As part of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum, we interview scholars about a recent article they’ve written for either an academic journal or popular publication. We ask these scholars to discuss their article, as well as some of the books that have most influenced them.

This week’s featured scholars are Adam Bledsoe and Willie Wright. Bledsoe is an Assistant Professor at the University of Minnesota. Wright is an Assistant Professor at the University of Florida. Their article is “The Anti-Blackness of Global Capital.”

Statement in Memory of Glen Ford, By Adam Bledsoe and Willie Wright:

As we thought through the questions posed to us, we were reminded of how we both came to engage with BAR, through an invitation from Glen Ford. Brother Ford invited us on separate occasions to speak on Black Agenda Radio about different aspects of our work. Personally, we always found him to be a politically and principally astute observer of the black world who never wavered in challenging those whom he believed were of detriment to the black diaspora - charisma be damned. Moreover, he was an insightful and widely-read thinker who was also incredibly generous in his engagements with our work as young scholars. His breadth of knowledge and clear political commitments to Black Radical politics remain inspirational to us and his example will continue to orient us in our own work. He will always be an important political and intellectual role model for us and we believe other scholars and activists can learn much from his example.

He is missed.

Roberto Sirvent: In your article, you draw on the concept of “anti-Blackness” as articulated by theorists engaging with Afro-pessimism. When it comes to understanding global capital, why is “anti-Blackness” a more useful analytic than “racism” or “white supremacy”?

Adam Bledsoe: Anti-Blackness is a unique logic that cannot be conflated with the general term “racism” nor with the more specific idea of “white supremacy.” Racism is a process by which imposed “racial” hierarchies have negative, concrete effects for racialized populations, whereas white supremacy is the assumed superiority of European and Euro-descendant populations. Anti-Blackness intersects with both of these, but must be understood in terms specific to Diasporic Black experiences. Anti-Blackness is defined by the assumption that Afro-descendant populations have no legitimate claims to self or space. In an anti-Black world, individual Black people, as well as the locations they inhabit, are deemed inhuman and always open to the prerogative of those deemed more human. This assumed inhumanity and a-spatiality (the condition of being “ungeographic” discussed below) has profoundly destabilizing effects for claims of redress and reparation, as anti-Blackness makes claims of sovereignty, nativity, violation, etc. tenuous for Diasporic populations. While racism and subjection to white supremacy is the purview of many racialized groups, conceptually lacking a claim to self and space is specific to Afro-descendant populations. Attention to the concrete effects of anti-Blackness is vital to understanding Black populations’ experiences under capitalism, as the assumption of Black inhumanity and placelessness are central to capitalism reproducing itself.

Willie Wright: As a society - and as a society of intellectuals - social scientific conceptualizations of racism and white supremacy have dominated our policies, our politics, and our desires for redress. Scholars operating within the frame of Afropessimism tilt the mirror, so to speak. This is done through their centering of anti-Blackness as a governing logic, their unyielding belief in the endurance of chattel slavery and the role of the contemporary Black subject (as slave) within our post-modern society. Also, a number of these scholars do so through a psychoanalytic versus, say, a sociological approach. For some it may be difficult to be diagnosed as inhabiting a slave subjectivity when we have, presumably, come so far. Perhaps it is even more challenging for those with a modicum (or more) of privilege to accept such an assignment. It does not help the case for Afropessimism that its most prominent protagonists, like a therapist, do not offer solutions to remediating this damned world they’ve thrust before us.

Nevertheless, I believe it is a useful analytic for seeing the world: how it was made, how it is sustained, and the role of varying subjects therein. For some of its critics, Afropessimism is injurious because it appears to encourage political apathy and offers no recourse to the oppressions mounted against us. I, however, read it as a veiled critique of the practice of academic writing. The decision to engage in narrative restraint[i] is a conscious one – though it goes against the standard practice of publication, whereby the reader is provided a concluding chapter with recommendations for redress. But what is redress when you believe the world is born of antagonism and not of conflict? Second, when it comes to the work of Frank B. Wilderson III, rife within Incognegro and Afropessimism are stories of his education by, and participation with, movement organizations (e.g., the Black Panther Party and Mikeze we Sizwe). Therefore, one might presume that he believes any answer that would lead towards an end of the world (i.e., civil society) will not be conceived within the works of a lone academic, but amongst political organizations.

I believe sustained and serious engagement with (not necessarily the adoption of) this concept can be a boon to Black Studies and the practice of Black study. If engaged genuinely, there could emerge new forms of thought within Black Studies. This is me thinking about intra-disciplinarity dialectically, using Afropessimism as an enzyme for the expansion of our field. We are at a watershed moment in Black Studies, with many programs and departments having celebrated their 50th anniversary and the fact that scholars across a variety of fields have taken the charge of furthering the discipline. No matter how Afropessimism is engaged, henceforth, it too is a part of this history. My desire is that it will be for the betterment of the Black Diaspora and not merely a catalyst for academic jousts.

Part of your goal, you write, is “to explicate the ways in which capitalism is actually dependent on anti-Blackness to realize itself, instead of understanding anti-Black racism as a secondary effect of the economy or a phenomenon that emerges periodically.” How does this approach differ from most (non-Black) Marxist approaches found in both the academy and organizing spaces?

AB: Our approach seeks to challenge the universality of concepts like “the working class” and the assumption that class struggle can address the primary antagonisms faced by the global masses. Without discounting the necessity of deep analyses about, critiques of, and alternatives to, capitalism, our approach insists that there are logics that exist prior to, and in excess of, capitalist exploitation. Many neo-Marxist approaches treat race as a secondary phenomenon that capitalists machinate to prevent the working-class from creating an inclusive identity. We argue, however, that anti-Blackness does not emerge as an outgrowth of capitalism, even if capitalists and capitalist relations have drawn on anti-Blackness historically. Rather, anti-Blackness exists as a constitutive element of notions of self and being in Euro-modernity and capitalism draws on the logic of anti-Blackness to realize itself. In making this argument we see ourselves in conversation with Cedric Robinson’s argument in Black Marxism that capitalism employs racialized societal divisions as a means to reproduce itself. While much of the globe remains dominated by capitalism, anti-Blackness uniquely positions Black populations both conceptually and concretely in the world. We cannot appreciate this position and its real-world effects (as well as how capitalism is able to draw on anti-Blackness) if we subsume the position of Diasporic populations under a supposedly universal “worker” identity. Black people are not the only ones facing the predations of capitalism; however, they do experience capitalism and Euro-modern notions of rationality in ways that are distinct from other exploited, dominated groups. Ignoring the particularity of Diasporic populations’ relationship to capitalism and Euro-modernity contributes (even if unintentionally) to reinforcing the assumption of Black a-spatiality, which is, unfortunately, both our societal default and a central component of global capitalism.

WW: Building on Adam’s point, I would like to add that an attunement to the primacy of anti-Blackness as a world-and human-making project, requires that we grapple with the nature and place of Black humanity within, but not as a full subject of, civil society. For me, this is a question of obfuscation versus elucidation. What kinds of questions and clarifications might we come to when we begin with the assumption of anti-Blackness (not capitalist relations of production) as the foundation of the modern world and the modern subject-as-worker? Hence, we center it in favor of a purely class analysis, or one refracted by race. I would like to offer an elucidatory example. Common parlance suggests that neoliberalism emerged as a post-Keynesian state project in the 1970s and solidified in the 1980s. Decades later, we bear witness to the brutalities of state-led austerity across nations without recourse to the particularities of the exploitations associated with these policies. It often stated, within these discussions, that all other exploitative relations (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia) are but tributaries of the macro-level processes of (finance) capital. We believe that incorporating anti-Blackness into conversations around neoliberalism, unveils “a neoliberalism of a long durée.” Accounting for this ante-austerity (i.e., anti-Blackness) regardless of a nation’s political economy (e.g., Keynesianism v. Socialism v. Neoliberalism) brings to the fore how across geo-time value has been created through the socially necessary labor of extraction-by-force – whether through enslavement, Jim Crow, de facto segregation, or vigilante violence. And so, part of our work is to illustrate anti-Blackness as a global condition that has specific spatial expressions.

Citing Katherine McKittrick, you discuss how Black communities are deemed “ungeographic” when in comes to dominant views of space and place. What is meant by the term “ungeographic”? And can you share with readers how you became interested in the field of Black geographies, and why you find it important for analyzing structures of domination like anti-Blackness and capitalism?

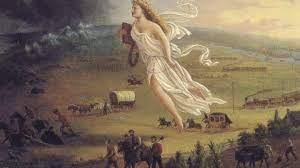

AB: If geography is the process of analyzing our physical world and how it is constructed, then geography is also a practice by which we understand, represent, and, ultimately, create the worlds in which we live. This process may sound straightforward, but in the modern world only certain practices (those deemed “rational”) carried out by certain populations (those deemed “human”) are treated as legitimate acts of knowing, representing, and creating space. In short, only specific actors are deemed “geographic.” Chattel slavery and its afterlives have historically and currently created power structures that deny the human, and by association, geographic capacity of Afro-Diasporic populations. That is to say, Black populations are viewed and treated by dominant actors and institutions as if they do not have the potential to adequately know, represent, or create space–they are “ungeographic” (or a-spatial). This leads to the locations associated with Blackness (from the scale of the body to that of the nation-state) being treated as fundamentally “unhallowed” sites, absent the recognition afforded locations associated with human beings. This remains the case even when Afro-descendant groups seemingly master dominant, “rational” ways of comporting themselves in the world.

Black Geographies, as a subfield that merges critical geography with Black Studies, is an approach that we have engaged since graduate school. In bringing together bodies of work that analyze the relations that make up the world we live in, along with work attentive to the specificities of Black Diasporic experiences, Black Geographies demands that we take seriously how the lived realities of Black populations shape the spaces we move in and have a hand in creating. If Blackness and anti-Blackness are constitutive elements of our world, then they are also central to phenomena like capitalism. Any responsible critique of, and proposed alternative to, capitalism must engage with Black Geographies.

WW: Black Geographies takes those deemed ungeographic or a-spatial and highlights how these communities engage space and create place, oftentimes, in unorthodox but no less significant ways. As Katherine McKittrick’s work suggests, the infrastructures of civil society (i.e., urban/regional planning) are material extensions of plantation logics. As descendants of enslaved Africans, our cartographic reasoning is often viewed as irrational. In other words, the rhythms of our life do not fit – even when engaging in mimicry (e.g., homeownership) – within society’s conceptions of development, place, and belonging. Lately, I have been moved by news reports of differential home appraisals between Black and white homeowners, despite existing in similar markets and communities. If this legible spatial form of civility is devalued – be it intentional or libidinal – then, what of ineligible spatial relations? This question is of particular importance within a neoliberal age in which capital is expanding rapidly via urban and rural land grabs. This, then, takes us back to your previous question. We believe, when it comes to Black folk, that it is not one’s middle-class status, nor one’s working-class relations that are the cause, prima facie, of these devaluations or the various dispossessions endured across the Diaspora. There is something within the underside[ii] of class and capital that results in the contributions of Black communities –and here I am speaking of intellectual and geographic contributions – being overlooked and outright omitted from the annals of history and the planning of regions. This is where Black geographies intercedes. A Black geographies approach acknowledges that embedded within the particulars of Black social life, are alternate ways of knowing and being within this world. Black geographies is the synthesizing of the analogs of Black social life into a spatial analytic and methodological approach to the study of Black life.

In another co-authored journal article, “The Pluralities of Black Geographies,” you write about the Black Panthers’ commitment to community-based self defense. What can Black autonomous, anarchist, or maroon communities (especially outside the U.S.) teach us about the importance of communal self-defense for today’s collective struggles against injustice?

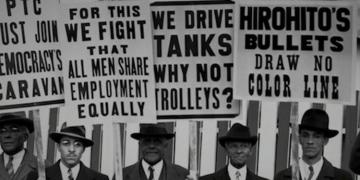

AB and WW: The individual and collective defense of Black bodies and Black spaces is present in countless instances of Black Diasporic struggle. Unfortunately, Black and non-Black people remain, generally, uneducated regarding the rich histories and continued existence of Black self-defense. Black groups’ willingness and proficiency in defending themselves is either treated as a masculinist, exotic oddity (a la the Black Panthers); tragic hubris (a la Nat Turner); or ignored altogether. As Black people, we owe it to ourselves and to the global struggle against anti-Blackness and capitalism to recognize the role Black self-defense played in Black political gains throughout history. Outside the U.S., examples like the Haitian Revolution; armed maroon struggles in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Suriname, Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola, among others; the guerrilla tactics of the Afro-Brazilian communist insurgent Carlos Marighella; and the activities of Afro-Venezuelan guerrillas in the Partido Revolucionario Venezolano (among many, many others) are central to understanding present-day expressions of Black territory, culture, and political demands. Inside the U.S., Black self-defense made nationally-transformative moments like Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Black Power Movement possible, while also having a prominent role in lesser-known episodes like U.S.-based marronage. While someone could argue, perhaps, that self-defense was not necessary in the above-mentioned examples, the fact of the matter is that self-defense did occur in these historic instances and helped create the possibility for the constructive programs of these different movements. Indeed, the destabilizing effects of anti-Blackness make Black self-defense (whether armed, unarmed, or environmental) an indispensable component of Black political struggle around the world.

A lot of organizers, artists, and academics can often point to books that helped radicalize them. Are there any books that radicalized you? How so?

AB: The three books that affected me the most in my intellectual and political formation were The Huey P. Newton Reader, Black Reconstruction (W.E.B. Du Bois), and Red, White & Black (Frank Wilderson). I read all three books in graduate school and all three pushed and inspired me in different ways. Black Reconstruction gave me an appreciation for the potentiality of collective Black struggle and freedom drives and also laid bare the willingness of the postbellum U.S., as a political and social entity, to deny Black humanity and citizenship. The Huey Newton Reader was a powerful collection of the evolving thoughts of someone who sought to organize urban Black communities to autonomously create the world they wanted to live in. I was in awe of Huey’s capabilities as a thinker and organizer and the conviction with which the women and men of the Black Panther Party threw themselves into revolution. Red, White & Black was my introduction to Afro-pessimism and forced me to really grapple with the specificities of Black populations’ structural position in the world. Some people argue that Afro-pessimism encourages political apathy, but I read Wilderson, the other Afro-pessimists, and their intellectual progenitors as offering a sober starting point for radical politics.

WW: I feel as though I was a late bloomer to the joys of reading. However, when I began reading of my own accord, what I learned rather quickly is that I have a deep appreciation for autobiographies. My particular interest is how people have charted their lives and overcome obstacles. Texts that I can recall were Mark Mathabane’s Kaffir Boy, and perhaps, Anne Moody’s Coming of Age in Mississippi. The first is about a Black child growing up in Apartheid South Africa who makes it out through his success as a tennis player. You’re given a sense of the overwhelming oppression that looms about but not the in-depth knowledge of those organizing against it. Moody revisits her coming of age and political maturation during the Civil Rights Movements in Mississippi. I would not say that either book radicalized me, but they did begin to open my mind to Black struggles. Other texts that were instrumental in my development are The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Ivan van Sertima’s They Came Before Columbus, Huey Newton’s Revolutionary Suicide, Elaine Brown’s A Taste of Power, and Octavia Butler’s Exogenesis Trilogy.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these works in your future scholarship?

AB: One of my advisees encouraged me to read The Common Wind by Julius Scott. It was a great suggestion and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. I would recommend it to anyone interested in the history of the Americas. I will be using it in my Black Geographies and Latin American Geography classes to help students think about how Diasporic populations maintain communication and contact with each other; and how narratives and examples of freedom struggles occurring in one location can be taken and interpreted across a variety of contexts.

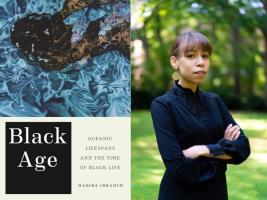

WW: I’ll give two published and two unpublished works. I found Joy White’s Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City to be a useful read. Some texts I am looking forward to engaging are Jovan Lewis’ Scammers’ Yard: The Crime of Black Repair in Jamaica, Camilla Hawthorne’s Contesting Race and Citizenship: Youth Politics in the Black Mediterranean (forthcoming) and Orisanmi Burton’s Tip of the Spear: The Long Attica Rebellion and Prison Pacification in the Empire State (forthcoming). The first text will likely be instrumental as I think further about (anti)Black urbanity. As for the latter, it is not yet discernible how they will influence my thinking.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.

[i] Clearly, this is a reference to Saidiya Hartman’s methodological approach – introduced in “Venus in Two Acts” – to writing a history of the enslaved.

[ii] This is a reference to Clyde Woods and Katherine McKittrick’s introduction to Black Geographies and the Politics of Place. There they describe Black social life as being within the “underside” of civil society, and subsequently, as the foundation for an upright state. It is also a nod to Saskia Sassen’s Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy, wherein she draws out the post-Keynesian “subterranean” processes lurking below geopolitical and politic-economic explanations of the brutalities suffered by human-environment ecosystems throughout the world today.