Glen Ford joined the U.S. army at age 17 and later reflected on the rise of the Black ghetto army here and in Vietnam.

The struggle for his life didn't dissuade Glen Ford from struggling with and for others.

Glen Ford and I never met in person because we lived on opposite coasts, but I had the honor of becoming a Contributing Editor at Black Agenda Report and we exchanged lots of email, most every day, for some years. I was usually sending news or thoughts of my own and asking for his insight, which he most generously shared.

In one of our last exchanges, I said, “I'm going to be up all night working on the Pacifica Radio hour that’ll be about the Horn of Africa this week. But I thought it might be encouraging if I sent this note to remind you of how much the people of the Horn appreciate BAR coming to their defense as the Power/Rice/Blinken/Biden gang bear down on them.”

He responded, “I’m so pleased that you are on top of these developments. Due to my illness, I haven't even responded to my Eritrean government friends who have reached out to us lately. I've got surgery in half an hour.”

After that I shared former US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Tibor Nagy’s surprising statement, made last November 2020, after the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front had attacked an Ethiopian Army base and then attacked neighboring Eritrea: “As I mentioned, we expressed our thanks to Eritrea for not being provoked when they were attacked by missiles because apparently, one of the aims of the TPLF hardcore leadership was to try to internationalize the conflict."

Glen responded:

“Interesting concession from a U.S. Under Secretary."

“My medical procedures today failed to unblock my lungs, by physical manipulation or radiation.”

I was hoping there’d be one more procedure to try, but two days later he was gone, just a week after publishing his last edition of Black Agenda Report. The Black Alliance for Peace announced that he’d passed from elder to ancestor.

Glen’s daughter Tonya had invited me to record and send a farewell message some hours before. Tough as that was I was glad for the chance and, in my message, I included the words of Ché Guevara: “At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.” Then I said the obvious, that he was a genuine revolutionary.

I’m listening right now to his brilliant speech at the Eritrean Festival in Oakland in 2012.

Glen had a wicked sense of irony

Knowing Glen, I regretted that I hadn’t managed to come up with a few good jokes in that farewell message, but I wasn’t up to it and didn’t know how much time I had, so I just did what I could. His readers no doubt knew what a wicked sense of irony he had but probably don’t know that he could even turn it to his own illness.

I called once when he was struggling and asked how he was doing, which seemed like an inane question by that time, but he responded, “I CAN’T BREATHE,” echoing the words of George Floyd and so many others with comic irony.

Glen suffered from kidney failure several years before developing lung cancer and had to begin a dialysis regime three days a week. Once we exchanged a few messages when he was on his way to a VA Hospital somewhere in Pennsylvania to be evaluated for a possible kidney transplant. On the way back he joked that due to his age—near 70 then— they couldn’t place him high on the waiting list and wouldn’t waste the best kidney available on him even if his number came up.

I told him that I’d never signed the release to donate my kidneys or any other organs because I’d subjected my body to so many toxins that my organs couldn’t be of much use to anyone. He said that had always been his excuse as well.

Once I sent him a piece about the latest violent incidents in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Virunga National Park, a wildlife reserve and jungle habitat in the heart of war-torn eastern Congo, and its valiant park rangers, many of whom have died defending it. Then I asked him which of several photos he’d like to use and he said, “I like the sister ranger. Took me back to what I used to get up to in my army days.” (The sister ranger was cute as hell in a beret and a perky ponytail.) We wound up using a pic of some brother park rangers with the mountain gorillas that the park is famous for, but I sent more pics later and said, “Here are some more of those sister rangers, since you like them so much.”

In 2018, he wrote a more serious account of his time in the U.S. Army and how his unit, the 82nd Airborne, was transformed by the Newark, New Jersey, race rebellion of 1967, a year before MLK was assassinated and they were deployed to Washington, DC:

“An 18 year-old paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne Division, stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, I had been on field exercises with my unit the week before, providing security for the commanding general’s headquarters. Under a big tent, company commanders and their executive officers spent that Wednesday, April 3, pouring over maps of Washington, DC, in the event we had to occupy the city. When King was killed on the evening of the next day, the division hastily packed its gear and moved back to barracks to prepare for deployment to burning cities. The general, however, somehow forgot to restrict all 12,000 of us to base. Some of us took advantage of the oversight, and went home for the weekend.

“When I and hundreds of other paratroopers straggled back to Fort Bragg early Monday morning, April 8, the rest of my unit was sitting on an airfield near Baltimore, as the brass tried to decide whether we should be deployed in that city or nearby Washington. Both were burning, along with over 100 other cities. We wound up in the nation’s capital.

“The year before, Newark, New Jersey, had been occupied by nearly lily-white units of the National Guard, sent there to quell a four-day rebellion in which 26 Blacks were killed. The Guardsmen behaved like an Army of White Vengeance, joining the racist cops in savaging Black people and shooting up businesses displaying “Black-owned” and “Soul Brother” signs on the Springfield Avenue thoroughfare. However, the 82nd Airborne Division was a different social organism, entirely; our ranks were 60 percent Black, and we had been transformed. All of us (at least in my company) were aware of what had happened in Newark. As far as the Black troops were concerned, our division had only one mission in Washington, DC: to make sure the white soldiers -- especially the mostly white military police -- did no harm to the Black population. And they did not dare. Not one Black citizen of Washington was hurt by a soldier of the 82nd Airborne division -- or, to my knowledge, even verbally abused -- during the occupation.

“Our officers took note, and were clearly disturbed by our protective postures. The same Black ghetto army that was rebelling in Vietnam, was showing that it would not be a party to abuse of Black people at home. It was the beginning of the end of the draft.”

It took me awhile to find that piece, MLK: A Snapshot in Time, dated April 5, 2018, in the Black Agenda Report archives, but I finally did after trying the search term “82nd Airborne.” I forget a lot of names, phone numbers and the like that I should retain, so my memory of that obscure detail speaks to how deeply the piece affected me. And to how much more accessible we need to make the BAR archives.

Shortly after Glen’s death, I told Margaret Kimberley, Ajamu Baraka, Raymond Nat Turner, and Danny Haiphong that people were no doubt reading and searching for their favorites in Glen’s BAR archives, as I just did, but that the archives are not as searchable as they should be. While Glen struggled with illness during the last few years of his life, he got the weekly edition of BAR out week after week, even that week before his death, but couldn’t find time or energy for projects like this, so we will. If anyone reading this has technical skills they might lend, please write to me at ann@anngarrison.com because I take particular interest in improving the Black Agenda Report’s accessibility and visibility on the Web.

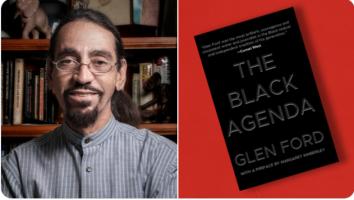

I’ve no doubt there will be a “Best of Glen Ford” volume in the works sometime soon, and that people will read it for many years to come.

Thank you, Glen Ford

Thank you, Glen, for your analytical and verbal brilliance, your tireless dedication, and your wicked sense of irony. Thank you for encouraging my work, especially my efforts to deconstruct all the racist, imperialist lies we’re told about African conflict and the US in Africa.

Thank you for helping so many of us stay sane despite the racist, right-wing, Neoliberalism that has been gaining force ever since the liberation movements of the 1960s and 70s were crushed. Thank you for letting us know that we’re not alone, that we’re not going out of our minds, and that the struggle is still worth engaging.

Glen usually began his talks and keynote addresses with, “Greetings! Power to the People!” All the love he said that with remains with us, and it’s our job to carry it forward.

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for promoting peace through her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes Region. She can be reached on Twitter @AnnGarrison and at ann(at)anngarrison(dot)com.