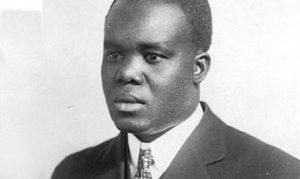

Hubert Henry Harrison was one of the foremost Black socialist and nationalist thinkers of the early 20th century. He was known as "the father of Harlem radicalism." This is the last of a three-part commentary on works about Harrison.

The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1927

The most recently published second volume Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1927 covers the last 10 years of his life during which he continued as a leading voice in the New Negro Movement based in Harlem and reached national and international audiences through speaking tours and publications he either founded or edited. These include The Voice, The New Negro magazine and the The Negro World.

Perry devotes more than half of the second volume to a very detailed, well documented examination of Harrison’s relationship with Marcus Garvey, The United Negro Improvement Association, Black socialists, communists and the disputes, alignments and realignments that have framed the modern race/class conundrum in the US since World War 1.

If A Hubert Harrison Reader and the first volume, The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 grew out of Perry’s first encounter with Harrison’s writings in the 1980’s, his determination to produce a two-volume biography came after Aida Harrison Richardson, Hubert and Irene’s third daughter, gave Perry her father’s diaries, now archived at Columbia University.

To summarize the 800 pages of the second volume is clearly impossible, but suffice it to say that the disputes among Harlem radicals that emerged between 1918-1928 may help to explain why Harrison’s leading role in the New Negro Movement was largely excised from academic accounts. Harrison was in the middle of these controversies. His criticisms of Booker T Washington incurred the wrath of the Tuskegee machine. After his criticism of W. E. B. Du Bois’ “Close Ranks” article, Du Bois never mentioned Harrison by name again opting instead to refer only to that certain “Negro writer.” Harrison had refused to join the chorus of Black socialists, who opposed Garvey from the start. While managing editor of the Negro World Harrison refused to be the communist party’s stalking horse against Garvey even though in his diary he was very critical of Garvey following the 1920 UNIA convention. Given that debates over strategy and tactics within the Black and radical community continue today, Harrison’s views on the centrality of race in the US and on leadership in the struggle for equality between 1918-1927 seem prescient in hindsight.

In the first volume, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, Garvey was a newcomer to Harlem when Harrison first introduced him to a Liberty League gathering on June 12, 1917 at Harlem’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Disputes soon arose in the Liberty League and The Voice over whether to accept “white” financial support or to rely exclusively on support from the Black community. Harrison, like Garvey, favored Black money over ‘white” money but Harrison at the same time refused to accept advertisements from skin lighting creams or hair straightening products that typically helped to support other Black periodicals. Additionally, Harrison maintained total editorial control over the Liberty League publication, The Voice, opposing those in the organization who favored shared decision making. Perry notes also that Harrison apparently did not manage money well, typically overspent and was also having some health issues.

Without a secure personal income or institutional supports, Harrison, Irene and their children often found themselves in dire financial straits. In addition to financial troubles there was the marital stress that resulted from Harrison’s infidelities. Irene “Lin” Harrison does not appear to have left any written record of her own, but Perry recounts some conflicts recorded by Harrison in his diary and personal papers.

While a member of the Liberty League, Garvey honed his oratory, adopted much of the Race First program that Harrison had promulgated and offered what appeared to be a solution to the funding quandary. Garvey was able to raise large sums of money from the Harlem community through his sale of stock and bonds to launch what he promoted as Black owned enterprises, most notably, The Black Star Line.

In the process Garvey won some of Harrison’s close associates over to his own United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Edgar Grey, former officer in the Liberty League became the General Secretary of the UNIA. W. A. Domingo, another Liberty Leaguer, became the first editor of the Negro World.

Garvey’s sale of bonds initially for a restaurant and grocery store and later the Black Star Line came under scrutiny in 1918 following allegations of fraud by investors. An audit committee, whose members were selected by Garvey, claimed mismanagement of the funds raised for both the UNIA and The Black Star Line and that the money had been raised under false pretenses. By 1919 Grey, General Secretary of the UNIA, Richard Warner, Executive Secretary of the UNIA and Secretary of the Black Star Line, and W. A. Domingo, Editor of the Negro World, had all resigned their positions. Lawsuits and counter suits ensued and the New York City Assistant District Attorney ordered Garvey to stop selling bonds. Garvey for his part continued to raise large sums of money from trips outside of New York for support for the Black Star Line.

Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) had combined much of the “Race First” program of the Liberty League with what appeared initially to be a bold vision of economic independence for a Black led, mass-based organization. Garvey assumed a leading role in Harlem despite increasing public criticism, lawsuits from investors and resignations of former Liberty League members. In the face of growing challenges to his credibility, Garvey turned to Harrison and offered him work as essentially the effective Managing Editor of the Negro World in early 1920.

Harrison’s acceptance of Garvey’s offer came at a point when the Liberty League and The Voice had ceased to exist. Harrison had no job or means of support for his growing family and Garvey offered him a decent salary and editorial freedom to carry on what he had started with the Liberty League and The Voice. Harrison’s acceptance added credibility to Garvey’s efforts but gave rise to a vituperative public war of words with his former socialist and Liberty League comrades who had emerged as sharp critics of Garvey. Harrison defended himself for taking the job as Managing Editor of the Negro World, and his decision to join with a mass movement that the Liberty League and The Voice had essentially paved the way for. He refused to join in the public criticism of Garvey’s and he in turn publicly derided Garvey’s critics as “Just Crabs.” He contrasted the mass movement based on the Africa First approach which had been adopted by Garvey, with the meager support garnered by the socialists.

Under Harrison’s editorial control, the Negro World achieved international circulation and self-sufficiency with over 50,000 paid subscribers. He was however under no illusions regarding Garvey’s shortcomings as a leader. Following the 1920 UNIA convention Harrison began efforts to seek out ways to restart The Voice and organize a Liberty Party, efforts which however came to naught. At this time Harrison published When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” on the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World which was used as a training manual for the United Negro Improvement Association and was sold in Harlem barbershops.

Harrison noted in his diary that Garvey promoted fanatical devotion and was given to self-aggrandizing and bombastic statements. Harrison, nevertheless, went about the job of turning the Negro World into a self-supporting publication with a worldwide readership.

Garvey’s fundraising schemes however increasingly were revealed to be fraudulent and he was embroiled in numerous lawsuits. Harrison distanced himself from Garvey. His position at the Negro World went from Managing to Contributing Editor to contributing writer and ended in 1922.

As criticism from within the Black community and criminal investigations grew, Garvey and some of his more fanatical supporters employed increasingly repressive measures to intimidate critics and block prosecution. W. A. Domingo was assaulted by Garveyites. A tent revival meeting sponsored by the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr. was broken up by a few hundred Garvey supporters. W. E. B. Du Bois received threatening letters after criticizing Garvey. In September 1922 a human hand cut off below the wrist was mailed from New Orleans to A. Philip Randolph with a letter allegedly from the KKK ordering Randolph to join the UNIA. This occurred three months after Garvey had met with the KKK in New Orleans and expressed his support for racial segregation. Four months later The Reverend James Hood Eason, a prominent leader in the UNIA who broke with Garvey and was the leading witness for Garvey’s prosecution was murdered in New Orleans by Garvey supporters shortly before he was to testify in early 1923.

By 1923 Garvey had been found guilty of fraudulent use of the mails and was deported shortly thereafter. Harrison’s account of the trial in “Marcus Garvey at the Bar of United States Justice” (“Associated Negro Press,” July 1923) is reprinted in A Hubert Harrison Reader in which he described Garvey’s trial as “fair.” In his diary Harrison wrote that Garvey could have been prosecuted for far more serious crimes than mail fraud.

International Colored Unity League Between 1924-1927 Harrison worked to establish the International Colored Unity League (ICUL), the program for which is included in A Hubert Harrison Reader and which includes a demand for a Negro state (four years before the Communist party would adopt its Black Belt Nation thesis). He went on a speaking tour in Massachusetts for the ICUL and wrote a regular column, “Trend of the Times” for the Boston Chronicle.

Harrison’s article on the Lafayette Theatre strike, “How Harrison Sees It,” was published by the Amsterdam News (10/6/1926) and a lengthy quote appears in the second volume of the Harrison biography. The Lafayette Theatre strike divided Harlem radicals and was a central issue for Harold Cruise in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. As Harrison saw it “…unlike Abraham Lincoln, my prime object was not to save the union but to free the slave.”

He edited The Voice of The Negro, was a lecturer for the NYC Board of Education and collaborated with Arturo Schomburg on the establishment of what would later become the Schomburg Library. Harrison also published widely including “The Real Negro Problem” for The Modern Quarterly in which he considered “the conditions under which the relations between the black and white races were established in America.” Over the summer of 1926 The Institute for Social Study hosted a 10-lecture series in Harlem offered by Harrison entitled “World Problems of Race.”

Conclusion

In the epilogue to Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1927, Perry reviews the comments, obituaries and memorials that followed Harrison’s premature death in 1927 at the age of 44 from complications following an appendectomy. Over 1,000 people attended the funeral. Among the pallbearers were Arturo Schomburg and Richard B Moore who would lead the international defense of the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930’s.

The heroic aspect to the biographies and A Hubert Harrison Reader that highlight his remarkable talents and achievements are balanced by Harrison’s own diary entries in which we get a glimpse of the stresses and strains that activism, poverty and male privilege imposed on the growing Harrison family. Irene “Lin” Harrison worked during this time as a seamstress while caring for the children. Harrison activities took him far afield from the day to day responsibilities of raising a family and into a series of affairs with other women. Harrison was “irrepressible,” but neither perfect nor physically immune to the wear and tear of leadership and poverty.

Harrison and his family were part of the Harlem community from which emerged a new movement that aimed to stop and reverse the erosion of the gains of the Civil War and Reconstruction. The movement promoted self-reliance, self-respect and was internationalist in so far as it viewed itself as linked with the anti-colonial movements emerging in Africa, the Caribbean and Asia.

“Tell me whose bread you eat and I will tell you whose song you sing.”

The enduring significance of Harrison’s contributions for activists today may be his vision and tireless efforts to base organization of the overwhelmingly working class Black community on the people themselves.

The old aphorism, “Tell me whose bread you eat and I will tell you whose song you sing,” was frequently referenced by Harrison and underlay his frank assessment of contemporaries who in his view had strayed from the path. His critical remarks were sometimes heated but in the main not mean spirited or motivated by jealously or spite. A controversial figure, Harrison’s frank assessments earned the respect of most contemporaries and the smoldering resentment of others whose pet projects and visions his remarks disturbed.

Today, as “McMovements,” NGO’s, non-profits, and the near complete corporatization of mainstream media and academia work to subsume and manage authentic expressions of popular discontent, Harrison’s radicalism is a refreshing reminder that, then as now, it is the people’s struggle that shapes history.

Sean I. Ahern is a retired NYC public school teacher, father, grandfather and husband. He was previously active in labor struggles in the Postal Service and NYC Transit Authority.