Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema meets with IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva. (Photo: @KGeorgieva/Twitter)

Zambia is heading toward critical negotiations to restructure its mounting debts. The IMF has approved a $1.3 billion bailout plan for the country, which will impose cruel austerity measures on the Zambian people.

This article was originally published in Peoples Dispatch.

On September 6, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) unveiled a series of conditions attached to a $1.3 billion loan program for Zambia under an Extended Credit Facility (ECF). The 38-month bailout was announced on August 31 following talks between Zambia and its official creditors to restructure its external debts, which had soared to $17.3 billion by the end of 2021.

As Lusaka heads into these debt relief negotiations, the IMF is imposing brutal austerity measures on the people of Zambia, at least 60% of whom are already living in poverty.

“Zambia is dealing with the legacy of years of economic mismanagement, with an especially inefficient public investment drive,” read a statement by the IMF. Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva went on to add: “Zambia continues to face profound challenges reflected in high poverty levels and low growth. The ECF-supported programme aims to restore macroeconomic stability and foster higher, more resilient, and more inclusive growth.

How exactly does the IMF intend on achieving these goals? Through a “large, front-loaded, and sustained fiscal consolidation” that will reform “regressive and wasteful subsidies” and reduce “excessive and poorly targeted public investment:”

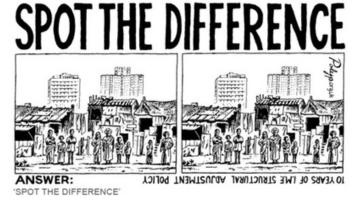

“These are typical, vintage IMF conditions of austerity, which effectively means slowing down government expenditure in quite a drastic way, the brunt of which falls on the poor, on women, and the youth,” stated Dr. Grieve Chelwa, the director of research at the Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy at The New School in New York, USA, in an interview with Peoples Dispatch.

The blow caused by the IMF’s conditions will be swift, with the complete removal of fuel subsidies set to take place by the end of September. Implicit subsidies, including reduced excise on petrol and diesel and zero-rating them for Value Added Tax (VAT), which the government had introduced in 2021 to cushion against soaring inflation and the impact of the pandemic, will also be eliminated. Import duties will be reintroduced.

The Bank of Zambia has already stated that the move will cause a “nudge” in inflation.

Subsidy removal will lead to a rise in electricity tariffs, which will have a demonstrably greater impact on poor households. According to data from the World Bank, only 44.5% of Zambia’s population had access to electricity in 2020. The figure for rural areas was 14%.

The IMF has also taken aim at Zambia’s agricultural subsidies, especially the 20-year-old Farmer Input Support Programme (FISP), and intends to reduce the cost of subsidies to around 1% of the GDP by 2025. The new program will be implemented in the 2023-24 agricultural cycle. According to Chelwa, a million Zambians—or approximately 5% of the country’s population—rely on the subsidy program for maize. A majority of these people, who are responsible for growing the bulk of the country’s maize, are small-scale farmers.

To increase revenues, the IMF has directed the Zambian government to expand its VAT base. This includes a rollback on VAT exemptions on unprocessed foodstuffs, limiting them to “specific items that figure prominently in the food baskets of the poor.”

Between July and September, over 1.35 million Zambians were estimated to be experiencing severe food insecurity driven by high food prices and climate shocks. Out of the 91 districts analyzed, over 15% were facing crisis (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Phase 3) levels of food insecurity. An additional 34 districts are projected to fall under these conditions between October 2022 and 2023.

In an attempt to somehow gloss over the gravity of these measures, the IMF pointed to a projected increase in social protection spending from 0.7% of the GDP in 2020 to 1.6% in 2025, as well as the government’s plans to hire additional staff in the health and education sectors. It also made references to several social safety programmes, including World Bank-supported social cash transfers (SCT), adding that the monthly benefit under the program had been increased from 90 to 110 kwacha ($5.75 to 7) in 2021.

“Overall, for low-income households, the benefits from increased social spending should outweigh the impact from the removal of fuel and electricity subsidies,” the IMF claimed.

“In dollar terms, the increase in monthly benefits is nothing, it is a pittance especially given the increases in fuel prices, electricity prices, and the VAT, which will take place as a result of the Fund’s conditions,” said Chelwa.

Importantly, he added, “social cash transfers are given to the ultra-poor. You have all these distinctions of people characterized as being moderately poor, working poor, ultra poor. However, these are effectively abstract and arbitrary distinctions in countries that are [on the whole] massively poor.”

Not only are taxes on labor income expected to rise in the medium term, Chelwa argued, the rate of this increase will be faster than the taxes on profits in both mining and non-mining sectors, large portions of which are under the control of private corporations, owing to the aggressive structural adjustment and privatization pushed by the IMF and the World Bank in the 1990s.

“These are essentially properties of global and Western capital, so they are going to be treated quite favorably when it comes to taxation. The extent of this favorable treatment in the IMF document is shocking. 70% of the burden of raising new taxes is going to be the VAT; 15% is going to be the corporate sector,” Chelwa said.

“You would think that the IMF would tell Zambia that it was time to tax the mining sector appropriately, but that is conspicuously absent from the document, and this is by design.”

Mining corporations have been given major concessions in recent years, and these have been balanced by drastic cuts to social spending. Meanwhile, by 2019, Zambia’s debt rose to 85% of its GDP. Conditions worsened dramatically with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and debt rose to 118% of the GDP.

In November 2020, even though it was able to secure a debt relief agreement with China, Zambia became the first African country to default on its external debt payments, after it was denied a request for a six month extension on the payment of $42.5 million in interest on eurobonds due in October. However, the crisis had been years in the making.

Debt accumulation in Zambia

After having had most of its debt waived under the IMF and World Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, Zambia began accumulating new debt in 2012.

“Like many poorer countries, Zambia began borrowing from international capital markets based on the advice of international financial institutions,” explained Chelwa. “We were told that the prospects looked good and that the forecasts for commodity prices were strong. It is important to keep in mind that most countries in the Global South are exporters of raw commodities. They told us to borrow, and we went out and took out bonds.”

However, Chelwa pointed to important problems inherent to these bond contracts: “We were borrowing to finance infrastructure projects and expecting to repay in a very short period of time. Returns on projects like bridges, highways, and hospitals can sometimes take decades, but we were expecting to pay back within a decade.”

Compounding the issue was the fact that the “commodity prices, upon which the forecasts were based, crashed and then we have COVID-19 and the climate crisis. Ten years later, the debt is unsustainable, and the way that the international financial architecture is set up, we have to pay no matter what.”

One route is that of the IMF, Chelwa explained further, “where you accept a programme hoping that it will get you into the good books of those you owe money to. However, in actuality this process is quite convoluted and it is not a foregone conclusion that having an IMF arrangement will ensure that creditors treat us better.”

After its initial default in 2020, the Zambian government, under former President Edgar Lungu, formally requested to restructure its debt under the G20 Common Framework in February 2021.

In December, Zambia, now led by incumbent President Hakainde Hichilema, secured a staff-level agreement with the IMF for a bailout of upto $1.4 billion. However, final approval by the IMF board was contingent on assurances that Zambia’s debt could be brought down to levels considered sustainable.

In June 2022, a creditor committee led by China and France was established to deliberate Zambia’s debt relief request under the Common Framework. In July, the creditors agreed to restructure the country’s debts, paving the way for the IMF bailout.

In its report on September 6, the IMF stated that Zambia was seeking debt relief of $8.4 billion between 2022 and 2025. According to Debt Justice, $8.4 billion accounts for 90% of payments to government and private lenders in this period. The organization has called for a permanent cancellation of debt payments, so that these are “not rolled over to the 2030s to fuel another debt crisis next decade.”

With restructuring talks set to begin, one major hurdle stands in the way—private lenders, chief among them BlackRock. The asset management giant is currently the largest owner of Zambia’s bonds, holding $220 million.

On September 16, over 100 leading economists and other experts from across the world wrote an open letter to BlackRock, the G20, and Zambia’s other creditors to engage in a “large-scale debt restructuring, including significant haircuts, in order to make Zambia’s debt sustainable.”

“Over the last decade of low global interest rates, private lenders charged high-interest loans to lower income countries. The supposed logic for charging poorer countries far higher interest rates than richer countries was the greater risk of economic shocks that could make debt repayment more difficult. That risk has now materialized,” the letter noted.

The rise of private lending and crisis profiteering

How is it that private lenders such as BlackRock rose to such prominence when it comes to the debt scenarios in poor countries?

The answer, as Chelwa explained, lies in a major change in the international financial architecture in the past decade or so. “Historically, most indebted countries have borrowed from other countries. It is bilateral debt, and it is coordinated under the framework of the Paris Club, which is essentially this list of wealthy creditor countries,” he stated.

“About 12-13 years ago, the situation changed because countries started getting what are called sovereign credit ratings, from agencies including Moody’s, Fitch, and Standard and Poor’s, after which they could borrow from private lenders. So these countries began to issue bonds. This was the structural change and now we are dealing with the first major crisis of this new architecture,” Chelwa added.

Between 2022 and 2028, 45% of Zambia’s external debt payments are to Western private lenders, 37% to public and private lenders in China, 10% to multilateral institutions, and 8% to other governments.

In 2020, BlackRock was among private lenders which refused to suspend Zambia’s debt payments. While the G20 declared that some bilateral debts would be waived under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), private lenders and multilateral lenders were excluded from the measure. Not only that, private lenders were able to exploit the suspension of debt by official sources to extract full debt repayments.

Between 2021 and 2024, 59% of Zambia’s external debt payments were estimated to be to private creditors. According to Debt Justice, some private lenders stood to make profits between 75-250% from Zambia’s debt if paid in full. This is at a time when people are losing their lives and livelihoods under a deadly pandemic.

In April, Debt Justice estimated that BlackRock could make $180 million in profit for itself and its clients from its investment in Zambian bonds, if the debts were paid in full. This would represent a profit of 110%. Meanwhile, Zambia has cut its health and social protection spending by 20% in the past two years. A report by Oxfam released in May found that the government’s planned cuts between 2022-2026 would amount to more than five times the annual health budget.

The G20 Common Framework provides for coordinated debt relief, and mandates private creditors to participate on comparable terms. Since the start of 2021, three countries—Zambia, Chad, and Ethiopia—have applied for relief under the framework. No help has been given until now.

“The prominence of private lenders is what is going to complicate any attempt to resolve debt,” Chelwa stated. This is because bilateral debt has other, even political considerations. “It is more than financial returns. China has a willingness to suspend interest payments, to restructure debt, to defer it. But are the likes of BlackRock interested in that? What good does suspending debt payment do them?”

“Zambia is a test case, it is also an example of what is to come for much of the Global South as we deal, yet again, with another sovereign debt crisis.”

As entities such as BlackRock continue to reap obscene profits, the people of Zambia will bear the burden of an IMF bailout in which they had no say. In its statements, the Fund increasingly uses the term “homegrown” to refer to the arrangement’s policies. Chelwa has also denounced the co-optation of civil society organizations who lent credibility to the “opaque process that gave birth to such an anti-poor deal.”

“This is the IMF of the 21st century,” he said. “They have learned from their mistakes, not of policy, but of public relations… They call the programme homegrown, yet they impose structural benchmarks. If it was truly homegrown, why would we need an external party to impose milestones?”

Tanupriya Singh is a writer for Peoples Dispatch.