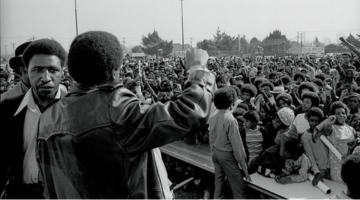

Hill’s bold statement to the UN is part of the internationalist Black radical tradition, exemplified by Paul Robeson, the Black Panther Party, and today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

“Black internationalists believed true liberation necessitated a radical reordering of U.S. politics and international relations.”

Last week, Marc Lamont Hill, academic, activist and media personality, addressed the United Nations at its commemoration of the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People. Hill’s speech was a bold call because it countered U.S.-led orthodoxy clinging to a two-state solution despite a one-state reality in which Palestinians are neither sovereigns of their own state nor citizens of Israel. Hill’s closing words, imploring international actors to support Palestinian freedom “from the river to the sea,” effectively demanded the dismantlement of an apartheid regime and the establishment of a bi-national state. In that sense, his views are commensurate with leading voices critical of the status quo in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet apologists for Israeli policies quickly mobilized a vicious smear and harassment campaign. CNN responded by firing Hill, and the chairman of Temple University’s board of trustees said he was searching for ways to essentially punish Hill, a media studies professor there.

“Hill’s speech echoed a discourse and vibrancy once emblematic of diplomatic revolutionary efforts at the United Nations.”

Understanding the significance of Hill’s address and the motivations of his detractors requires us to move beyond the immediate question of Palestine and issues of academic freedom and free speech. His speech forms an important part of a renewed manifestation of Black-Palestinian solidarity, itself a component of a longer legacy of black internationalism and Third Worldism. In this sense, his speech echoed a discourse and vibrancy once emblematic of diplomatic revolutionary efforts at the United Nations that had receded in the folds of a collapsed internationalism.

The U.N. General Assembly established the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People in 1977 in the wake of systematic U.S. efforts to undermine an international resolution to the question of Palestine. This U.S. intransigence formed part of its imperial global role, ranging from military interventions in Vietnam to its diplomatic protection of apartheid South Africa in the U.N. Security Council. In the context of decolonization and the groundswell of newly admitted states, the General Assembly emerged as the primary expression of the preferences of the international community. An overwhelming majority of these states, constituting the self-described Third World, considered Palestinian liberation as central to its agenda for challenging Western dominance and establishing a new international order. A key example is the passing in 1975 of UNGA Resolution 3379 describing Zionism as a form of racism.

“American black radical thinkers and organizations considered racism and colonialism as co-constitutive systems of domination and articulated an internationalist vision for liberation.”

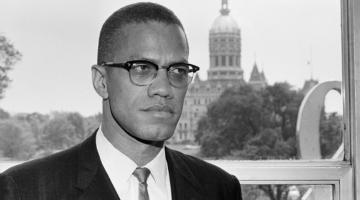

American black radical thinkers and organizations identified with Third World movements and helped shape this global uprising. They considered black communities in the United States as the Third World within the First World. Organizations, including the Black Panther Party and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, as well as individuals such as Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Robert F. Williams and Harold Cruse, considered racism and colonialism as co-constitutive systems of domination and articulated an internationalist vision for liberation. This vision aligned black radicals with revolutions in China and Cuba as well as anti-colonial struggles across the African continent, Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

The U.S. government, together with liberal foundations, universities and media outlets, might have tolerated black calls for integration into the existing U.S. system. But black internationalists believed true liberation necessitated a radical reordering of U.S. politics and international relations. So the U.S. government sought to systematically discipline them with unmitigated force.

In 1956, the House Un-American Activities Committee interrogated Paul Robeson, acclaimed theater and screen actor, all-American football player and activist, for his communist affinities. The committee blacklisted him, the State Department stripped him of his passport for eight years, and professional concert halls refused to book him. Robeson was not deterred. In 1951 and on behalf of the Civil Rights Congress, he submitted an anti-lynching petition to the United Nations charging the United States with genocide of black people. In 1967, the U.S. government blacklisted Muhammad Ali from professional sports, stripped him of his heavyweight boxing title and fined him $10,000 as punishment for his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War . The Supreme Court would not overturn his conviction until 1971. In the late 1960s, the FBI launched the Counterintelligence Program to decimate black radical movements. The program was premised on surveillance, infiltration, politicized trials, forced exile and assassinations.

“Robeson submitted an anti-lynching to the United Nations charging the United States with genocide of black people.”

Within this context, disdain for advocacy on behalf of Palestine was particularly acute and targeted even moderate black leaders. In 1979, the first black U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young, informally met with a Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) representative at the United Nations. The United States had excluded the PLO from the Middle East peace process inaugurated in late 1973. It sought to subvert the establishment of a Palestinian state by first creating bilateral peace treaties between Israel and several Arab states and then to impose a solution upon the Palestinians. Young’s meeting with the PLO representative was a bold attempt to achieve a breakthrough. Israeli representatives responded harshly and called for Young’s immediate removal. The first black U.N. ambassador resigned over the incident. James Baldwin, acclaimed novelist, thinker and activist, said Young was “betrayed by cowards” .

“Black Lives Matter (BLM) member groups published a platform squarely endorsed solidarity with Palestinians.”

This history is alive and well. Contemporary renewals of Black-Palestinian solidarity have faced aggressive attacks by the U.S. liberal establishment. In 2016, Black Lives Matter (BLM) member groups published a platformoutlining domestic and international policy toward the advancement of black freedom. It squarely endorsed solidarity with Palestinians. In the section on U.S. foreign policy, it described Israel’s treatment of Palestinians as tantamount to genocide and endorsed the call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) of Israel. The backlash was severe and included funding cuts for several groups as well as applying pressure to cancel Black Lives Matter events that were unrelated to Palestine. BLM member groups understood the backlash as an attempt to dictate the scope and vision of black freedom. Tolerating none of it, they made no amendments to the platform and reiterated their solidarity.

The concerted attacks on Hill not only represent a liberal heterodoxy and double standard on the question of Palestine. They also fit into a legacy of repressing black internationalists and the black radical tradition in the United States. Ironically, this episode is making vividly clear what a transnational movement has proclaimed for decades: Black and Palestinian struggles are entwined and represent a joint struggle for freedom. In its attempt to squash this trend, the liberal establishment, led by CNN, has inadvertently made this movement even stronger.

Noura Erakat is a Palestinian American human rights attorney and assistant professor at George Mason University. She is the author of “Justice for Some: Law as Politics in the Question of Palestine,” which will be published next year by Stanford University Press.