In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Erik S. McDuffie. McDuffie is Associate Professor of African American Studies and History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His book is The Second Battle for Africa: Garveyism, the US Heartland, and Global Black Freedom.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Erik S. McDuffie: The Second Battle for Africa: Garveyism, the US Heartland, and Global Black Freedom (Duke University Press, 2024) does more than just examine the importance of the U.S. Midwest to shaping the twentieth-century Black world through Garveyism. Through research I conducted in Ghana, Grenada, Jamaica, Liberia, South Africa, Trinidad and Tobago, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, my book elucidates how we arrived at this current political moment in which the United States and countries across the world are moving toward fascism. Trump didn’t just appear from nowhere. Instead, my book shows us how we got to where we are today, nationally, and globally.

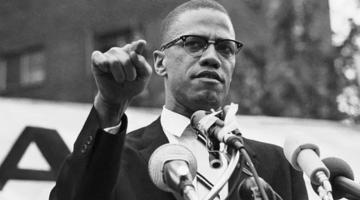

The Midwest constitutes a key site where white supremacy, gendered racial capitalism, and settler colonialism took shape in the United States from its very beginnings. US heartland-based Black nationalists, inspired by Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and its offshoots, in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Omaha, Lansing, St. Louis, and rural areas, were at the forefront in recognizing the centrality of race to the making of the modern world and in fighting for global Black liberation. These Midwest-linked Garvey formations included the Nation of Islam, Moorish Science, Peace Movement of Ethiopia, Afro-American Institute, Revolutionary Action Movement, Movement for Justice in Africa, Marcus Garvey Institute, Marcus Garvey Memorial Institute, Beth Shalom B'nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation, and Malcolm X College. My book brings to light dynamic, Midwest-based Black men, women, and youth, inspired by Garvey--Louise Little, the Grenada-born, grassroots, pan-African organizer best known as the mother of Malcolm X; Mittie Maude Lena Gordon of Chicago, a champion of Liberian colonization; James Stewart of Cleveland, who succeeded Marcus Garvey as the president-general of the UNIA and moved in 1949 with his wife, Goldie Stewart, and family, to Liberia to realize Garvey’s dream of relocating the UNIA’s headquarters to West Africa; and the Rev. Clarence Harding of Chicago who moved to Liberia in 1966 to advance “the second battle for Africa” during the height of the African decolonization through the UNIA and transnational Black radical formations such as the Movement for Justice in Africa based in the Liberian capital of Monrovia. My book, then, provides a long history of Black nationalism in which the Midwest was prominent and how Black people in the heartland were at the frontlines globally in fighting for Black liberation.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

I want activists and community organizers to understand that the struggle for freedom is long and difficult but also incredibly rewarding and transformative. The story of Louise Little is a case in point. Until recently, she has been erased from historical narratives about Malcolm X, Garveyism, and Global Africa. She was brilliant. She suffered so much during her life. But she was resilient. As I often say, no Louise Little, no Malcolm X. She was critical to cultivating his Black radical internationalist sensibility, which propelled him into the global spotlight as an uncompromising Black revolutionary.

In addition, I want activists and community organizers to understand that liberatory movements too often reproduce the very oppressions they seek to eliminate—heteropatriarchy, empire, settler colonialism, and authoritarianism, among other pernicious forces. We can see this in how Garvey and some midwestern Black nationalists, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, James Stewart, and Malcolm X, collaborated with white supremacists in pursuit of Black freedom. My examination of collaborations among Black nationalists and white supremacists is one of the topics in my book that most intrigues people. Indeed, I hope my book highlights the messiness of Black movements. Recognizing and working through these contradictions and paradoxes is how, I think, we move forward.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

First and foremost, I want my readers to “unlearn” the prevailing idea of the U.S. Midwest as a provincial place devoid of Black people. Nothing could be further from the truth. As my book shows, the region we now call the Midwest has been a generative site and at the front lines of struggles for global Black freedom since the late eighteenth century. It never ceases to amaze me when I hear Black people, usually from New York and other east or west coast US cities, express shock that there are Black people in the U.S. heartland or that we’re a bunch of country bumpkins in places like Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis, among other places. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In addition, I want to challenge scholarly and popular assumptions that frame African American midwestern life solely with the confines of the United States and that erase the Midwest from the African Diaspora. Part of what drives this book is my desire to expand the geographic and temporal scope of the African world through centering Garveyism in the U.S. heartland.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

Where to begin? Black scholars and intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois, Karl Marx, Ida B. Wells, Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, CLR James, Frantz Fanon, St. Clair Drake, Walter Rodney, Maurice Bishop, Angela Davis, Cedric Robinson, Faye Harrison, Barbara Smith, Audre Lorde, Eileen Boris, Robin Kelley, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Barbara Ransby, Ula Taylor, and Michael West, among countless other scholars, inspire my work. I am also a huge blues, jazz, Afrobeat, salsa and Afrobeats fan. So, add Louis Armstrong, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, Celia Cruz, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Fania All Stars, Ella Fitzgerald, Flavour, Gran Combo, Billie Holiday, John Lee Hooker, Robert Johnson, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, Seun Kuti, Hector LaVoe, Abbey Lincoln, Tito Puente, Sonny Rollins, Pharoah Sanders, Nina Simone, Bessie Smith, Koko Taylor, Randy Weston, and Muddy Waters to the people who inspire me to write about Black people and Black movements who imagined that another world is possible.

Perhaps the intellectual who most inspires me is Gerald Horne. He’s one of the most important and prolific Black scholars of our time. I deeply respect him. He is unapologetic about his Black radical internationalist politics and his outspoken opposition to U.S. imperialism.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

This is such a hard question. There are so many great books that have come out in the past five years that are brilliant. If I had to choose, then my first choice would be Gerald Horne’s The Counter-Revolution: Texas Slavery & Jim Crow and the Roots of U.S. Fascism (New York: International Publishers, 2022) As discussed, I am huge fan of Gerald Horne. His work is so timely. His (re)framing of the American Revolution as a “counter-revolution” and the United States as a reactionary project predicated upon white supremacy, settler colonialism, and feudalism is so on time for appreciating how we arrived at this fascist historic moment in the United States.

Next, I really dig Michele A. Johnson and Funké Aladejebi edited volume Unsettling the Great White North: Black Canadian History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022). The book is ground-breaking in its rethinking of Black Canadian history and in challenging the myth of Canada as a “multicultural” refuge for anti-Black racism. Even more, the volume is brilliant in how it expands the geographic and temporal analytical scope of the African Diaspora through calling attention to the dynamism and complexities of Black Canadian history and life.

Horne’s The Counter-Revolution: Texas Slavery & Jim Crow and the Roots of U.S. Fascism and Johnson and Aladejebi’s edited volume Unsettling the Great White North will be critical for framing my next book tentatively titled, Rather Die in Australia a Poor Man than to Live in His Country a Poor Man: The Diasporic Life and Journeys of Ohio Black Abolitionist Globetrotter John Hatfield. This book is about my great-great-great grandfather who agitated against slavery in Cincinnati, Ohio, Canada, and Australia prior to the U.S. Civil War. Horne’s emphasis on the U.S. as a reactionary, counter-revolutionary project and Johnson and Aladejebi’s insistence in centering settler colonialism and Indigenous people to our understanding of Black Canadians and their struggles for freedom will be critical to how I understand my ancestor’s activism and diasporic journeys.

Roberto Sirvent is the editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.