“The book calls for a liberation rooted in Black radicalism, but applicable to everyone made unfree by racial capitalism.”

The current political moment is dire. White supremacy has been given national sanction by the President of the United States, as white supremacists march with lit torches in Charlottesville, Virginia; as Klansmen feel newly justified; as alt-right fascists rear their heads at U.S. institutions of higher education. It appears that the President’s “Make America Great Again” slogan is a call for white supremacy. But it is not just the President’s speech nor the newfound publicity of alt-right nonsense that is most disconcerting; this administration is rolling back civil rights gains in voting, civil and LGBTQ rights; gutting environmental protections that impact the poor and people of color; scaling back social welfare programs like Medicaid; easing restrictions on policing; funneling resources into private prisons; and reinstituting some of the most heinous legacies of the War on Drugs. At the same time, the Trump Justice Department is targeting Black protest by labeling BLM protestors as, “Black identity extremists,” subject to counterterrorist policing. This administration’s invocation of white supremacy has a history -- indeed, Trump is merely calling for the nation to return to its white settler nationalist roots – but what strikes us as particular to this political moment is the ferocity of white supremacy following the first Black President of the United States, at a time when Black protest has emerged with new sophistication across the nation.

“Trump is calling for the nation to return to its white settler nationalist roots.”

It would be tempting to view this moment only as one characterized by an ascendant white supremacy and anti-Blackness, given new strength and legitimacy by the executive branch of the U.S. government. But to view the current moment only in this way is to ignore how the seeming strength and vitality of white supremacy and toxic masculinity may in fact be indications of their fragility and tenuousness. Indeed, while the forces of white supremacy have waited a long time for a President like Donald J. Trump, the new-found legitimacy of white supremacist organizations may be rooted in its long-time fragility, decline, and weakness.

It was one of the many major contributions of Dr. Cedric J. Robinson to understand the force of white supremacy as a forgery of history and memory, a “covering conceit” rooted in racial capitalism. For Robinson, there can be no understanding of capitalism without acknowledging its racial dimension. Race was the forgery deployed to partition the globe under colonialism, to partition populations so as to exploit labor, and to make way for accumulation. Avoiding the pitfalls some on the left currently find themselves in, between arguing for race against class, Robinson understood that race and class are inextricably bound; there has never been a capitalism that is not racial, hence Robinson referred to “racial capitalism.”

“Race was the forgery deployed to partition the globe under colonialism, to partition populations so as to exploit labor, and to make way for accumulation.”

Racial capitalism is an unstable formation, one that is continually requiring cultural and political work to shore up its insecurities. Hence, Robinson studied race as an ideological formation of capitalism that was constantly in crisis and in need of redefinition. This explains why he saw the most vociferous moments of racial supremacy not merely as dangerous examples of dominant power, but also as moments that exposed the fragility of power and its continual need to be shored up through “forgeries of memory and meaning.”

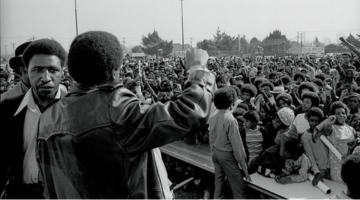

Moreover, Robinson understood that the dream of liberation on the part of Black radical artists, thinkers, and activists took place independently from racial capitalism; hence, Robinson studied what he called the Black Radical Tradition as the accumulated wisdom of freedom strivers, ancestors, and Black radical thinkers. And in this way, Robinson identified a radical tradition constantly expressing itself in everyday life and not just in the sanctioned domains of politics and governance. This is why Robinson delighted in writing about film and culture as well as in social movement; each example could be conceived as drawing from the well of the Black radical tradition.

“There has never been a capitalism that is not racial.”

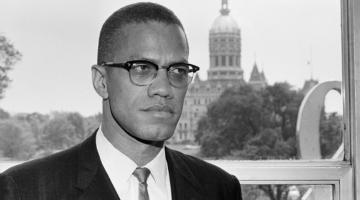

Robinson was most interested in a form of Black radical thinking rooted in acts of political refusal, exile, and escape. As he and Elizabeth Robinson articulate in the preface to Futures of Black Radicalism, Robinson was interested in the politics of maronage, a politics of everyday Black radical thinkers who refused, as H.L.T. Quan writes in the book, to be governed. Hence, Robinson focused on former Black captives who removed themselves to the Great Dismal Swamp traversing Virginia and North Carolina, where they reconstituted the world outside of a modernity that denied their humanity. According to Robinson, the political theory that emerged from places like the Great Dismal Swamp could not be adequately named “Marxism,” although Marxism may have been a useful lens through which to understand and plot Black radicalism. Robinson sought to identify an organically Black radical political philosophy that he coined “Black Marxism,” a radical anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist Black philosophy rooted in the understanding of racial capitalism and originating before the invention of Europe.

Robinson’s insights about Black radicalism led him to explore the origins of the Black radical tradition outside of Europe and before the ascendance of the European working class. He looked to pre-capitalist societies in Africa and the Mediterranean world, where Black resistance would be formed and transferred through generations. Because he looked beyond Europe to understand “Black Marxism,” Robinson’s scholarship was worldly and world-making in ways rarely duplicated in the Western academy.

“Robinson identified a radical tradition constantly expressing itself in everyday life.”

Futures of Black Radicalism is a collection of essays commissioned by Cedric and Elizabeth Robinson. The book is organized to reflect the arc of Robinson’s interventions, including an understanding of racial capitalism, an understanding of the Black Radical tradition, and an understanding of what sort of future politics are called for given Robinson’s framework. Ultimately, the book is a call for a Black radical politics in the Robinson tradition; one that is internationalist, abolitionist, and intersectional. This is why the final section of the book looks to various political movements, from interventions in art, Black radical’s refusals to be governed, and abolitionist politics. In the end, Futures of Black Radicalism calls for a liberation rooted in Black radicalism, but applicable to everyone made unfree by racial capitalism. As we indicate in our introduction to the book,

“In all of his writings on the Black Radical Tradition, Robinson revealed with great care the precision with which Black freedom fighters discerned the fractures in regimes of racism and state power. He archived their commensurate insurrections, seen and unseen, as evidence of an uncompromising struggle to end tyranny and oppression. The endurance of these practices has done more than bolster the courage of Afro-diasporic people: it has commissioned imaginaries and generated epistemologies that have shaped radical intellectual traditions across the world. It is our hope that this book will inspire a greater consciousness of the specific inheritances of the Black Radical Tradition. The futures of Black radicalism depend on it.”

Gaye Theresa Johnson is Associate Professor of Black and Chicana/o Studies at UCLA and author of Spaces of Conflict, Sounds of Solidarity: Music, Race, and Spatial Entitlement in Los Angeles.

Alex Lubin is Professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico. He is the author of Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary.