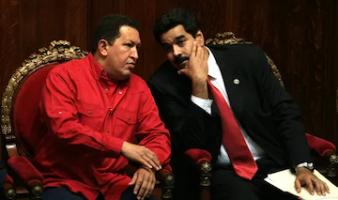

Haitian migrants, displaced by the 1991 U.S.-backed coup of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, line up at Guantánamo to be processed. Credit: The U.S. National Archives (public domain)

The threats by the Trump administration to detain migrants in Guantanamo Bay will not be the first time the United States has used the facility for migrant detention. Not too long ago, Haitian migrants were held in Guantanamo Bay and forced to live in inhumane conditions.

Originally published in Liberation News.

Trump’s plan to house 30,000 undocumented immigrants in Guantánamo Bay

On Jan. 29, the returning Trump administration instructed the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security to increase capacity at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base to hold 30,000 migrant detainees. Since the announcement, two U.S. military planes have transported undocumented migrants to the facility. The Trump administration plans to eventually send daily flights of migrants to the base for detention.

The Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs criticized the U.S. approach, claiming it reflects government brutality in addressing economic and social issues. They reiterated that the base is Cuban territory, illegally occupied by the U.S., and highlighted its history as a site of torture and indefinite detention without fair trial.

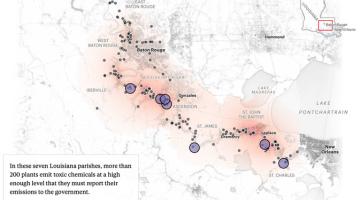

While many of us are familiar with the dark history of Guantánamo as a CIA black site used to interrogate and torture enemy combatants, few know that the base also holds a migrant detention facility where asylum seekers are forced to live in deplorable conditions “characterized by undrinkable water, exposure to open sewage, and poor medical care and schooling facilities for children.” In the 1990s, thousands of Haitians fleeing political violence in their country were sent to the military base for detention.

Guantánamo: A territory taken from Cuba by the U.S.

Guantánamo Bay was originally part of Cuba, a Spanish colony until the late 19th century. During the Spanish-American War (1898), the U.S. seemingly intervened to support Cuban independence but ultimately sought to expand its imperial interests. This marked the beginning of U.S. imperial dominance in the Caribbean.

After defeating Spain, the United States established a military presence in Guantánamo Bay through a perpetual lease in exchange for an annual payment. This lease was imposed on Cuba under military pressure, leaving the country with no choice but to comply with U.S. demands.

Following the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro’s government demanded the return of Guantánamo Bay, arguing that the lease was illegitimate and imposed under colonial conditions. Cuba cites the Platt Amendment — a treaty enacted during the U.S. military occupation that gave the United States the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and required Cuba to lease land to the U.S. for naval bases — to support its claim that the agreement was invalid. Today, Guantánamo Bay remains the only U.S. military installation in a socialist country.

History of sending Haitian migrants to Guantánamo

Detention of Haitian migrants at Guantánamo began in the 1970s when authorities under Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter intercepted their ships on the way to Florida and held them on the base for processing.

After the 1991 overthrow of Haiti’s democratically elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide by the U.S. government, around 40,000 Haitians attempted to flee to the United States. Many were detained at Guantánamo Bay for at least six months under deplorable conditions, where they faced inadequate supplies and poor living conditions. At its peak, more than 12,000 Haitians were detained at Guantánamo, waiting to be processed. Most were eventually sent back to Haiti, while some remained without the usual U.S. asylum protections.

Among the detained were individuals who tested positive for HIV. These individuals were segregated and held indefinitely without access to sufficient medical care or legal representation due to the fear surrounding the disease and legal changes that banned the admission of HIV-positive Haitians into the U.S. HIV-positive women, in particular, were often injected with Depo-Provera, a form of birth control, or even forcibly sterilized — usually without their consent or knowledge.

This situation left refugees with a grim choice: endure the harsh conditions at Guantánamo or return to a potentially deadly environment in Haiti. These inhumane conditions led to several forms of resistance: protests, riots, and hunger strikes were organized by the detainees, demanding better treatment and the right to seek asylum. U.S. authorities responded with severe repression, including physical assaults on the protesters.

During their detention, a few Haitians created paintings using available materials to depict their experiences, including their journeys at sea, the stigma of HIV/AIDS, and tributes to their lost loved ones and homeland.

In 2010, following a catastrophic earthquake in Haiti, Guantánamo was considered for holding refugees again. While a significant exodus didn’t occur, U.S. Air Force planes conducted daily flights over the devastated country, broadcasting a message in Creole from Raymond Joseph, the Haitian ambassador to the U.S.: “If you think you will reach the U.S. and all the doors will be wide open to you, that’s not at all the case.”

And as recently as last year, Joe Biden — in anticipation of the political turmoil following U.S.-installed leader Ariel Henry’s resignation — once again discussed detaining Haitian migrants at the military base.

US racist and imperialist foreign policies drive Haitians to migrate

Since Haiti’s independence, U.S. elites have had their sights set on the country, as it was forced to take out loans from the U.S. and other international banks to pay reparations to France following its struggle for independence, which established the first Black republic. In 1914, using the loan repayment issue as a pretext, U.S. Marines descended upon Haiti’s central bank in Port-au-Prince, seizing half the nation’s gold reserves and shipping it off to Wall Street. This turmoil in Haiti served as a justification for an all-out invasion by the U.S., which occupied the country for nearly two decades and reimposed forced, unpaid labor performed at gunpoint to construct a road system, ensuring military and commercial control for U.S interest.

Haitians have immigrated to the U.S. in significant numbers since the 1970s, many fleeing Haiti by boat and being derogatorily labeled as “boat people.” They escaped a brutal dictatorship led by François and Jean-Claude Duvalier, responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands and for imprisoning and torturing many others. Haitian refugees fleeing this regime coming to the U.S. often faced arrest, imprisonment, denial of asylum, and immediate expulsion.

Due to rampant anti-communism, the U.S. supported the Haitian government under the Duvaliers while simultaneously undermining and delegitimizing the Cuban government under Fidel Castro. This foreign policy shaped immigration policy, resulting in Cuban refugees being encouraged to come to the U.S. while Haitian refugees were denied similar amnesty. Multiple U.S. presidents upheld these immigration policies, influenced by anti-Haitian bigotry that perceived Haitian immigrants as a threat due to a mix of racism, nationalism, xenophobia, and the misconception that Haitians carried diseases at higher rates than other nationalities.

The U.S. also supported hyper-capitalism in Haiti. In 2011, WikiLeaks revealed that the Barack Obama administration and contractors for Fruit of the Loom, Hanes, and Levi’s collaborated closely with the U.S. Embassy in Haiti to agitate against and block an increase in the minimum wage for Haitian assembly —zone laborers, who earned less than 31 cents per hour — one of the lowest wages in the hemisphere. In line with industry practices, these brand-name U.S. companies kept their hands clean, allowing their contractors to ensure Haiti was safe for the sweatshops from which they derived profits — with assistance from U.S. officials.

To this day, the U.S. continues to fuel both physical and economic violence in Haiti. Most firearms and ammunition in the country come from the U.S. This context is crucial when considering the current situation in Haiti, which has displaced more than 360,000 people and leaving thousands homeless.

Racist, inhumane treatment of migrants is bipartisan

The Trump administration’s plan to detain 30,000 undocumented immigrants in Guantánamo Bay is not an abnormality but a continuation of the United States’ bipartisan imperialist policies, which have systematically destabilized nations in Latin America and the Caribbean and created the very conditions that force those people to migrate. This plan also highlights historical grievances over the illegitimate occupation of Cuban territory and the legacy of U.S. intervention in Haiti that has created a cycle of displacement and marginalization.

The plight of Haitian migrants, fleeing U.S.-backed regimes, sweatshop labor, and economic violence, is a direct consequence of these bipartisan policies. The U.S. has consistently intervened in Haiti — through military occupation, support for dictators like the Duvaliers, and the enforcement of exploitative trade practices — while denying Haitians the right to seek refuge from the chaos it helped create.

The struggle for migrant rights and the liberation of Guantánamo Bay must be part of a larger fight against imperialism and capitalism which creates the conditions for the displacement of working class people. Only through building a sense of internationalism and struggling against U.S. imperialism can we give back stolen territories like Guantánamo and achieve justice and dignity for those whose lives have been greatly impacted by U.S foreign policy.