In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is David Lester. Lester is the co-creator of the graphic novels The Listener and the award-winning 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike. His book, edited by Paul Buhle and Marcus Rediker, is Prophet Against Slavery.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

David Lester: One might think that writing and drawing Prophet Against Slavery, a graphic novel about an historical character from 300 years ago, could be tough to make relevant to a modern audience. But the story of Benjamin Lay and his fight for the abolition of all slavery is remarkably contemporary. The lineage of all progressive social movements can be traced back to the anti-slavery movement which was most certainly the very first activist movement in North America.

Benjamin Lay was a dwarf and a hunchback who came from humble origins. He received no education, yet developed into a revolutionary, a radical American Quaker. A vegetarian and animal rights activist, he would not wear clothes made from animals as their production might have caused suffering. His empathy, perhaps shaped by his low social standing in society, is a key factor to his radicalism.

Because of the expressive nature of hands, in Prophet Against Slavery I repeatedly drew a visual motif of clasped or touching hands, all as a way of showing empathy, friendship, love, solidarity, comradeship, and working collectively for a greater good.

Lay focused on stopping the Quaker hierarchy from owning and selling the slaves but he also wanted to end this practice everywhere. In the only book Lay wrote, he warned that if slavery was not ended immediately, the legacy of racism would profoundly haunt America. His prediction was not wrong and it explains where America finds itself in the 21st century.

In the 18th century it was common for Europeans to consider slavery acceptable. This social thought process continues today with the institutional oppression that we see in police departments, political parties and government bodies.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

The battle for social justice is not always a linear narrative. It is far messier, it is far more abstract, and what appears to be defeat at one moment is simply part of a longer struggle on the road to social progress and victory.

Benjamin Lay’s dogged example of speaking truth to power and of using guerrilla theatre in his protests should be a source of great inspiration for activists. Historical graphic novels like Prophet Against Slavery are part of that struggle. The tradition of using art and text in social justice work has a long history. By using the graphic novel form to present Lay’s radical life in an engaging way, Prophet Against Slavery has perhaps demonstrated a way forward for activist art.

Graphic novels have the power to communicate in ways that traditional history books do not. They can remove barriers from potential readers who find politics or history boring, or intimidating. In the case of wordless graphic novels, readers of all backgrounds, education, and language can engage.

A while ago I spoke to high school teachers who said that they are finding students are increasingly unable to read longer texts, like books. Graphic novels are now fundamental tools in the process of education. Remember, these students will be the future activists, the future Benjamin Lays.

In Prophet Against Slavery, I used visual motifs of repetition. I wanted to mirror how repetition is a fundamental part of political activism. The struggle for social change can be a relentless one, often a tiring slog with the sense that the same things are said and done over and over again. But this is the process of change.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

In Prophet Against Slavery, Benjamin Lay makes it clear that oppressing any living creature is abhorrent. His life was dedicated to dismantling the ideology of oppression and the complicity that oppression is fueled by. He would attend Quaker meetings and dramatically point out slave owners in the congregation, “No man or woman should pretend to preach the truth in our meetings, while they live the lie of slave-keeping. America is a selfish, sordid, greedy, covetous, earthly minded people as any in the world.” For his outbursts, Lay would be dragged out of the meeting hall, with his shouts of “No Justice! No Peace!” echoing.

Lay also attacked the international use of the enslaved to make consumer products, “The labor of slaves makes your tobacco. Be courageous and end thy sinful complicity with slavery.” It is incredible to think that 300 years ago someone was making the connection between the goods we buy and under what conditions they are manufactured. To push his point, Lay advocated the use of boycotts, “I strike a blow against the tyrants who torture those in the Caribbean who produce the sugar to sweeten your tea. One must never consume goods born of oppression.”

One struggle in drawing comics is to convincingly convey movement with two-dimensional drawings. Because Benjamin Lay's activism was so physical, I couldn't always use the traditional methods of drawing. In the scene of Lay's guerrilla theater action against exploitation of workers, where he smashes tea cups in a city square, I sketched in a raw, you-are-there quality, and spattered paint on to the sketches, further indicating a sense of movement and disarray.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

The over-arching concern of my life has been the belief in the power of art to play an important role in achieving progressive social change. So my heroes have generally come from the arts, Paul Robeson, Kathe Kollwitz, Phil Ochs, John Hearfield, Emma Goldman, Nina Simone, and James Baldwin. They used their work to tell social and political stories while exhibiting a great sensitivity and empathy.

This combination of art and politics educated me about the world. It was fundamental to my choices in life, to what was important to me, to how I wanted to spend my time on earth.

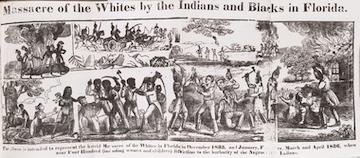

For the drawings of the enslaved and slavery in this graphic novel, I generally used a rough style, typified by sketches from the eighteenth century. I was also trying to achieve the effect of the drawings being done in the moment, as a witness to slavery. I wanted that sense reflected by having an unfinished quality to the drawings. The unfinished quality metaphorically shows that these are lives in suspension because of the cruelty of slavery. Slavery is not who these humans are; it is what they have been forced to be through inhumanity. In some cases, such as the double-page spread depicting the horrors of slavery, I resorted to extreme drawing methods, using a knife to directly cut into the paper and wet paint in order to achieve a sense of chaos and brutality.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

It is vital that progressive people offer their narrative to history because we know that the right wing, anti-democratic forces, despots, fascists, racists, and misogynists often crave legitimacy through history. Witness the monuments to the confederacy in the American South. As citizens we need to comprehend our past in order to have a sophisticated understanding of our present and lead us to imagine new worlds.

In Prophet Against Slavery I used the art as an element in imagining a new world, for example Benjamin Lay’s height became a visual dynamic. As I illustrated him during his confrontations with the Quaker establishment I emphasized his dwarfism but as Lay's arguments gained the moral and political high ground, I used close-ups of his face to show that the dynamic had shifted. By using close-ups and tilting the angle of his head, metaphorically, it becomes Lay who is looking down upon the Quaker slave-owners and their moral failings and hypocrisy.

Benjamin Lay was already 55 when he carried out one of his most extraordinary acts of guerilla theatre in the opening of my book. It is his longevity as an activist, exhibiting stamina, fortitude and integrity in the face of the cruelties observed against his fellow humans that he imagined a world without slavery. He was a revolutionary who wanted to turn the world upside down. He did, but that work is not finished.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.