In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Debra Thompson. Thompson is the Canada Research Chair in Racial Inequality in Democratic Societies and Associate Professor of Political Science at McGill University. Her book is The Long Road Home: On Blackness and Belonging.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Debra Thompson: If there’s one truism about American history, it’s that racial progress is always, always shadowed by a disproportionate white backlash. I think that right now, we are at the beginning – not the middle, and nowhere near the end – of the most recent iteration of this pattern. Many people believed that the George Floyd rebellions were a turning point. Some in the media even called it a “racial reckoning,” four hundred years in the making. One of contributions of The Long Road Home is that it helps to situate the moment we’re currently in – the third year of a global pandemic that has killed millions; two years out from the largest mass uprisings for racial justice we’ve ever seen; in the midst of the ongoing war on critical race theory; in the aftermath of the downfall of Roe v. Wade – and put this moment in the context of the recent past. The book begins with my ancestor’s escape from slavery (because we cannot ignore or wish away the many, varied, and haunting afterlives of slavery) but most of the text focuses more narrowly all that has happened in the past decade. From the post-racial rhetoric of the Obama era to the extreme political polarization after the rise of the Tea Party, the emergence of Black Lives Matter, the overt white nationalism and xenophobia of the Trump era, the George Floyd rebellions, and now, the current moment of both uncertainty and unrealized possibility.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

I don’t think there’s much that I can tell activists and organizers that they don’t already know! They’re the ones doing the on-the-ground work, often better and with deeper knowledge than folks like me. But, if there are people out there looking for a good introduction to vast bodies of academic literature in the social sciences on Black political and social life, Black-Indigenous solidarities, migration studies, the politics of race in comparative context, the determinants of racial resentment, the manifestation of systemic racism, and the relationship between race and the development of key political institutions such as federalism and the constitution, then this book provides that. It also delves into some of the most important and longstanding questions that have animated African American political thought for centuries: What is the cause of racial domination and how does it intersection with class, nation, gender, and sexuality? Who are our friends, who are our enemies, and can we – should we – form coalitions with other oppressed peoples? Are white people trustworthy as allies, and is it possible to convince them to abandon racism? What is the American Dream, and can Black people achieve it? Finally, it’s a deeply personal story of how I came to understand, value, and believe in more radical, abolitionist political commitments. I hope that it will resonate not only with those folks who have walked a similar path, but also with those who are perhaps at the very beginning of their own journey to better understand the meaning of race and the stubborn persistence of racism, who want to do and be better but are scared of making mistakes along the way, and who believe, down deep, that we can still change the world.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

I’ve had a decade-long obsession with American exceptionalism. Americans often think of their country as exceptional – it’s one of the world’s oldest democracies, the birthplace of revolutionary freedom, the only remaining superpower, the last line of defense in a world threatened by dictators and demagogues. But for African Americans, the United States has never been the beacon of freedom it claims to be. American racism is all the more tragic precisely because it exists alongside but in direct contradiction with the American Dream. And to those of us who observe American history in the making from abroad, the United States is only exceptional in terms of how utterly, unforgivingly, uncompromisingly racist it is. This idea of American racial exceptionalism is particularly powerful in Canada. Canadians understand American racism as real and morally repulsive, and often use the prevalence of American racism to deny the existence of Canadian racism. Canadians are righteously indignant about anti-Black racism in the United States, and fallaciously defensive when the perpetrators are the “us” and not the “them” – this cognitive dissonance is, in and of itself, a peculiarly Canadian form of racism.

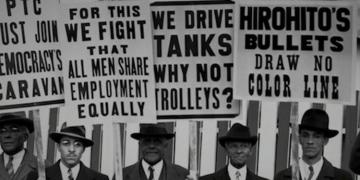

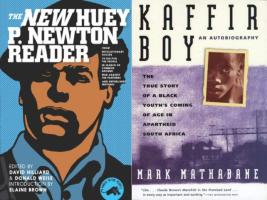

One of the central ideas of The Long Road Home is that there is an innate value in the exploration of Blackness, belonging, and the broader politics of race in the United States and Canada not in contrast, but rather in relation to one another. Others (no shade intended) have decided that racism in the United States is only comparable to Nazi Germany or South African apartheid, but I want to suggest that while extreme cases have much to tell us, so, too, do unsuspecting ones. More to the point, ideas and inspiration, people and profits, goods and grievances have crossed the border for centuries. So have Black freedom dreams, which were truly cultivated in the possibility that Canada could be a sanctuary from American slavery, and strengthened in the hope that a transnational understanding of Black identity could be a bulwark against global white supremacy.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

The book grapples with what it really means to be part of the African diaspora in the United States, which is often situated as the undisputed core of Black cultural identity, and in Canada, where Black populations are kind of the diaspora of the diaspora. In this way, the book is part of a long tradition of Black internationalism and a common, globally-oriented political project of demanding and defending Black humanity in spite of the continuing aftershocks of the devastating commodification and ruinous violence of the transatlantic slave trade. The Long Road Home understands diasporic ways of being as multiple, overlapping, and dissonant. So, to share a diasporic identity doesn’t mean that all experiences within the Black diaspora are interchangeable; rather, disagreement and disavowal, altercation and ambivalence are part of conceptual, global history of Blackness.

Much like the Black internationalism and post-colonial movements of the past and present, the book extracts the shared quest for freedom in the far-flung edges of the African diaspora not as fictitious or forced kinship connections, but as dissonant, always complicated, sometimes even contradictory freedom-seeking intimacy among strangers. Like those who came before me, I try to think through the ways that closeness and connections exist alongside the fractures, fissures, and frictions that shape the different parts of the global Blackness, and try to find nuance in the translations, transcriptions, and transferences of identities and political aspirations from one place to the next, from one time to another, including those times we have yet to imagine.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

There’s so much great work coming out, especially for folks interested in abolition! But the two books that I’ve been thinking the most about lately are Katherine McKittrick’s Dear Science and Other Stories (Duke University Press, 2021) and Melvin Rogers and Jack Turner’s edited volume, African American Political Thought: A Collected History (University of Chicago Press, 2021).

McKittrick’s book is just beautiful. It’s a thought-provoking, creative, unique extrapolation of Black and anticolonial methodologies. There were some moments while writing my book when I wasn’t convinced that I had the right to preach to anyone about Blackness and belonging, given that it has taken me so long to develop this (even now, incomplete) understanding of Black diasporic politics. And it was through reading McKittrick that I came to understand the necessity of storytelling, repetition, collaboration, imprecision, poetry, friendship, uncertainty, and flux. She gave me permission not to know all the answers and to share my unknowingness with others. It’s an incredible gift and the text has challenged me to think differently about how to think.

Rogers and Turner’s volume consists of an introduction and thirty essays by an impressive list of contributors on some of the most important African American thinkers of the past two centuries. There are essays on folks you thought you knew, but can now know better (Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois), and some who are not often enough recognized as our most brilliant, as they should have been all along (Ida B. Wells, Toni Morrison, Angela Davis). I wish this volume had been available when I was an undergraduate student.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.