After commandeering a chest x-ray unit in New York City, the Young Lords named it after 19th-century Afro-Puerto Rican physician and abolitionist Ramón Emeterio Betances. (Image Credit: Hiram Maristany. X-Ray Truck II. 1970.)

The late Mutulu Shakur and other Black radicals were responsible for improving the lives of millions of people in the U.S. The counter revolution ended that period of progress, but the political crisis they created forced systemic change on a grand scale.

Inspired by the Cuban Revolution and the Black Panthers, a clique of poor and working class Puerto Ricans founded the liberation organization, the Young Lords, in Chicago in 1968 and opened its New York chapter a year later. The activists got down to business immediately, creating a free, daily breakfast program for children and testing them for lead poisoning, organizing clothing banks and street patrols to monitor police abuse, and launching inmates’ rights and school reform efforts.

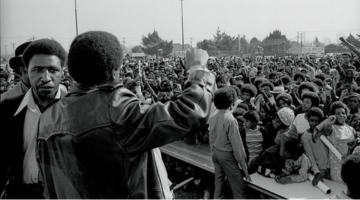

In October of 1969, the militants protested abysmal living conditions in East Harlem and the South Bronx by forming a human chain to block traffic at 125th Street and 2nd Avenue, and lining up rows of garbage cans at the entrance to the Triborough Bridge.

After the hour-long bridge blockage, here is what happened next, according to the historian Johanna Fernandez in her book, The Young Lords: A Radical History:

[t]he Young Lords spontaneously redirected the protesters along 125th Street, Harlem’s major thoroughfare, to the neighborhood’s welfare grievance office on Seventh Avenue, half a mile west of the bridge entrance. According to Young Lord Pablo Guzmán, rerouting a predominantly Puerto Rican march through Harlem offered an opportunity to counteract the “divide and conquer game in the colony”—in which Puerto Ricans and black Americans were pitted against each other on the basis of ethnic differences—and build class unity among them. As he put it, ‘Everybody’s on welfare and everybody’s poor, and everybody should be fighting on the same side of the revolution.’

Fifty-three years ago this week, in the wee hours of the morning on July, 14, 1970, a cadre of Young Lords occupied the main administrative building of Lincoln Hospital, an underfunded, public hospital in the South Bronx that provided health care so derelict that it was known as the “Butcher Shop,” according to Carlos “Carlito” Rovira, an artist who joined the Young Lords at the age of 14.

The 12-hour-standoff ended ambiguously but when a Puerto Rican woman, Carmen Rodriguez, died from an abortion five days after the militants’ takeover of Lincoln Hospital, the combination of events forced the city’s hand; within seven years, construction was completed on a new hospital.

In addition to the new facility, the demand for community control over the hospital produced a revolutionary drug rehabilitation program that eschewed methadone for acupuncture which proved more effective. The acupuncture protocol was the first of its kind in the nation, and was introduced by a Black radical named Mutulu Shakur, who at one meeting of the Young Lords read aloud from a newspaper article that explored a Bangkok doctor’s use of acupuncture to treat a patient’s opium addiction. The article quoted the patient saying that he no longer craved opium after undergoing the acupuncture treatment.

By 1974, hospital administrators acquiesced to the community’s demands and introduced acupuncture as a critical component of Lincoln’s Detox therapy; Shakur would go on to become the program’s assistant director.

“Dr. Mutulu was meeting with our people on a consistent basis,” Rovira said.

Deepening budget cuts would eventually phase out acupuncture therapy but along with his mentorship of his stepson, Tupac Shakur, Lincoln Detox is part of the huge legacy of Mutulu Shakur, who died last week of bone marrow cancer, eight months after he was paroled; he had served 37 years for his role in an armored car robbery that left one security guard and two police officers dead.

Shakur’s generation of radical Black activists represents the sun around which the modern American state orbits, or to say it more plainly, the late 20th century’s most democratizing social movements were in collusion with Black militancy.

“You couldn’t be living during that period of time and not be impacted by the Black Panther Party,” said one Young Lord in the documentary film “Takeover.”

Conversely, the oligarch’s counterrevolution that began in the mid-1970s is, at base, a response to the radical Black polity that Mutulu Shakur represented.

Hence, the political and economic cataclysm that is bearing down on the U.S. results from its rejection of an African-influenced value system that centers pluralism and ordinary people’s rights to govern their own communities.

It may seem hard to imagine today as the country approaches its 250th birthday but 50 years ago, militant Black actors like Shakur were leading America’s workers into battle against the bosses and if we weren’t winning the class war, we were certainly headed in that direction.

For starters, paychecks were fatter than ever. Employees in 1973 earned a larger share of national income –about 51 percent of GDP –than at practically any time in recorded history. Conversely, the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans’ that same year took home their smallest share of national income, roughly 4 percent, than ever before, or since. Couples married, saved, and spent less of their income on housing, a kilowatt of electricity, or college tuition.

Secondly, between 1970 and 1974, the number of African Americans enrolled in college increased by 56 percent, and 15 percent for white students. Just months after the Young Lords’ occupation of Lincoln Hospital, the City University of New York’s vast network of post-secondary schools opened its doors to all of New York City’s high school graduates, responding to demands by Black and Puerto Rican students at City College that university admissions reflect the racial makeup of the city’s high schools, which was at the time, half non-white.

Between 1969 and 1972, the percentage of minority students in the freshman class tripled, but in absolute numbers, it was Italian-Americans who benefited most from the open enrollment policy, doubling from 4,989 in 1969 to 9,803 in 1971.

In January of 1970, St. Louis Cardinals’ center fielder Curt Flood sued Major League Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn for violating federal antitrust laws. At issue was the league’s reserve clause prohibiting players from filing for free agency once their contractual obligation to a team had expired. Flood, who had been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1969, likened the clause to slavery, and attributed his decision to challenge baseball’s owners to the militancy in the streets, telling the players’ union’s executive board:

"I think the change in black consciousness in recent years has made me more sensitive to injustice in every area of my life."

Despite support from retired players including Jackie Robinson and baseball’s first Jewish superstar, Hank Greenberg, Flood lost the lawsuit which was ultimately heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. But the international reserve clause was abolished in 1976. Salaries for all professional athletes skyrocketed.

In August of 1970, tens of thousands of protesters poured into the streets across America for the Women’s Strike for Equality in the largest women’s rights demonstration since the suffragists. The following month, two African American employees at Polaroid in suburban Boston, Caroline Hunter, a chemist, and Ken Williams, a photographer, were on their way to lunch when they noticed a bulletin board mock-up of an identification card. The caption read: “Department of the Mines, Republic of South Africa.” The couple did some digging and discovered the ID cards were used by South Africa’s white minority to enforce the police state known as apartheid. When Hunter and Williams raised their objection to Polaroid executives, they were initially ignored, and ultimately fired, yet the couple went on to birth the international divestment movement that led to South Africa’s first all-races election in 1994.

Even the arch-villain Richard Nixon got in on the act, creating the Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, and introducing plans to provide a guaranteed minimum income to all Americans. Lawmakers did not pass the legislation but it was the basis of the Earned Income Tax Credit which continues to this day to supplement the paychecks of millions of low-wage employees. Two years later, Congress approved the Section 8 rental subsidy program which provides roughly five million low-income families with housing vouchers. Meanwhile, voters in 1973 elected eight black, big-city mayors including Tom Bradley in Los Angeles, Maynard Jackson in Atlanta, and Coleman Young in Detroit. Before the decade was over, at least six other cities would elect black mayors, including Ernest “Dutch” Morial in New Orleans, Richard Arrington in Birmingham, and Marion Barry in the nation’s capital.

Artistic expression flourised. Melvin Van Peebles released the movie Watermelon Man in 1970 followed by Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song the following year. The Spook Who Sat By the Door hit the big screen in 1973, Chinatown and Claudine in 1974, Cooley High the following year. At the 1973 Academy Awards, Marlon Brando sent Native American actress and activist Sacheen Littlefeather to refuse the Oscar he’d won for the Godfather, as a protest against ugly Hollywood stereotypes of Native Americans, and in support of the American Indian Movement. Later, in an interview with Dick Cavett, he credited African Americans for inspiring him to act.

“The blacks have brought about changes because they were just damn angry about it and they thumped the tub and threatened and made some noise about it but if they had just been silent and thought ‘well gradually wisdom will come to those who are in the business of the movies and they will do right by us’ the day would never have come. We have a lot to be grateful for that the blacks were as insistent as they were . . . but it’s a block-by-block fight.”

What was occurring was nothing less than a nationwide mutiny. Nearly 2.5 million employees walked off the job in 381 labor strikes in 1970, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; there were another 298 work stoppages in 1971, 250 in 1972, 317 in 1973 and 424 labor strikes in 1974, the third-highest total ever.

David Rockefeller, a Chase Manhattan Bank board member wrote in 1971: “It’s clear to me that the entire structure of our society is being challenged.”

In 1973, 25-year-old Eddie “Oilcan” Sadlowski launched a grassroots campaign for the directorship of the United Steelworkers District 31, representing mills on Chicago’s South Side and across the state line in Gary, Indiana. Sadlowski’s bid for the union position was a rebuke of the collective bargaining agreement negotiated by the USW leadership, in which the rank-and-file forfeited their right to strike in exchange for regular pay raises. Under the banner, “It’s Time to Fight Back,” the burly and gregarious Sadlowski garnered wide support from his black, Latino, and white coworkers, and had an understanding of the class question that mirrored Fred Hampton’s.

The biggest thing management has had going over the years is this game of divide and conquer –especially between whites and blacks. Like my pa used to tell me about the sharecroppers down South. The black sharecropper would get a house that was just a little bit better than the white guy . . but the white guy would get a dime more on a bale of cotton than the black. And so they’d always be jealous of each other about something and always fighting each other instead of the boss.

Sadlowski’s takeover attempt failed but the proliferation of wildcat strikes indicated that employees were not merely willing to go to war with the bosses but with their own leadership as well. Flouting a law prohibiting federal employees from striking, New York letter carriers on March 17th, 1970 voted 1,555 to 1055 to walk off the job in protest of a 5.4 percent pay raise which was less than the inflation rate and far less than the pay hike of 41 percent that Congressional lawmakers awarded themselves that year. Within days 152,000 postal workers in 671 locations across the country had followed suit, walking off the job in the biggest wildcat strike in U.S. history. Nixon called in 24,000 military personnel to deliver the mail but they weren’t up to the task. Negotiators ultimately agreed to a wage increase of 14 percent.

Defying the UAW, 7,500 employees walked off the job two years later at the General Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio. Executives sited the plant on an 80-acre cornfield about 60 miles southeast of Cleveland to escape the nettlesome Black workers in the big city only to find that their influence stretched far beyond the city limits.

The Empire began to strike back in earnest in 1971. Prior to accepting the Nixon administration’s nomination to the highest court in the land, a courtly, Southern corporate lawyer named Lewis Powell delivered a “Confidential Memorandum” to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Polemically entitled the Attack on the American Free Enterprise System, the seven-page communiqué that became known as the “Powell Memo” made only a single explicit reference to the issue of race, but recommended that big business regain its footing by isolating criticism of its operations to “minority ” communities, thereby short-circuiting its disquieting spread to “perfectly respectable elements of society” such as college campuses, the pulpit, the media, literary journals, the arts and sciences, or, in short, white America. In measured language, Powell proposed nothing less than the corporate takeover of America’s dominant institutions, a reshaping of democratic discourse through "constant surveillance" of textbook, newspaper and television messaging, the aggressive promotion of conservative academic voices and, where possible, a purge from public life of the most radical Leftist elements.

The super-rich began almost immediately putting Powell’s plans into action. One-hundred-and twenty-five of the nation’s largest industrial, commercial, and financial corporations formed the Business Roundtable in 1972 to lobby the federal government for corporate tax cuts, deregulation of the transportation and financial industries, and labor law “reform.” The Roundtable was followed in short order by the founding of the conservative Heritage Foundation in 1973, the libertarian Cato Institute the next year, and a series of ad hoc business-based coalitions that helped defeat legislative efforts to create a Consumer Protection Agency.

The result is an imminent catastrophe that accrues from the FBI’s counterintelligence progam, known as COINTELPRO, and simultaneous efforts to ship manufacturing jobs offshore, short-circuiting the fuse box for radical Black Power activism.

The America of today is the complete opposite of the one taking shape in 1970. There are no unions, few labor stoppages and even fewer protests such as the Young Lords’ garbage protest or the takeover of Lincoln Hospital. And most vitally, there are almost no Black radical voices at City Hall or participating in national political discussions.

Mutulu Shakur’s death represents both the end of a radical Left in America, and an opportunity to resurrect it. After the 1981 robbery of the Brinks’ truck, Shakur evaded arrest for years before the police finally caught up to him on February 12, 1986. In addition to racketeering, conspiracy, armed robbery and murder charges, Shakur was tried, along with the white radical activist Marilyn Buck, with helping engineer Assata Shakur’s escape from a New Jersey prison.

“The Young Lords drew so much energy from Dr. Mutulu and Mumia Abu Jamal and so many other Black activists,” Rovira said. “That is why the government targeted them for destruction.

All of our most successful struggles were led by Black revolutionaries.”

A former foreign correspondent for the Washington Post, John Jeter is the author of Flat Broke in the Free Market: How Globalization Fleeced Working People and the upcoming Class War in America: How the Elites Divided the Nation by Asking Are You a Worker or Are You White?