In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Nick Nesbitt. Nesbitt is Professor of French and Italian at Princeton University. His book is The Price of Slavery: Capitalism and Revolution in the Caribbean.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

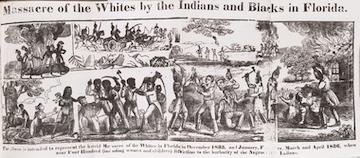

Nick Nesbitt: One way to understand the book is as an intervention in current debates on the nature of racial capitalism. Focusing on capitalist slavery in the Caribbean, the book argues that only by returning to Marx’s analysis of capitalism is it possible to grasp the nature of capitalist slavery as a social phenomenon—returning to Marx as did each of the Caribbean intellectual activists I discuss: CLR James, Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, Jacques Stephen Alexis. The book refuses to view modern, capitalist slavery as merely one among many (more or less exploitative) technical modes of producing ever more monetary wealth. Instead, it seeks to bring into question the historically contingent form of social relations we live in. This argument refuses, in other words, to take the generalized monetary exchange of commodities (capitalism) as self-evident and historically unsurpassable. I argue that the development and deployment of racial ideologies and capitalist production processes (including slavery) necessarily occurs within a governing framework of social relations, which Marx called the capitalist social form. In place of a vulgar Marxist theory of exploitation-as-personal oppression, Marx himself precisely defines concrete capitalist slave labor as a form of fixed, constant capital, and then demonstrates, unequivocally, that while slave labor contributes to the production of commodities (sugar, cotton) that can capture a profit upon market sale, it does so without that uncommodified slave labor producing surplus value. Finally, amid the current proliferation of fake news, the post-Trump racist malaise and democratic dysfunction, and the abysmal predominance of social media as worldview producer, to undertake such a close, postcolonial reading of Marx’s Capital has the further benefit of giving the reader (and here I include myself) an understanding of what it means irrefutably to prove a claim (in this case, the essential nature of capitalist slavery). Marx did not simply voice “viewpoints,” and “perspectives.” In Capital, he carefully shows the reader, step by step, point by point, what must be the essential characteristics of any society that is characterized by the general predominance of commodities and commodified social relations (including capitalist slavery).

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

I hope readers will come away with a deepened understanding and appreciation: of the nature of capitalism and the fundamental place of slavery within it; of the fundamental importance of Marx’s analysis of capitalism for the great black militant thinkers of the Caribbean; of the extraordinary and contemporary genius of Marx’s unfinished masterpiece, Capital, along with, as W.E.B. Dubois repeatedly tells us, its absolutely crucial importance for grasping the true nature of racial capitalism and slavery. Only with such critical reflection, I would argue, can we hope adequately to grasp the essential place of racial discourse and violence within the capitalist social form. In the 1940s, CLR James held regular reading groups to discuss the importance of Hegel’s Logic for contemporary, anticolonial and anticapitalist militancy; today, as we collectively live through the experiences of Occupy Wall Street, of the murder of George Floyd and so many others, of Black Lives Matter, it is essential to understand the necessity that governs these and so many other horrible events, their absolute necessity, that is to say, for the capitalist social form. Only then can we hope to grasp the limits of the latter, and to imagine more just social forms that might lie beyond it.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

I hope that some readers (and here too I include myself) might unlearn the all-too-understandable prejudice that our immediate lived experience of violence and oppression is sufficient in itself to orient a militant critique and response to that injustice. The lesson I take from the great thinkers of the black radical tradition—Toussaint Louverture, Vastey, WEB Dubois, Aimé Césaire, Suzanne Césaire, CLR James, Frantz Fanon, and so many others—is to seek out and steal whatever theoretical tools may be lying around, and to critically adapt them to our own needs. Whether the French Jacobin or African Mande Declarations of Human Rights, Hegel, Spinoza, Marx, or any other penetrating resource, there can be no arbitrary limits, racial or otherwise, to the materials of critical thought.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

All the great figures of the black radical tradition I’ve already mentioned, categorically including Marx himself, as for example in his vehement critique of American slavery and vocal support for its absolute abolition in 1865 in his letters to Lincoln and elsewhere. Behind them all, however, lies hidden that great heretic, the inventor of ideology critique, of the critique of the illusory nature of unreflected lived experience, of the systematic critique of racism and antisemitism, a thinker who did not merely take a stand against all the violence, injustice, and illusions of his world, as have so many others, but who in response developed in his most extraordinary work of heresy, the Ethics—a book that was immediately banned but had an extraordinary underground, subterranean influence for centuries—the means to understand and to overcome all our illusions and injustices, a critical methodology to bring our powers of thought and freedom to their utmost human degree. I’m thinking of course of the heretical Jew of Amsterdam, Baruch de Spinoza.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

To imagine new worlds requires a clear and adequate understanding of the limits of the one we actually live in. What is the essential nature of racial discourse and violence within the capitalist social form, a social form dedicated only to the abstract goal of the unlimited accumulation of surplus value? How did plantation slavery contribute, in theoretical terms, to the historical accumulation of surplus value within capitalism, if, by definition, such uncommodified labor is incapable of creating surplus value? It is no accident that following his initial political interventions of the 1840s, Marx dedicated the last three decades of his life to the structural, theoretical analysis of the capitalist social form. In fact, it is precisely this profound theoretical understanding that then allowed him immediately and fully to understand the political and social radicality of situated events as they unfolded, such as the American Civil war or the 1871 French Civil War and Commune. This insight allowed him to articulate in the moment an amply progressive political orientation, and to show how such situated events pointed beyond the limits of the capitalist social form, limits that he, arguably better than any thinker before or since, grasped in their concrete and terribly real necessity. If we do indeed still live today in the capitalist social form—and who would deny it?—it is only by standing on the shoulders of the great thinkers of the past, refusing all sectarian forms of theoretico-racial prejudice, by seeking, always critically, to look at the present through the theoretical lenses that they so finely polished, that we may hope to understand, to underscore, and to undermine the terrible necessities that govern our current existence.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.

![DOCUMENT: An Act for the Abolition of Slavery [and for Compensating White Slaveowners], 1833](/sites/default/files/styles/nc_thumb/public/2022-03/slavery%203.png.jpeg?itok=10ZbOZCQ)