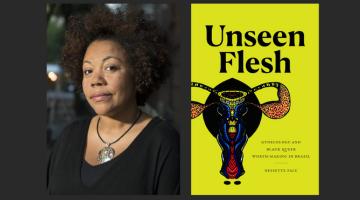

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Kemi Adeyemi. Adeyemi is an Associate Professor of Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies and Director of The Black Embodiments Studio at the University of Washington. Her book is Feels Right: Black Queer Women and the Politics of Partying in Chicago.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Kemi Adeyemi: This book is fundamentally about the ways that people create space in the midst of, and sometimes in spite of, the protocols of urban development that govern and shape our opportunities to live, work, and play. It focuses on how the economic imperatives of neoliberalism, in particular, organize the physical landscapes of cities and impact our social and cultural practices of inhabiting them.

I’m specifically interested in showing us how black queer women use their cultural practices—of organizing, DJing, and dancing at parties—to reveal and contest how cities are organized to maximize profits over people. In the intimate spaces of the dance floor, black queer women's practices show us how individuals and collectives can always push against and exceed the restrictions that neoliberalism places upon us, especially the ways that neoliberalism promotes and rewards a kind of extractive and exploitative individualism. Every time black queer women get on the dance floor, they’re practicing modes of producing collective power that we should look to for guidance.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

I hope that people will take the dance floor seriously as a site of producing politics, a site where the politics of inhabiting community are really materially engaged in the ways that we put our bodies in direct conversation with other people’s bodies.

This project documents political life as a really intimate and vulnerable process—a process where the theories that we have for activating in our cities come to a head in the methods that we have for being in space with one another. And oftentimes, the gaps between theory and practice really surface in how we approach the dance floor, what we do on the dance floor, what we take away from the dance floor. So I hope that the book provides people an opportunity to think about the many scales at which their political beliefs and practices take place, and to frankly give them some more tools for understanding themselves as inventive political agents whose modes of critique are just as embedded in the language as in the movements they inhabit on the dance floor.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

This is a tough question! I'm trying to dismantle the idea that black queer women do not have a stake in the production of space, to call upon Katherine McKittrick’s work. And that is an idea that emerges in this sheer absence of black queer women in larger studies of black life, queer life, women's lives.

It is also an idea that emerges in the ways that we ignore or avoid black queer women's experiences when we imagine more ethical and just ways of living, in the city and otherwise. When black queer women do appear in the academy or in political movements, it is often as a kind of metaphor or stand-in whose presence and/or values we simply use to identify our own liberal or progressive politics within and beyond the academy (e.g. we’re skilled at saying things like “I’m an intersectional feminist” or “I care about the LGBTQ community” as part of our larger self-definition of our liberalism or our progressivism). But we rarely ask black queer women about their political lives, let alone use their words and experiences as the framework with which we might forge new pathways into critical thinking.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

First, Black queer women who gather on and around the dance floor. In saying that I mean to honor the fact that the people we think and write about are already doing the work, we in the academy are just framing and interpreting their labor for different audiences. The best case scenario is that our critical and creative practices within the academy complement the work of the people we think with beyond the it.

Second, I am most inspired by people who think philosophically about the production of identity as a physical, phenomenological process that is shaped in close conversation with political economic conditions—including a range of thinkers from James Baldwin, Erving Goffman, Frantz Fanon, June Jordan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jayna Brown, Hagar Kotef, Adrienne Brown, John L. Jackson, and others. I’m down to read and think about any thinker and any discipline that helps me think in more interesting and creative ways.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

Hanif Abduraqqib, A Little Devil in America: In Praise of Black Performance

Adrienne Brown, The Black Skyscraper: Architecture and the Perception of Race

My training is in performance studies and I am very interested in the relationships between race, movement, and space—and, more specifically, about the ways that racialized gender is made legible through and as particular capacities for movement within and across particular spaces. These two texts are part of a welcome trend of critical and close readings of the small gestures through which race, sexuality, and gender are made legible (and consequential) in the material gestures and structures of everyday life.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.