This week’s featured author is Nyasha Mboti. Mboti is Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Science at the University of the Free State in South Africa. His book is Apartheid Studies: A Manifesto.

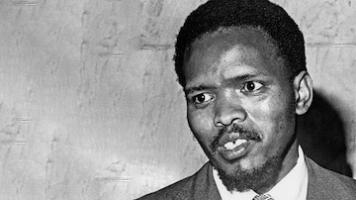

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Nyasha Mboti. Mboti is Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Science at the University of the Free State in South Africa. His book is Apartheid Studies: A Manifesto.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Nyasha Mboti: Apartheid Studies: A Manifesto is a study of how oppression persists – how the oppressed live in harm’s way and what can be done about it. The study of the maintenance and persistence of oppression is, for me, the question of the 21st century. Society has lived far longer under oppression, poverty, injustice, and harm than without them – this despite all the policy work, initiatives, campaigns, and trillions of dollars that have been thrown at these problems ostensibly to end them. Why does life go on if people live in harm’s way? How is this the case? I propose in the Manifesto that the study of the maintenance and persistence of oppression in society is best done through utilizing the (till now) neglected notion of apartheid as a theoretical framework. A little studied, little understood aspect of apartheid in South Africa is how the oppressed lived with harm and lived in harm’s way for so long. A study of the mechanics of oppression shows three things. Firstly, it shows that no two oppressed people in the world experience the same sort of oppression at the same rate – a fact which greatly and critically complicates our attempts to abolish injustice. Secondly, unless we have a new theory and practice of understanding oppression, then injustice and harm will appear to have ended (for instance, with the Emancipation Proclamation, or the culmination of Civil Rights, or declarations of independence in African countries, or Freedom Day on 10 May 1994 in South Africa etc.) but in fact the prevalence and virulence of harm remains intact. Oppression does not go away but merely becomes undetectable. Thirdly, oppressors cause oppression to be undetectable by billing the costs of oppression on the oppressed themselves. Apartheid Studies as a theoretical framework and practice seeks to resolve the 3-part problem of persistent oppression by focusing on prevalence, virulence, undetectability.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

Apartheid Studies is a new field from the global south that utilizes the notion of apartheid to leverage the experiences and aspirations of the oppressed to show how oppression persists and what to do about it. Apartheid Studies: A Manifesto is targeted at researchers, scholars, activists, community organizers, students, policymakers, and general readers who have a cross-disciplinary interest in how oppression, injustice, inequality, poverty, and harm persist, and what can be done about it. From the book, readers will take away a redefinition of apartheid that is more faithful to how the oppressed experience a life of persistent oppression. This redefinition helps us to see that apartheid takes forms that are very different to what we have been told or what we ordinarily assume. In practice, apartheid is present in every society where oppression persists, from Kenya to Canada, Brazil to Bulgaria, the US to Uganda, Israel to India, South Africa to the UK, and so on. The book shows that apartheid is how oppressors bill and invoice the costs of oppression on the oppressed themselves, thus allowing oppression to persist mostly undetectably. Oppressors thus go on holiday, because they no longer need to be physically present to maintain systems of oppression. Instead, the oppressed themselves oversee the maintenance of their own oppression without even meaning to do so. I show how this happens and what we can do to abolish oppression for good.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

I hope that readers will be disabused of the notion i) that oppression is temporary and transitional (in fact, oppression is never meant to end), ii) that injustice, poverty and inequality constitute crises (in fact, these are not crises if the people suffering, dying and being harmed are the same ones who have always been harmed), iii) that “solidarity” amongst the oppressed is possible (in fact, all the oppressed experience oppression at different rates – hence you will always find a few hundred or few thousand black people at, say, a Black Lives Matter march even if most black people are against police brutality), iv) that there is such a thing as class (in fact, you are either oppressed or you are not), v) that there is such a thing as mental colonization (again, either you are oppressed or you are not). We need an overhaul of how we understand oppression. The old constructs seem insufficient. Our spirited attempts to dismantle oppression merely entrench it. Something is just not right, and nothing is working as we quite intend it to. The new field of Apartheid Studies affords us a new understanding of why things are the way they are in the world, and what to do about it. It is not perfect. Far from it. The framework needs to be tested from a variety of positionalities, disciplines, and perspectives. Apartheid Studies: Manifesto is thus an invitation to interdisciplinary work in dismantling oppression.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

The intellectuals and intellectual movements that inspire me are those that showed me how to detect the undetectable. Walter Rodney is a key inspiration. His “groundings” method forged in Jamaica’s “gullies” was an early seed in how to go to the people if you want your eyes opened. Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones are Not Yet Born remains an exemplar in detecting the undetectable. Archie Mafeje, Frantz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, CLR James, Paulo Freire, Nzongola-Ntalaja, and Sylvia Wynter are remarkably important in showing how to “read” oppression. The work of Bronislaw Malinowski (when/if it can be stripped of its colonial anthropology) and Ludwig Wittgenstein has had a formative influence in how I approached induction and meaning.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

The work of CY Thomas and George Beckford (both from the Caribbean) is not new, but I have only recently got acquainted with it, and will certainly incorporate its insights in Volume 2, 3, and 4 of Apartheid Studies: A Manifesto. Thomas and Beckford’s work on the poor and on the plantation, along with various other texts, has utility for how I frame the oppressed as shock absorbers of the world and as “the wealth of nations”, particularly in my discussion of how apartheid is the highest stage of oppression which incorporates “household expenditure” as a critical dimension in the maintenance and persistence of oppression. Much of my future work in Apartheid Studies will be expanding on the 136 constructs introduced in volume 1 of Apartheid Studies: A Manifesto while also testing the framework in Brazil, the US, Canada, India, the Netherlands, UK, Kenya and Nigeria.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.