For Black August, read William L. Patterson on racial genocide, the law, and the Martinsville Seven.

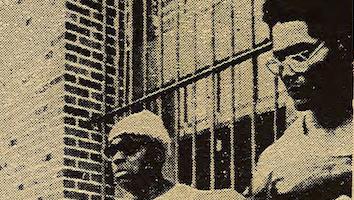

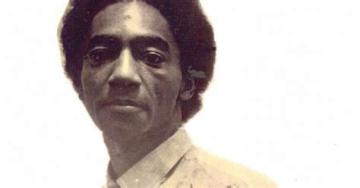

The political career of radical lawyer and Black communist William L. Patterson is marked not only by his dedication to raising awareness of the unjust and racist nature of the United States legal and penal systems – but also to liberating those swept up in the systems’ demonic machinery. Born in 1891 in San Francisco and raised between Oakland and Mill Valley, Patterson studied law, flunked the California bar, and, after a failed attempt to emigrate to Liberia, ended up in Harlem. Patterson eventually passed the New York Bar examination and became a successful Sugar Hill lawyer. But Patterson was radicalized through his conversations with Caribbean militant Richard B. Moore. It wasMoore who urged him to use his legal skills in support of Sacco and Vanzetti, Italian anarchists condemned to death in 1927 for their alleged involvement in a murder and robbery.

From 1927 on, Patterson’s agitation was unceasing. He quit his law firm, joined the Communist (Workers) Party, studied at the New York Worker’s School and the University of the Toiling People of the Far East in Moscow, before returning to the US were he headed the International Labor Defense (ILD). The ILD led the successful campaign in the early 1930s to stop the execution of the Scottsboro “boys,” eight African Americans facing the death penalty for allegedly raping two white women in Alabama. In 1951, Patterson and Paul Robeson spearheaded the efforts to petition the United Nations charging the United States with the genocide of African Americans. A decade later he would provide legal counsel to Angela Davis and the Black Panther Party.

In Patterson’s pedition to the United Nations – published as We Charge Genocide – he and his co-petitioners presented as evidence a cruel archive of cases where Black people had been incarcerated or executed by the state after their appeals to the US Supreme Court were ignored. They documented cases of Black prisoners who were shot when they refused to work, of a Black farmer murdered for sport by a white game warden, of “the Trenton Six, of Paul Washington, the Daniels cousins, Jerry Newsom, Wesley Robert Wells, of Rosalee Ingram, of John Derrick, of Lieutenant Gilbert, of the Columbia, Tennessee destruction, the Freeport slaughter, the Monroe killings—all important cases in which Negroes have been framed on capital charges or have actually been killed.” Among their evidence was that of the Martinsville Seven – seven Black men “who died in Virginia’s electric chair for a rape they never committed, in a state that has never executed a white man for that offense.”

In 1969, almost two decades following the execution of the Martinsville Seven, Patterson revisited the case in a short essay for San Francisco Black newspaper, the Sun-Reporter. Patterson’s essay, reprinted below, reminds us that today, Black genocide still occurs “under color of law.” It makes for critical Black August reading.

Racial Genocide: The Case of the Martinsville Seven

William L. Patterson

It happened in Richmond, Virginia, 18 years ago [1951]. Seven young black Americans went to a premature death in the State's electric chair. It was all done "legally." A white woman crazed from the myths of white superiority, bereft of all sense of honor or respect for human dignity, cried . . .. A trial court of racists heard the case and passed the death sentence. The all-white Virginia Supreme Court listened to the appeal but refused to grant a new trial. The United States Supreme Court could not find in the conspiracy to murder seven black men a violation of their constitutional rights. It was legally carried out -- this genocide under color of law.

Caborn Taylor, Frank Hairston Jr., Joe Henry Hempton, James Hairston, Booker F. Miller, Francis Grayson and J. L. Hairston had been sentenced to death for the alleged mass raping of a white woman. According to the evidence, they could not have been guilty.

The Martinsville Seven were thrust into the electric chair. But the case had many lessons. It revealed the murderous course of racism when that crime is made a policy of government. It exposed the complicity of the Supreme Court in the victimization of literally tens of thousands of innocent black Americans. It offered proof that to save our country, racism must be ended.

The Martinsville Seven were not just seven innocent men. They were the symbol of a system of government rotten unto death with the curse of racism. Yet, it will not die of itself.

Now it is part of the history of our country. That is why we return to commemorate this murder. It is not part of the mythology of American history that proclaims all men to have been created equal and proceeds to glorify all that is white and impeach all that is black. This genocidal vent is part of the story of the first three centuries of slavery and inhuman racist terror and part of the history of the century after the Civil War. Historians with few exceptions have ignored the decisive role of black men and women played in this war drama. They have concealed the magnificent contributions of black men to the growth and development of our country since then, and through the press, in school and church, they have sought to create an image of the black man as a rapist and a buffon.

Those who rule, our ruling class and power elite, have made this false imagery a major ideological weapon. The purpose: that we should be a nation divided along the color line and unable as one people to recognize the main enemy -- our monopolists -- and meet together the problems of poverty, miseducation, unjust and unequal taxation, deteriorating cities, joblessness and insecurity it has produced, to say nothing of its wars of aggression.

The murder of the Martinsville Seven was an act of racist terror. As was the Scottsboro case before it, it was calculated not only to terrorize a people and quell their militancy and deathless courage, but more particularly to create a massive white backlash and hide from white slum dwellers and labor the mutuality of interests of whites and blacks in this society.

But terror cannot materially strengthen a government steeped in the degenerating myths of a superiority based on color.

Josephine Grayson, wife of Francis Grayson, one of the victims of this colossal racist conspiracy, and mother of five children, brought the arrest of these men in Martinsville, Va., to the attention of the Civil Rights Congress (CRC). I went at once to Richmond. The accused had been carried there and I wanted to talk with them.

The tasks of the CRC were clearly defined: to create a united front of organization for the defense; to free these innocent men and in the process to place details of the case before the peoples of the world, mobilizing protest sentiment in every. possible country against this terrorization; to expose the hollowness of the doctrine of States' Rights and the role of U.S. Government in the persecution of black nationals; to reveal the social forces that it served in this capacity and to prove that the courts would not move from the racist position of the class for which they conducted business unless the mass rejection of their sentences moved hundreds and hundreds of thousands into protest action.

The matter of struggle was discussed with the leadership of the Virginia State NAACP. Joint action was agreed upon but the National Office repudiated that agreement and the CRC went on alone.

In the history of Virginia no white man had ever been executed for the crime with which these men were charged. The men had been playing games when the woman approached. As the evidence goes, she solicited them. She was a prostitute. She declared that all of them raped her.

It is not hard to analyze the interrelationship between virulent racism and crisis in our country. Racism is a constant companion of crisis. The frame-up of the Martinsville Seven came at a moment of deepening and sharpening struggle on the part of America's black and oppressed millions.

I visited the men in the death house of the State Penitentiary. There were thirteen men in the house of doom. Nine of them were black. I inquired as to the composition of the prison population. The warden said that more than 65 per cent were black. This in a state where the black population approximated 20 per cent. Thus was the image of black criminality built up.

The murder of the Martinsville Seven poses in perpetuity a question the white masses -- and especially labor in a white skin -- must answer. Racism is not the property of white America. It is a weapon of its ruling class. It serves to divide, to separate, to pit those who should by virtue of social conditions be natural allies against each other. What are the white masses of America, what is labor going to do about it? Labor needs an anti-race program that will draw millions of black men into its ranks. It needs a program consistent with the political and economic demands from the ghetto. It needs unity with the black community.

William L. Patterson, “Racial Genocide: The Case of the Martinsville Seven,” Sun Reporter, (15 February 1969).

For more on Patterson see Gerald Horne’s Black Revolutionary: William L. Patterson and the Globalization of the Black Freedom Sruggle and Patterson’s The Man Who Cried Genocide: An Autobiography.

Image: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "William L. Patterson, executive director of the Civil Rights Congress, addressing the Bill of Rights Conference, circa 1940s." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1940 - 1949.