The online aggregation and coherence of Blackness online, absent Black bodies, is what inspired the author’s book.

“Black folk have a natural affinity for the internet and digital media.”

The following is an excerpt from André Brock Jr.’s book, Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. It is re-printed with permission from NYU Press.

The Black body has long been a feature—and Shibboleth—of articulations and theorizations of Black culture.1 The materiality of the Black body is easily understood as a benighted canvas for the iniquities and oppressions levied upon it, but its materiality has also led to elaborate, strained, scientific rationales about the legitimacy of race as a social construct. When scholars first sought to understand information technology use by Black folk, the Black body was only legible through its perceived absence: absence from the material, technical, and institutional aspects of computers and society. Over the last half decade, however, Black digital practice has become very much a mainstream phenomenon, even if its expert practitioners rarely receive economic compensation for their brilliance or political compensation for their activism.2 But online identity has long been conflated with whiteness, even as whiteness is itself signified as a universal, raceless, technocultural identity. By this I mean that whiteness is what technology does to the Other, not the technology users themselves. The visibility of online Blackness can be partially attributed to the concentration of Black folk in online spaces that are not exclusively our own; we are finally present online in ways that the mainstream is unable to disavow. Imagine, if you will, millions of Black people interacting through networked devices—laptops, computers, smartphones—at once separate and conjoined. This online aggregation and coherence of Blackness online, absent Black bodies, is what inspired this book.

I titled this book Distributed Blackness to evoke how Blackness has expertly utilized the internetwork’s capacity for discourse to build out a social, cultural, racial identity. Black online culture and sociality are more easily visualized today thanks not only to the hashtag and other algorithmic means but also to the near infrastructural use of social networking services as well as older online artifacts, such as messaging services, blogs, and bulletin boards, where one could see articulations of Black identity across digital networks. My subtitle, African American Cybercultures, speaks to this text’s theoretical and rhetorical thinking about how and why Blackness and Black culture are easily and pungently performed, absent embodiment, when mediated by technologies—specifically information technologies, the online, and the digital.

“Online identity has long been conflated with whiteness, even as whiteness is itself signified as a universal, raceless, technocultural identity.”

Distributed Blackness is also a reference to the methodology used throughout this text: critical technocultural discourse analysis (CTDA). I devised CTDA as a corrective to normative and analytic research on cultural digital practice. It decenters the Western deficit perspective on minority technology use to instead prioritize the epistemological standpoint of underrepresented groups of technology users. CTDA pulls together multiple disparate data points to conduct a holistic analysis of an information technology artifact and its practices. Distributed here refers not only to CTDA’s analysis of discourses across websites, services, and platforms—published by the technology’s users about their wielding of the technology—but also to its holistic approach to analyzing technology as discourse, practice, and artifact. This approach lends CTDA analytic power to understand how digital practitioners filter their technology use through their cultural identity rather than through some preconceived “neutral” perspective.

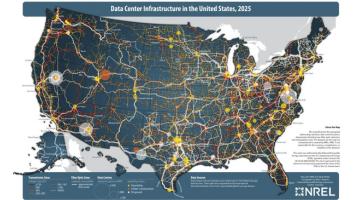

Finally, Distributed Blackness is a callback to one of the first cultural networked informational Black artifacts: The Negro Motorist Green Book (Green, 1941). On first glance, the Green Book is just a book—a directory of Black businesses published by Blacks for Blacks long before the internet. Hall (2014) argues for the Green Book as a tool to resist postcolonial and postbellum legacies of white racial violence and hegemony (pp. 307–319). I agree but insist that the Green Book should also be viewed as one of the first cultural network browsers. The network in this instance was the US highway system—a developing infrastructure tailored for the exponentially growing numbers of automobile owners. As early as the 1910s, Black drivers saw automobile ownership as a pathway to personal mobility and technological expertise and as a signal of belonging to the middle class, with the attendant properties of racial uplift ideology (Franz, 2004, pp. 131–153). Moreover, one of the hallmarks of post–World War II life in the United States was the spread of “leisure” as an outlet for relaxation, and Blacks were just as eager to share in it as any other American. Like many whites, Blacks began to consider cross-country driving as not only a pathway to leisure activities but also a way to return to their ancestral homes in the South following the Great Migration’s dispersal of Black families across the United States.

“The Green Book should also be viewed as one of the first cultural network browsers.”

In doing so, however, they had to traverse entire states—particularly in the Midwest, where “sundown towns” were most prevalent (Loewen, 2005), but also in the West and Northeast, where local Blacks were mired in state-sanctioned Jim Crow violence and customs. Imagine, then, in spaces where Blacks were already discriminated against, the arrival of affluent “foreign” and unfamiliar Blacks looking for sustenance, fuel, or just a chance to rest. The Negro Motorist Green Book was precisely designed to provide these highway “browsers” with a guide to safe spaces that would welcome weary Black travelers and vacationers.

First published in 1936 by Victor Green and continuing through 1967 (albeit under a different name), the Green Book featured information garnered from those who drove across the country by necessity: salesmen, athletes, clergy, and entertainers. This singular Jim Crow–era periodical helped Black folk navigate America’s roads by annotating safe waypoints and destinations. It was distributed in part by the United States Travel Bureau and, crucially, by the Standard Oil Company, lending the Green Book a national audience. Eventually, the book listed resources available to traveling Blacks across the continental United States as well as locations in Canada, Alaska, the Caribbean, and Mexico.

Arguing for the Green Book as an example of distributed Blackness—an informational artifact linking Black information seekers to Black cultural resources across a network—then, seems like a no-brainer. The Green Book was the Google (or more appropriately, the Yahoo! Open Directory Project of Black information, since the directory was human-reviewed rather than algorithmically determined) of its time, a search engine for those seeking culturally vital information. These resources, catering to the needs and wants of a technologically enabled mobile Black community, were distributed unequally across the network. Even as highways and driving were increasingly promoted as “quintessential American” activities, Blacks were often excluded from enjoying them in the same way. The Green Book imagined the US highway system as a Black technological network—not as an Afrofuture but as a present-day marvel containing possibilities for joy and for violence—that performed resistance alongside Blackness as the capacity to enjoy leisure even as urban renewal projects used the construction of interstate highways as a means to destroy vibrant Black urban communities. While the internet doesn’t offer the same physical potential for discrimination and racist violence against Black folk, there is still a pressing need for the curation of digital and online resources for Black folk seeking information and “safe spaces.” These spaces range from portal websites like Everything Black, to bulletin board websites like Nappturality, to the pioneering gossip blogs Crunk and Disorderly and Concrete Loop, to the Blackbird browser, to upcoming efforts to create mobile apps. In short, networked information—in the form of resources for identification, community, self-defense, joy, resistance, aesthetics, politics, and more—is essential to Black online identity. How, then, do the internet and digital media mediate Blackness?

“The Green Book imagined the US highway system as a Black technological network.”

The possibilities of Black digital identity, Black digital practices, and Black digital artifacts first came to me upon reading Miller and Slater’s (2000) ethnographic study of Trinidadian internet users. Trinidad and Tobago—a polyglot former English colony in the Caribbean inhabited by people of African, indigenous, Indian, Chinese, and white descent—while tiny, has an immense diasporic population across North America and Europe, yet this has done little to diminish the diaspora’s national and ethnic identity. Over the course of their eleven-year study, Miller and Slater found that the internet became an expression of Trinidadian identity. This finding was (and still is) in direct contrast to bromides about technology forcing users to adapt to mainstream culture and also counters long-standing deficit-based beliefs about people of color and information technologies. Instead, the Trinidadians found ways to make the internet Trinidadian in thought and in deed. Miller and Slater write, “Trinidadians have a ‘natural affinity’ for the internet. They apparently take to it ‘naturally,’ fitting it effortlessly into family, friendship, work and leisure and in some respects they seemed to experience the internet as itself ‘naturally Trinidadian.’ . . . It provided a natural platform for enacting, on a global stage, core values and components of Trinidadian identity” (p. 2).

This revelation of nonwhite culture manifested through information technology was mind-blowing to me in the era of the digital divide, when many argued that Black Americans were technologically and computationally deficient. The lessons I learned from Miller and Slater, then, are equally applicable to African American uses of information and communication technology: Black folk have a natural affinity for the internet and digital media.

By natural, I am by no means arguing that internet use is an “essential” quality of Blackness. Essentialism, for nonwhites, has a long, pejorative history within Western culture; only nonwhite bodies suffer reduction to a perceived intrinsic characteristic. Instead, my claim is pragmatic; Black expressivity is rightfully lauded in literature and in art, but Black linguistic expression is denigrated in modern (i.e., technical and professional) society. Indeed, Black identity is associated with many things, but the internet—or more specifically, the expertise in information and communication technology practice—is not usually one of them. My claim is ecological: Black folk have made the internet a “Black space” whose contours have become visible through sociality and distributed digital practice while also decentering whiteness as the default internet identity. Moreover, I am arguing that Black folks’ “natural internet affinity” is as much about how they understand and employ digital artifacts and practices as it is about how Blackness is constituted within the material (and virtual) world of the internet itself. I am naming these Black digital practices as Black cyberculture.

Notes

1 Throughout the text, I oscillate between Black and African American to refer to Black American culture. I am aware that diasporic African cultures in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America share some of the same beliefs and practices discussed here. Moreover, many African and indigenous ethnicities also have contributed values, language patterns, and aesthetics to what I am arguing here for as Blackness.

2 No shade to Deray Mckesson.

André Brock, Jr. is Associate Professor of Black Digital Studies at Georgia Institute of Technology.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com