Much of what is called the “left” still insists that the American “revolution” of 1776 is “unfinished,” when history shows that white supremacy was the intended result.

“Those who consider themselves to be sophisticated refer to an ‘Incomplete Revolution,’ as if the founders had in mind ‘others’ not defined as ‘white’ but, perhaps, forgot to include them.”

In “The White Republic and The Struggle for Racial Justice,” Bob Wing contended that the U.S. state is racist to the core, and this has specific implications for our movements’ work going forward, especially the need to replace this racist state with an anti-racist state. Organizing Upgrade is publishing a series of commentaries on this piece, and we invite readers to respond as well. In this installment, Gerald Horne argues that we must reckon with the dynamics of settler colonialism if we are to understand white supremacy. “The attempt to build ‘class unity’ without confronting these underlying tensions often has meant coercing oppressed nationalities—Blacks in the first place—to co-sign a kind of ‘left wing white nationalism,’ Horne writes.

The good news is that Comrade Bob Wing’s analysis represents a step forward in terms of the U.S. Left’s understanding of the nation—“republic”—in which it struggles.

The bad news is that the U.S. left has not necessarily kept pace with the U.S. ruling class in terms of similar issues, or even with non-radical African-Americans, for that matter.

Consider the multi-part series on HBO Max (a member in good standing of the much reviled “corporate media”) that premiered recently, i.e. Black filmmaker Raoul Peck’s “Exterminate All the Brutes,” a sweeping analysis and condemnation of settler colonialism (a term curiously absent from ordinary discourse on the left) and white supremacy. His other credits include the superb docu-drama “The Young Karl Marx.”

Consider the 1619 Project of The New York Times, spearheaded by Black journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, which—inter alia—had the audacity to suggest that a settlers’ revolt in 1776 led by slaveholders may have had something to do with maintaining slavery. Revealingly, the assault on this estimable initiative was mounted by self-described “socialists”, liberals and conservatives: in essence, The White Republic.

Consider the book by Black scholar Tyler Stovall (published by an Ivy League press), White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea, which is more advanced ideologically than comparable analyses on the U.S. left.

Consider the response to the concerted effort to deodorize the smelly roots of the vaunted “Founding Fathers”: I speak of the Broadway/Disney extravaganza, “Hamilton,” celebrated by the Cheneys and Obamas alike, not to mention some to their left—but skewered by paramount Black intellectual, Ishmael Reed.

How and why the U.S. left has tailed the ruling class on such a bedrock matter as conceptualizing white supremacy soars far beyond the confines of this brief response. Suffice it to say for now that misconception begins with the origins of the slaveholders’ republic in 1776, a creation myth that Comrade Wing does not challenge explicitly. Those who consider themselves to be sophisticated refer to an “Incomplete Revolution,” as if the founders had in mind “others” not defined as “white” but, perhaps, forgot to include them. This is akin to referring to implanting apartheid in 1948 as an “Incomplete Reform,” as if these founders, perhaps, forgot to include Africans in the bounty that was accorded to poorer Afrikaners. Even the supposedly perceptive term “bourgeois democracy” as a descriptor for 1776 and its fruits is misleading at best since “rights” definitely did not include any not defined as “white” and, thus, this term becomes part of the massive misdirection that now has us on the brink of fascism.

Settler Colonialism and the Construction of Whiteness

First, consider the confluence of settler colonialism and the construction of “whiteness.” When settlers arrived in what is now North Carolina in the 1580s it was a multi-class venture—shopkeepers, smiths, etc.—sponsored by the London elite. This was in the midst of religious wars between Catholics and Protestants. Catholic Spain, which came within a whisker of toppling the London monarchy in 1588, imposed religion as a qualifier for settlement. England, the scrappy Protestant underdog, moved toward Pan-Europeanism—or “whiteness”—incorporating Scots and Irish and Welsh in the first instance, those with whom they had been warring for centuries, and then moved toward incorporating others who had been warring: British v. German; German v. Pole; Pole v. Russian; Serb v. Croat—the list is long. All of a sudden when crossing the Atlantic, in a manner that would make Madison Avenue blush, all are rebranded as “white,” which subsumes many of the tensions, ethnic and class among them, in a new monetized and militarized “identity politics” of “whiteness” based on expropriation of the Indigenous and mass enslavement of the Africans.

As the 17th century roots of Maryland suggest, London was willing to sponsor Catholic settlers, while inquisitorial Madrid continued to bar and expel those not deemed to be religiously correct. Thus, from the inception in the early 1500s, Havana contained African conquistadors who professed Catholicism (a sharp divergence from racialized settlements in the “Anglo-sphere”, leaving a legacy which continues to wrongfoot those seeking to comprehend socialist Cuba) and as late as 200 years ago, settler Stephen F. Austin professed a nominal Catholicism in order to engage in his land grab in Mexican Texas.

Of course, Ottoman—and heavily Islamic–Turkey was an igniting factor in this process. Their seizure of what is now Istanbul in 1453 impelled an existential crisis in Western European Christendom: as Columbus headed westward in 1492, on behalf of Catholics he was seeking to circumvent the Ottomans; 1492 also marks the accelerated weakening of Islamic rule in Iberia, followed by many fleeing to North Africa and to Ottoman jurisdiction, along with the Jewish minority.

Tellingly, London had expelled its own Jewish minority circa 1290-1291 but in the contestation with Catholics, this Protestant power embraced this minority—as did Protestant Holland—and the victorious republicans did so too by 1776. The philosophically idealistic and credulous tried to convince the rest of us that this was a result of “Enlightenment,” as opposed to seeking to broaden the base of settler colonialism in order to confront obstreperous Africans and the mighty Indigenous.

Interestingly, in the late 1930s, the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo also embraced a fleeing European Jewish minority and only the naïve would ascribe this decision to “Enlightenment”—as opposed to a crude attempt to “whiten” the population in the ongoing conflict with the bête noire that was neighboring Haiti, whose nationals were simultaneously being massacred along the border.

Speaking of neighbors, it is similarly informative that patriotic U.S. analysts of the left generally refuse to scrutinize the “control group” due north. Canada did not rebel against London and yet now has a health care system that is the envy of the so-called “revolutionary republic”—should not one expect the opposite?

Actually, settlers’ revolts—be they in Southern Rhodesia in 1965 or Algeria in the late 1950s—are generally problematic, especially when driven by white supremacy and/or religious bigotry. To the “credit” of the North American settlers’ revolt, unlike their French counterparts in Algiers, they were not as advanced in seeking to liquidate the monarch himself, as was the case in Paris in April 1961 with Charles de Gaulle in the crosshairs. (For the naïve who continue to guzzle the Kool-Aid and propaganda of “liberal democracy,” on the 50th anniversary of this plot, French military men threatened a coup against President Macron, just as the elite U.S. publication Foreign Affairs reported a disturbing trend of the military bucking civilian rule: see also 6 January 2021 and the recent open letter signed by dozens of retired military brass in the U.S. echoing MAGA talking points and warning ominously against the purported “socialism” of the current regime in Washington.)

Given the troubling roots of this republic, it was inevitable that at a certain point what are described as “cultural” issues—immigration; reproductive and LGBTTQ rights—would leap to the fore as these are perceived as natal matters essential to an apartheid state: maintaining a presumed “white” majority.

Left-Wing White Nationalism

This transition from religion to “race” was occurring in the context of a bumpy transition from feudalism to capitalism. “Bloody Mary,” the English monarch in the mid-16th century, received her moniker as a result of reports of Catholics burning Protestants at the stake. Unsurprisingly, as capitalism attained liftoff as a direct result of the plunder of the Indigenous and the mass enslavement of the Africans, by the end of the 19th century, Africans were being immolated (in enslaved form representing the essence of capitalism)—with either Catholics or Protestants of European descent, often of British origin (at times jointly) lighting the torch.

The attempt to build “class unity” without confronting these underlying tensions often has meant coercing oppressed nationalities—Blacks in the first place—to co-sign a kind of “left wing white nationalism,” as reflected in the lengthy attempt to convert slaveholder, Thomas Jefferson, into a unifying symbol. Black failure to do so leads to our denunciation—in today’s terms as “identitarian” [sic], in previous decades, as “narrow nationalist.” Actually, the class collaboration embodied in “whiteness” was seeking to impose “class collaboration” on the descendants of the enslaved, inducing us to align with enslavers and their descendants. And given that pre-1865 U.S. history—and to a degree the era thereafter—involved deputizing Euro-American settlers as a class to patrol and coerce the Indigenous and the Africans, this too involved an often undetected class collaboration. It also involved often lush material incentives for those settlers who complied and harsh disincentives for those who did not.

In sum, unlike Raoul Peck, the U.S. left parachuted into the 20th century and sought to impose an ersatz “class unity” brutally at odds with historical reality. They were akin to cineastes entering the theatre halfway through the film, while thinking they had a firm grasp of the plot. Indeed, Peck’s work and that of other Blacks represents an attempt to wrest the powerful searchlight of Marxism away from those who have strived to convert it into a feeble flashlight.

When reality does not correspond to the facts on the ground, the U.S. left often responds like the fictional French intellectual who maunders: “I know what you are saying is true in fact, the question is—‘is it true in theory?’” That is, a detailed knowledge of history and contemporary trends is the meat to be placed on the skeleton that is theory—without that meat one is left with a putrefying cadaver.

Thus, when Euro-Americans vote across class lines for faux billionaires, we are instructed that the reason is that the opposition did not meet their exacting progressive standards—hence, they voted for the right. (Once when I was explaining to a prominent left-leaning scribe that the citadel of the elite, the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and the citadel of the Euro-American working and middle classes, Staten Island, are the bastions of the right wing in Gotham, he demurred seeking to point out that the latter borough voted thusly because of liberal failings: and, yes, he had never heard of John Marchi, Staten Island’s decades long proto-fascist GOP boss, re-elected repeatedly.) Of course, this miscomprehension begs the question as to why descendants of the enslaved even in the same borough and nationwide – marinated in the ultimate class struggle of slaves versus slaveholder – vote against the right wing in extraordinarily high numbers.

This misanalysis also neatly elides the instructive 1991 gubernatorial election in Louisiana when well over half of Euro-Americans across class lines voted for a Nazi and Klansman, David Duke, for governor—who would have prevailed but for the staggering blow delivered to his onrushing campaign by the mailed fist that was the Black vote.

Forge Alliances Beyond US Borders

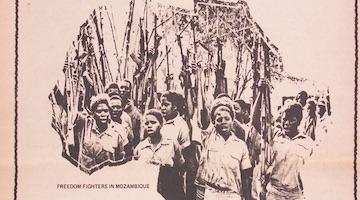

African Americans in particular sliced neatly the Gordian knot of oppression historically by forging alliances beyond the confines of settler colonialism, with ties to the Indigenous (e.g. antebellum Florida) or Haiti (post-1804) or London (1776-1865) or Tokyo (pre-1945) or Moscow (post-1917) or independent Africa and the Caribbean (post-1960).

What does this mean for today? It means rejecting the new Cold War against Russians and Chinese and, instead, forging alliances with both. It means linking demands for reparations nationally with likeminded struggles in the Caribbean and Africa. It means realizing that the uncanny ability of some on the U.S. left to hand rhetorical weapons to the right to bash the oppressed – from “political correctness” to “cancel culture” – is hardly a coincidence or accident but simply another expression of a “cross-class alliance” that has propped up settler colonialism from its inception. (Truth be told, these weapons were honed principally by “white” leftists in internecine conflicts that led – objectively and unsurprisingly – to a dearth of questioning of the legitimacy of settler colonialism.) It also means forcing class initiatives as a solvent against the pestilence that is white supremacy – for example, the PRO law or right to organize unions, now before Congress.

Per Comrade Wing, it also means seeking to deepen our understanding of the fundamentals of U.S. imperialism, white supremacy not least. Congratulations to Comrade Wing for seeking to rescue virtually every sector of the “radical” U.S. left from a swamp of Right Opportunism.

Gerald Horne, lawyer and historian, is the author of dozens of books on slavery, socialism, popular culture and Black Internationalism, including ‘The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism and Capitalism in the Long 16th Century‘ (Monthly Review Press, 2020) and ‘ The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the USA’, (NYU Press, 2014). Horne currently holds the John J. and Rebecca Moores Chair of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston.

This article previously appeared in Organizing Upgrade.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com