A school handbook paints a picture of youth criminality that is steeped in law enforcement lingo and appears to have been written by police rather than educators.

“You are essentially priming teachers who are otherwise supposed to be interacting with their students and teaching them to now have to identify alleged gang or crew activity.”

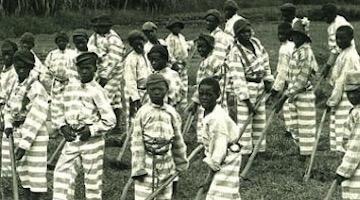

An obscure unit of the New York City Department of Education tasked with addressing “gang and youth violence” in the city’s public schools has been promoting a set of guidelines that reveal serious ignorance of adolescent behavior and perpetuate false and racist stereotypes.

The guidelines, which youth advocates warn put students’ rights and potentially lives at risk, were compiled in a handbook by the Gang Prevention & Intervention Unit, a division of the DOE’s Office of Safety and Youth Development, which relies heavily on schools’ formal relationship with the New York City Police Department. The 14-page handbook is an alarmist compilation of dubious and often absurd claims, listing “personality changes” and “alcohol/drug use” as warning signs of gang involvement and cautions that “females” joining gangs are at higher risk of pregnancy and sexual diseases. The handbook also repeats sensationalistic folklore about gangs, like the idea that initiations require the murder of “an innocent victim, rival gang member, or even a police officer.”

The “GPIU Gang Awareness Information” handbook is part of a set of documents that were obtained through a public records request by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and shared exclusively with The Intercept. It’s not clear how long the guidelines have been in place or how widely they have been used within the city’s schools. Little is known about the GPIU, a unit that dates back to the 1990s but remains largely unknown to the public. While the GPIU technically operates under the DOE, the documents appear to have been compiled at least in part by police officers and repeatedly encourage educators to reach out to law enforcement, raising questions about the collaboration between schools and police at a time when the city has ramped up the targeting of gangs.

“The handbook also repeats sensationalistic folklore about gangs, like the idea that initiations require the murder of ‘an innocent victim, rival gang member, or even a police officer.’”

As The Intercept has reported, in recent years the NYPD has massively expanded a secretive “gang database” that lists tens of thousands of New Yorkers, mostly black and Latino men, even as gang-related incidents make up a fraction of crime in the city. Police can add individuals to the database based on a set of broad and arbitrary criteria that include the people they associate with and locations they frequent — criteria that critics say effectively punish entire communities. You don’t even have to commit any crimes to be added to the database, and there is no clear way for people to learn whether they are listed on it or why.

Most individuals in the database are young — and a recent report by the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College noted that as many as 30 percent were children when they were added to the database. That has raised questions about the role of 5,500 “school safety officers” employed by the NYPD and stationed inside schools, who can also designate students as gang members. While the extent of the cooperation between school-based officers and the GPIU is not clear, the latter also relies on a series of “identifiers” of gang association, including clothing, colors, language, and hand signs, and encourages educators to watch for clues of gang affiliation on students’ backpacks, hats, and notebooks.

The police department, under the leadership of new commissioner Dermot Shea, is also finding new ways to target young New Yorkers. Last month Shea announced a “new youth strategy” aimed at identifying “opportunities for intervention with young people early in the progression that risks turning them into criminals.” The initiative designates 300 police officers as Youth Coordination Officers and taps into the existing School Safety Division to “enhance information sharing” with police outside schools. Hailing the initiative, Mayor Bill de Blasio said last week that it would “[stop] crime before it even happens.” But youth advocates fear that effectively placing children and teenagers under police surveillance both inside and outside school will only funnel more of them into the gang database and the criminal justice system more broadly. And they warn that if guidelines like those outlined by the GPIU are any indication, police are fundamentally ill-equipped to deal with youth-related issues or to train educators on gang interventions.

“There is no clear way for people to learn whether they are listed on the data base, or why.”

“The documents show how the DOE is using gang identifiers and indicators that have the same very subjective and arbitrary criteria that the NYPD relies on,” John Cusick, a litigation fellow at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, told The Intercept. “It’s the same type of surveillance apparatus.”

“These criteria fit into a long pattern of criminalizing students of color,” he added. “You are essentially priming teachers who are otherwise supposed to be interacting with their students and teaching them to now have to identify alleged gang or crew activity.”

A spokesperson for the DOE wrote in a statement to The Intercept that the Gang Prevention and Intervention Unit is a “resource for schools to provide awareness training to schools that identify potential influences and risk factors, or support a student who has been a victim of gang violence.”

“Our schools are safe havens and our student safety work is grounded in the belief that students must be supported through academic and social interventions,” the spokesperson wrote.

A spokesperson for the NYPD did not answer questions about how police work with schools in identifying alleged gang members, instead referring to a recent press conference highlighting the new initiative.

The Department of Education’s Gang Prevention & Intervention Unit lists a series of “identifiers” of gang association, including clothing, colors, language, and hand signs.

A Mashup of Myths

The Gang Prevention and Intervention Unit has operated in the city’s schools since 1994. At one point, the unit was run directly by the NYPD, which under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani took over security operations in the city’s public schools in 1998 — a widely criticized arrangement that remains in place to this day despite a recent effort to limit police’s role in schools. According to the little information about the GPIU available on the DOE’s website, the unit aims to take a “proactive approach to gang activity.” Other material distributed by the DOE notes that the unit assists “schools and community organizations in recognizing the early warning signs of gang involvement.” The work of the unit consists primarily of professional development trainings, gang and bullying prevention programs, and initiatives in collaboration with “local, state, and federal agencies,” the GPIU guidelines suggest. According to the DOE, the unit has two staff members and the handbook “has not been used under this administration.” The DOE spokesperson said that the unit was meant to be “preventative” and that schools reach out to the GPIU “to help better understand how to support students.” Norbert Davidson, a former school safety officer in charge of the unit, told WNYC in 2011 that he visited dozens of schools each month and had trained hundreds of school administrators. Davidson did not respond to a request for comment.

In addition to the guidelines, the set of documents reviewed by The Intercept also includes two lists that name several dozen “crews” — many of which merely indicate street addresses or public housing developments. One of those documents notes that the “GPIU is not responsible for this list of crews which has been compiled by other law enforcement agencies,” even though, as a unit within the education department, the GPIU itself is not supposed to be a law enforcement agency.

In fact, from its definition of a gang to a list of recommended strategies to fight them, the handbook paints a picture of youth criminality that is steeped in law enforcement lingo and appears to have been written by police rather than educators. That raises questions about the sometimes muddled relationship between police and schools. During a 2018 City Council hearing about the gang database, Shea, who before being appointed commissioner led the NYPD’s anti-gang efforts, testified that teachers can serve as sources for the identification of gang members. And the DOE itself has been tracking gang-related disciplinary infractions: a spreadsheet obtained by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund shows that the DOE lists both “gang related behavior” and “violence — gang related” as categories for disciplinary incidents. It’s not clear what criteria the department uses to make those determinations. The DOE did not answer questions about its protocol for accusing someone of gang involvement. The department’s spokesperson wrote that “the DOE does not track or share a database of information regarding students involved in alleged gang-related behavior.”

“The commissioner testified that teachers can serve as sources for the identification of gang members.”

“The question that needs to be posed is, either schools are conducting these assessments based on these broad and subjective criteria, and if not, who else is involved? Who is conducting all this? There’s not a lot of transparency,” said Cusick. “You would assume that these criteria and other factors would be publicly available, especially when you’re subjecting students to certain disciplinary infractions that are specifically tagged as gang-related.”

The GPIU guidelines are filled with platitudes and sensationalism. The document at times reads as if it were written in a different era, revealing a fixation with “vandalism” and “graffiti” that is reminiscent of the Ed Koch administration. It also sounds like it was written by someone who never interacted with a teenager, warning parents and educators to look out for changes in friends, vocabulary, and dress, as well as use of alcohol, drugs, and social media, while at the same time advising that gang “initiation” may include drive-by shootings, rape, and murder. In a section about “female gangs,” the document cautions that “most female gangs are either African-American or Latina” and proceeds to list a series of “Do’s and Don’ts for working with female gangs” that are almost comically sexist.

“This GPIU document on gang culture is just a mashup of myths,” said Babe Howell, a professor at CUNY School of Law who specializes in gang policing and prosecutions. “A lot of what it says are warning signs of gangs is typical adolescence: staying away from home, personality changes, isolation, alcohol. It’s ridiculous.”

“This is a problem because it encourages educators to look at typical signs of adolescent experimentation and see not just potential criminality but gang criminality,” she added. “So instead of being concerned about a kid being badly behaved, now we’re thinking of him or her as a gang member.”

Throughout the document, the authors call on educators to share information with police. They invite them to “read, record, report, remove” graffiti, and to work with “members of the Building Response Team.” The document also refers to a “gang assessment survey” used by schools and to an “intelligence update” training for staff and students. The DOE did not respond to a request for clarification.

“It’s very worrisome how much everything gets back to collaborating with local law enforcement,” said Howell. “It’s bringing law enforcement into this space and saying, ‘If you perceive kids doing what most kids do, changing their clothes, or having cliques — that’s something to call the police about, that’s a law enforcement problem.’”

A Law Enforcement Response

The GPIU gang guidelines are particularly problematic because the unit operates under an agency — the Department of Education — whose understanding of youth-related issues should be far more sophisticated and measured than the document implies. But the unit is just one of several ways in which the public school system has embraced a law enforcement mentality or directly delegated to law enforcement the handling of school-based problems.

After advocates spent years denouncing the role of New York’s schools in the criminalization of youth, the city recently introduced reforms to suspensions and invested in social workers and restorative justice practices. Overall, the number of arrests, restraints, and police interventions in schools has been declining, though not equally across the city.

But youth advocates fear that the progress may be short-lived. The budget for school-based police has steadily increased over the years. In 2018, the city piloted a program to have what it called school coordination agents “wander the halls” in some Bronx schools. And the youth initiative recently announced by the NYPD effectively adds more youth-focused police outside schools to do what school safety officers already do inside. The initiative, which is modeled after an existing neighborhood policing program, invites community organizations to partner with police much like teachers and school staff are asked to partner with school safety officers.

“They are trying to further entrench the NYPD in our schools,” said Kate McDonough, director of the New York chapter of the Dignity in Schools Campaign, which aims to end the so-called school to prison pipeline. “You can’t have restorative justice while also having police in schools, and you can’t truly be restorative if you’re still committing to criminalizing practices like making people go through metal detectors.”

City officials have pitched the new initiative as one that will “protect and serve all kids.” In a press release announcing the program, the police department wrote that “by fostering meaningful connections with teenagers” police would prevent “young New Yorkers from being led on a downward trajectory of crime.”

“They are trying to further entrench the NYPD in our schools.”

At his State of the City address last week, Mayor de Blasio congratulated police on the initiative. “Our young people do not need to be policed, they need to be reached,” he said. “This is about getting to that young person before they ever might commit a crime.”

De Blasio, who has long sought to take credit for a decline in discriminatory police stops that coincided with his election (although those stops are once again on the rise), praised the new NYPD initiative as “the polar opposite” of stop and frisk. “For years in the time of stop and frisk, our young people were treated like they were the problem,” the mayor said. Instead, through the new initiative, police would work on “healing, communicating, inspiring our young people to never even think of a life of crime.”

How they would do that was not immediately clear. A police spokesperson told The Intercept that more details about the initiative would be released when it starts in the spring. And de Blasio himself acknowledged an inherent contradiction in the program when he noted that the 300 youth coordination officers “have that uniform on, they have that badge, they have that gun, that’s true.” The only apparent difference, he seemed to imply, would be their approach. “What are they thinking about every day?” the mayor said. “They’re thinking about how to reach young people who might be teetering on that edge.”

Youth and civil rights advocates criticized the new initiative, arguing that it is not the police’s job to “connect with teenagers.” The announcement also stoked fears that police would use these connections to coax information from the youth they interact with and add more people to the gang database — as one of the current criteria for inclusion is that someone is identified as a gang member by “two independent sources.”

“From a youth advocacy perspective, we don’t want kids talking to law enforcement without their guardian or legal representation. Children don’t always know that sharing something with law enforcement, even in a casual conversation, can expose them to scrutiny,” said Katrina Feldkamp, an attorney with the Education Rights Project at Bronx Legal Services. “The whole point of the new youth coordination officer program is to create more of these casual conversations and increase law enforcement’s surveillance of young people.”

“It is not the police’s job to connect with teenagers.”

Feldkamp, who represents students facing suspension, including some whom schools have accused of gang affiliation, warned that the new initiative would lead to the “type of surveillance and speculation that leads to students being placed in the NYPD gang database.”

“It also creates more pathways for a law enforcement response to incidents that can and should be dealt with at school and in a non-punitive manner that doesn’t criminalize students,” she added.

To students in heavily policed neighborhoods, the new initiative sounds like old news.

Dekaila Wilson, a 19-year-old recent high school graduate and organizer with the school equity group IntegrateNYC, said school safety agents and police were a staple of her high school experience from school hallways to the park, shops, and train station where she went after class. “When you leave school, you see two school safety cars right by the school, then you walk down to the park, and there are two or three of those big vans, and even more cop cars,” Wilson told me. “Students are so used to being criminalized that it’s normal for them.”

Wilson said that in 2017 her Bronx school expelled more than a dozen students who were accused of being in gangs — which she believes administrators determined based on “who was hanging out near the school,” she said. “They lumped them all together and just kicked them all out,” she added. “Some of the students that they kicked out were criminalized so much on a daily basis that they wouldn’t even come to school anymore.”

Andrea Colon, an organizer with the Rockaway Youth Task Force who also recently graduated from high school, said that for young people who already feel targeted by police in their neighborhoods, the realization that they could be labeled “gang members” in school “goes to a different level.”

“School is a place to learn and a place where you should feel safe,” said Colon. “But when you go into schools, not only are you seeing police officers, you also know that you engaging in normal youth behavior can put you on a database that there’s no official process to be taken out of, and there is no way for you to find out that you’re even on it, and a database that is overall racist and shouldn’t even exist in the first place.”

Alice Speri writes about justice, immigration, and civil rights. She has reported from Palestine, Haiti, El Salvador, Colombia, and across the United States. She is originally from Italy and lives in the Bronx.

This article previously appeared in The Intercept.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com