The killing of Timothy Thomas in 2001 ignited Cincinnati’s long-simmering tensions over police violence. This struggle continues today, forcing a painful question: When justice is denied, does violence become the only language of resistance?

Wanting cigarettes, 19-year-old Timothy Thomas left the Cincinnati apartment he shared with his girlfriend and infant son around midnight on April 7, 2001. Later that night, two off-duty police officers spotted him emerging from a nightclub called The Warehouse and called dispatch to announce:

“Ah, we have a suspect, male, Black about 6 feet, red bandanna, last seen eastbound on 13th. He has, ah, about 14 warrants on him.”

The warrants were all for nonviolent offenses, mostly traffic charges. Nonetheless, Thomas spotted the patrolmen spotting him, and a foot chase ensued through Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood that was settled by 19th-century German immigrants but was home to a mostly poor, African American population by 2001.

Around 2:00 in the morning, a white police officer–who would later acknowledge that the unarmed teenager startled him– fatally shot Thomas once in the chest.

Three days later, the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood was on fire.

Thomas’ death brought to 15 the number of African American men killed by Cincinnati police officers between 1995 and 2001. In the most high-profile of these cases, police mistook Roger Owensby Jr.--a sergeant in the U.S. Army who had no criminal record—for a drug dealer, put him in a chokehold, maced, and beat him. Officers were tried and acquitted.

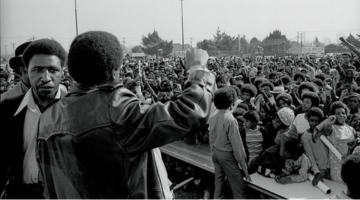

Thomas’ killing was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back, Shouting “no justice, no peace” and “stop the violence” hundreds of protesters assembled outside the Over-the-Rhine police precinct on April 9, hurling cans and rocks at police officers wearing riot gear, and shoving their way into the police precinct. Cincinnati police officers pelted the crowd with bean bags, rubber bullets, and tear gas, but that did little to deter the rebellion, which mushroomed the following day; hundreds of insurrectionists hurled trash cans at not just police but through the windows of local businesses, setting fire to a farmers’ market, and looting and vandalizing stores. Scotty Johnson, president of a fraternal organization of African American police officers known as the Sentinels said at the time:

“I think what happened here…was a long time coming. The city council and administration had forewarning for years about the bad climate between Cincinnati police officers and the Black community, but nobody paid attention. Now I think the message has been sent that we need to quit playing games with police officers-community relations and do some concrete things to bring our city back together.”

And that is exactly what happened. The violence began to dissipate when Cincinnati Mayor Charlie Luken declared a state of emergency, and ordered a four-day curfew. But he emerged from the ordeal singing a different tune: whereas he and other city councilors had mostly ignored African American grievances about police violence, he now acknowledged and pledged to do something about it.

“There’s a great deal of frustration within the community, which is understandable. We’ve had way too many deaths in our community at the hands of Cincinnati police officers… I’m not asking anyone not to be frustrated but to just realize in the short-term someone could get hurt.”

At a press conference a week after the insurrection, he told reporters:

"We have been a community in crisis. Now that the disturbances have subsided, they must never occur again. We have an opportunity for a new Cincinnati. This city is committed to eliminating all inappropriate police violence. We will not tolerate injustice in any form. We need immediate improvement and strong city and police leadership accountability for these results."

The changes were immediate. Within days of Mayor Luken’s address, the Justice Department announced that it would review the Cincinnati Police Department’s practices, and in 2002, city officials and the police union entered into a collaborative agreement with the ACLU and an activist organization, the Black United Front. Designed to improve officer training–encouraging the use of tasers rather than firearms for instance– and strengthen the relationship between police and the African American community, the collaborative agreement was unprecedented, paying the RAND Corporation, as one example, $1 million to survey residents. Iris Roley, project manager for Cincinnati’s Black United Front, said in a 2019 interview:

“We had paid RAND millions of dollars to come in here and survey us during this process. I can’t find a Black person that was ever surveyed by RAND. Nor has the city ever paid us a million dollars to do a survey, either.”

The collaborative agreement is widely credited by Roley and others in Cincinnati’s African American community with reducing police violence in their neighborhoods. But it has not altogether eliminated police terror against Blacks as evidenced by the fatal shooting of 18-year-old Ryan Hinton last Thursday. Police say that the African American teenager pointed a gun at police as he fled from a stolen car; his death was the fourth police shooting so far this year in Hamilton County, two of them fatal. Prosecutors have determined that the first three were all justified shootings.

Hours after seeing video footage of his son’s slaying last Friday, police say that his father, 38-year-old Rodney L. Hinton, drove his car into a Hamilton County sheriff’s deputy, Larry Henderson, killing him. Henderson had no connection to the fatal shooting of Hinton’s son but police say that Hinton plowed randomly into the slain police officer to avenge his son’s death.

Hinton was charged with aggravated first-degree murder, a capital offense, but city officials are clearly on edge and apprehensive about the fire next time. Prosecutors have appealed for calm in the Black community, urging African American clergy and others to “let the process work.”

While Hinton’s guilt or innocence has not yet been adjudicated, what is irrefutable is that the horrific act of which he is accused underscores both the permanence of state terror against African Americans and the effectiveness of violence as a tool to combat it. Had the elder Hinton not responded to his son’s killing, it would’ve almost certainly been confined to the local media for a period of a few weeks or a few months at best, similar to the series of police killings of Black men a generation ago if not for the African American community’s violent response.

As it stands, however, the Hinton family’s ordeal is a national story, and across the country, on social media, in barber shops and beauty salons, African Americans are once again debating what role violence should play in fighting our oppressors. While it remains a point of contention, particularly in light of the October 7, 2023 military assault by the Palestinian resistance against Israel’s illegal occupation, international law recognizes the right of subjugated people to use violence as a means of gaining self-determination. Moreover, the consensus among post-colonial scholars is that violence is the surest way to grab the attention of an indifferent oppressor.

Paraphrasing the most famous anti-colonial intellectual, the French psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, one African American posted on social media this weekend:

“Violence is the only language the white man understands.”

Several others recalled a 2014 address by Nation of Islam leader, Louis Farrakhan, in which he spoke of the recent killings of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner, reminding students at Baltimore’s historically black institution, Morgan State University, that both the Koran and the Bible invoked a “law of retaliation,” and “a life for a life.”

“And as long as they kill us and go to Wendy’s and have a burger and go to sleep, they’ll keep killing us. But when we die and they die, then soon we’re going to sit at a table and talk about it! We’re tired! We want some of this earth or we’ll tear this goddamn country up!”

Continuing, Farrakhan scolded parents for telling their children about “compromising,” and preachers for “being the pacifier for the white man’s tyranny.”

Violence, or its threat, has long played a role in African liberation movements worldwide. The anti-lynching activist and muckraking journalist, Ida B. Wells is widely known for her exhortation:

“A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

Similarly, Malcolm X’s denunciation of nonviolence as a revolutionary tactic influenced the Black Panthers and others, as did efforts by Robert Williams and the Deacons of Self-Defense to promote gun ownership in the final stages of the civil rights era. Lesser known is the role that violence played in thwarting white mobs out for blood in Atlanta’s 1906 race riot, as well as the Red Summer of 1919, in which Black World War I veterans helped defend Black communities from attack, or formed militias that discouraged white supremacist incursions from alighting on their communities in the first place.

And while South Africa’s iconic liberation hero, Nelson Mandela, is largely remembered as a kindly old man who led a peaceful transition from apartheid to democracy, he founded the African National Congress’ paramilitary wing, uMkhonto weSizwe–or Spear of the Nation–to attack the white-minority government’s military installations. It was the actions of uMkhonto weSizwe, known as the MK, that led to his arrest and 1961 trial on charges of treason, in which he said defiantly to the court:

“The time comes in the life of any nation when there remain only two choices – submit or fight. That time has now come to South Africa. We shall not submit and we have no choice but to hit back by all means in our power in defense of our people, our future, and our freedom.”

Years later, when Mandela was imprisoned at the notorious penal colony on Robben Island near Capetown, Chris Hani, the head of South Africa’s Communist Party and commander of uMkhonto weSizwe, urged Mandela to expand the scope of military installations to the white civilian population. When Hani was assassinated in 1993, he was the country’s second most popular politician after Mandela.

Today, 30 years after South Africans of all races went to the polls for the first time to abolish apartheid, many Blacks lament that they failed to capitalize on what Fanon dubbed the “dragonslayer effect” in which the colonized gains confidence from the act of killing the colonizer. In fact, it is hardly uncommon to hear Black South Africans say even today:

“We missed an opportunity to push the whites into the sea.”

Perhaps the starkest comparison to be made, however, is between the elder Hinton and the plot of one of Toni Morrison’s most cherished novels, Song of Solomon. Published in 1977, the novel centers on a young African American who is recruited to join a secret society of Black vigilantes known as the Seven Days that was created in response to the lynching of Emmet Till. The Seven Days avenged racist violence on African Americans by attacking random whites in a similar fashion. Each member of the group is assigned a day of the week so that if an African American is assaulted on a Thursday, the vigilante assigned that day would be responsible for avenging their injury or death.

Sandra Adell, a recently retired professor of African American studies at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said that it is difficult to discern Morrison’s inspiration for the Seven Days. On the one hand, she writes sympathetically of the Black men who form the secret society, but on the other hand she implies that the guilt of killing white people at random weighs heavily on each of the members, and hints that it may have driven them insane. Said Adell in an interview with Black Agenda Report:

“This is what Morrison imagined. How it relates to the grief experienced by the father in Ohio is difficult to say. If I were still teaching, I would certainly discuss the Seven Days in relation to his revenge killing.”

Jon Jeter is a former foreign correspondent for the Washington Post. He is the author of Flat Broke in the Free Market: How Globalization Fleeced Working People and the co-author of A Day Late and a Dollar Short: Dark Days and Bright Nights in Obama's Postracial America. His work can be found on Patreon as well as Black Republic Media.