents in Brooklyn, Rustin would go on to tell disgruntled African American workers at the International Association of Machinists convention to "stop griping always that nobody has problems but you Black people" and that the privileges and positions of power white workers held in the union “were not on account of race."

The historian Robin Kelley noted that at the juncture when Rustin reprimanded the African American machinists, the international union had barred nonwhites for 60 of its 80 years.

And in proposing a “Freedom Budget” to dramatically increase social welfare spending, Rustin cut a deal with the Devil in muting his opposition to the Vietnam war, earning him the enmity of the Students for a Democratic Society and other organizations on the white Left that “regarded him as a turncoat and a Johnson puppet,’ wrote Podair in his Rustin biography. Continuing, Podair wrote:

Black nationalists, including members of SNCC and CORE, scorned him as a dupe of the white establishment. By this time as well, the economic pressures of the Vietnam War had made it impossible for the Johnson administration and Congress to even consider funding the Freedom Budget, and the rise of Black power and the explosion of civil disturbances in the nation’s Black communities had destroyed the political will of white Americans to pay for expensive antipoverty measures.

How isolated was Rustin? As one example, who struggled to maintain his own credibility with Blacks enthralled with Malcolm X and the more militant Black Power Movement, found his old friend problematic. Podair again:

Even King was keeping his distance. King also desired to end poverty in the United States, of course, but was much more willing than Rustin to articulate his demands from a position outside establishment political circles. By 1966 it was clear the two men were traveling in different directions. That year Rustin opposed King’s first venture into the North, a planned Chicago campaign for jobs and open housing, arguing that confronting the powerful Democratic political machine of Mayor Richard Daley was a mistake. In 1967 Rustin counseled King against taking a public stand against the war in Vietnam, advice the minister ignored. Rustin even criticized the more confrontational strategies of King’s 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, which shared the Freedom Budget’s antipoverty goals, but relied on the nonviolent direct action tactics that Rustin now questioned. The campaign’s planned sit-ins, he advised, would only alienate the Democratic legislators in whose hands the solution to America’s poverty problem lay. King never stopped listening to Rustin, but after 1965 he took his advice less and less. He believed that Rustin was a well-meaning man who had been seduced by establishment power and lost his way.

In 1966, Rustin collaborated with the CIA to rig the ballot in an election against the former President of the Dominican Republic, Juan Bosch, a socialist. Four years later, he called for the Pentagon to send military jets to support Israel in its fight against neighboring Arab states. And he denounced the Cubans and Soviet Union for their military support of Angola’s Marxist government while praising apartheid South Africa for backing the rebels. In a stunning display of either sophistry or ignorance, he wrote:

And if a South African force did intervene at the urging of black leaders and on the side of the forces that clearly represent the black majority in Angola, to counter a non-African army of Cubans ten times its size, by what standard of political judgment is this immoral?"

In a 1986 speech entitled "The New Niggers Are Gays" he anticipated the vilification of Black men by such intersectionalists such as Jemele Hill, who once tweeted that “straight Black men are the white men of the Black community. Rustin asserted:

Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new "niggers" are gays... It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change... The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people.

It is worth noting that in the Obamas' retelling of Rustin’s life, nearly all of the Black men depicted in the film were either violently homophobic–Adam Clayton Powell–or, like King, overly influenced by Black homophobes. Powell, however, contributed far more to African Americans’ independence movement than did Rustin, and what’s more, Rustin’s peers in the Black, gay community seem to have encountered very little resistance from straight Blacks. Baldwin wrote that he was widely accepted by Black activists, with Eldridge Cleaver being the only political figure to express any reservations about the writer’s sexuality. Similarly, Langston Hughes was widely embraced by Black activists despite his homosexuality, and Moranda Smith, a gay, Black labor organizer in North Carolina in the 1940s, was so wildly popular that her funeral was attended by thousands, including Paul Robeson.

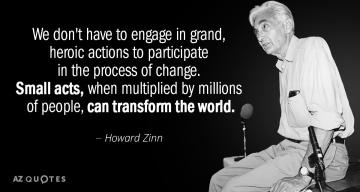

While Domingo was compelling in the lead role, Rustin is not art so much as counterrevolutionary agitprop, is intended to murder the radical Black polity that is the sine qua non of democratic transformation in the U.S. dating back to at least radical Reconstruction. And like his political heir, Barack Obama, Rustin was not a messianic figure but a menacing one, that threatens all African Americans who yearn to be free.

Jon Jeter is a former foreign correspondent for the Washington Post, Jon Jeter is the author of Flat Broke in the Free Market: How Globalization Fleeced Working People and the co-author of A Day Late and a Dollar Short: Dark Days and Bright Nights in Obama's Postracial America. His work can be found on Patreon as well as Black Republic Media .