As part of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum, we interview scholars about a recent article they’ve written for either an academic journal or popular publication. We ask these scholars to discuss their article, as well as some of the books that have most influenced them.

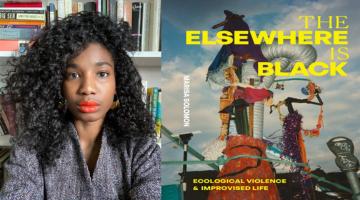

This week’s featured scholar is Brittany Meché. Meché is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Affiliated Faculty of Science and Technology Studies at Williams College. Her article is “Black as Drought: Arid Landscapes and Ecologies of Encounter across the African Diaspora.”

Roberto Sirvent: Can you please share what you mean by the idea of “Black as drought”?

Brittany Meché: The term comes from famed Black American poet Lucille Clifton. I use it in my article in two ways. First, I use it to index drought as an environmental hazard that disproportionately impacts communities of African descent, particularly on the African continent. Second, I also use it to describe how attending to the Blackness of drought, this disproportionate impact, allows for a different understanding of how communities live with and respond to environmental change. I’m working to make our conceptualizations of drought more capacious. It’s not just about reductions in rainfall or about lowered water tables, but it’s about capturing how drought functions as a feature of Black life past and present. And then from there, strategizing how to respond to experiences of drought in ways that privilege Black/indigenous knowledge systems and networks of mutual aid and diasporic solidarity.

Why is an understanding of colonialism and neo-colonialism so important for discourses around Black/African ecological thought?

You can’t understand our ecological present without accounting for histories of colonialism and ongoing forms of neo-colonialism. It’s not a coincidence that the countries most responsible for climate change are current and former colonial powers (the United States, countries in Western Europe). These countries built their wealth on the literal backs of peoples of color and inaugurated forms of resource extraction predicated on environmental ruin. Black/African ecological thought names and analyzes these processes, but it also helps us envision something else. Many of the writers and artists I discuss in my article, for instance Nnedi Okorafor, Tanure Ojaide, and Wanuri Kahiu, use traditions of Black/African storytelling and worldmaking to imagine other ways of being in relation to non-human entities and environments. Both pieces of this tradition are important for me: Naming the legacies of violence and exploitation and re-imagining how the world could be different.

How do Afro/Africanfuturists texts inform your work around global Black ecologies?

Afro/Africanfuturism is having a renaissance moment right now, and I think for good reason. It partly stems from people looking around and thinking, “This can’t be it. There have to be other kinds of futures.” I think strains of Afro/Africanfuturism, whether written stories, music, multimedia art work, offer comfort and inspiration. I also think these traditions are especially affirming amid so much suffering and death, particularly highly publicized and hypermediated circulations of death, from police body camera footage to news reports of communities devastated by (un)natural disasters. I think of the work of artist Alisha Wormsley, who did a now famous installation declaring “There are Black people in the future.” Just that simple assertion fights back against racist, white supremacist fantasies, that have existed for centuries, predicting the inevitable end to Black peoples. To insist—and set about doing the work to ensure—that there is a future where Black/African peoples can live and thrive is a radical act.

You teach a class at Williams College called “Science and Militarism in the Modern World.” What role does U.S. militarism play in fueling the ecological crisis?

It’s a complicated dynamic. One of the things that students are surprised to learn in that class is the reason we know climate change exists, as a series of global, macro-level changes to the Earth’s climate, is because following WWII the US government poured billions of dollars into environmental science. The Cold War state essentially created the institutional infrastructure that allows us to conceptualize and document the extent of climate change. But equally important, the US government is the largest historical emitter of global greenhouse gases (GHGs), the US military is the largest single institutional emitter of GHGs, and US imperial militarism has created ecological hazards and vulnerabilities at home and abroad. There’s a new book by Neta Crawford (The Pentagon, Climate Change, and War: Charting the Rise and Fall of US Military Emissions) that traces some of this history. For my own work, I’m also interested in how investments in militarized solutions to climate change are crowding out considerations of equity and justice. For instance, I conduct research in the West African Sahel, and I’ve written (“Bad Things Happen in the Desert: Mapping Security Regimes in the West African Sahel and the ‘Problem’ of Arid Spaces”) about how the US and France funded and trained local militaries and security forces as a way to assert order and stability amid political upheaval and ecological changes. In my work, I frame this as a preference for environmental security rather than environmental justice.

A lot of organizers, artists, and academics can often point to books that helped radicalize them. Are there any books that radicalized you? How so?

I came to this work through reading. Political education is essential for building movements. I always begin with The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon. I remember reading it as a teenager and the feeling was electric, like the words were jumping off the page. It’s a book that still feels urgent more than half a century later. Black feminist writers continue to radicalize and steady me. In moments when I’ve felt lost, frustrated, cynical, or defeated I’ve turned to books by Toni Morrison (Sula, A Mercy), Saidiya Hartman (Lose Your Mother, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments), Ruth Wilson Gilmore (Abolition Geography), and Farah Jasmine Griffin (Read Until You Understand).

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these works in your future scholarship?

Two books that I’m sitting with and working through right now are Abolition. Feminism. Now by Angela Davis, Gina Dent, Erica Meiners, and Beth Ritchie and Dear Science and Other Stories by Katherine McKittrick. The first is an important history of abolition as a contested series of movements and campaigns, successes and failures. In my own work, I’ve been fascinated by the ways geographers and other environmental scholars have tried to bridge these histories of abolitionist thought with building different kinds of ecological futures, what Megan Ybarra and Nik Heynen call “abolition ecologies.” McKittrick’s book is such a beautiful dismantling of multiple academic genres. It also re-imagines the epistolary form. The text provides a haunting indictment of what science has wrought, but it remains committed to advancing new forms of living. At one point, McKittrick states “Discipline is empire.” For my own work, it makes me re-consider the ways I’ve been disciplined into specific modes of thinking and writing. It’s a reminder to be more audacious with my own thinking and writing.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.