“When the American and West Indian Negroes get to know their history…they will have a greater love for the African through whom they have sprung.”

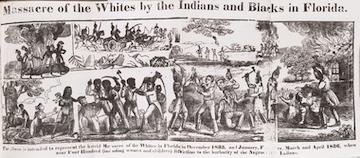

On August 1, 1834, slavery was officially abolished in the British colonies. The Slavery Abolition Act, given royal assent the previous year, legally released from bondage some 800,000 enslaved Africans dispersed across England’s colonies in the Caribbean, South Africa, and Canada. Yet for these Africans, abolition did not mean emancipation. The Abolition Act instituted a ten-year period of “apprenticeship” for the formerly enslaved that kept them tethered to the plantation, working under conditions little different than slavery. Meanwhile, in 1837, the British government authorized the payment of £20 million — the equivalent of £16 billion today — to the slave owners for the loss of their human property. The Africans, as Marcus Garvey observed, “were set loose upon the world without a cent in their pockets or a bit of land to settle on that could be called their own.”

The 1934 centenary of abolition offered Garvey an opportunity to muse on the apparently diverging fates of formerly enslaved Africans in the Caribbean, and in the United States. In an editorial in The Blackman, Garvey observed that it was common to offer a negative comparison of the two populations, to suggest that, because of population and racial prejudice, one was somehow better off than the other. Yet for Garvey, such a comparison was a specious one, missing the common “kinship” of West Indians and African Americans. Decades after emancipation, both populations “were almost where they were when they came off the plantations,” and both populations, no matter what country they ended up in, shared a common origin in Africa. For Garvey, recognizing these commonalities was a requirement for Black liberation.

Yet today, common kinship of Africans throughout the world has been poisoned by a toxic nationalism that only serves to strengthen and maintain white rule and many of us “are still drifting with the white man’s civilization.” As we celebrate another Emancipation Day in the former British colonies and slouch towards the bicentenary of abolition, many African people have forgotten Garvey’s words. We reprint them below.

Centenary of Negro Emancipation

Marcus Garvey

August of this year will mark the first Centenary of the Emancipation of the Negroes of the British West Indies, in that in the year 1833 the British Parliament passed the Emancipation Act which came into effect the following year, 1834, at which time a few of the West Indian slaves got their freedom; but it was not until 1838 that the wholesale Emancipation of West Indian Negroes took place. Because the first West Indian Negroes were freed in 1834 it is considered that this is the proper year to celebrate the Centenary of Emancipation. The West Indian Negroes, to a certain extent, have accomplished much in the one hundred years. They, like the American Negroes who were freed in 1865, through the good efforts of Abraham Lincoln, were set loose upon the world without a cent in their pockets or a bit of land to settle on that could be called their own. From the beginning they have had to fight their way up to where they are today. Some have done well, and the great majority are almost where they were when they came off the plantations. They are propertyless and almost helpless.

The tens of thousands of Negroes in the different islands at that time who got their freedom, have now multiplied in some islands to hundreds of thousands and in the island of Jamaica to nearly a million. The millions of Negroes of the West Indies, like the millions of Negroes of the United States, have not yet formulated a programme of racial preservation nor have they any settled racial outlook. They are still drifting with the white man’s civilization.

As we have pointed out elsewhere, the organized prejudices against the American Negro have somewhat inspired in him some kind of racial consciousness. That is due to the fact that he is a minority in the county of his adoption, while in the West Indies the Negroes are in the majority; and so, it would not be good policy to encourage racial antagonism: therefore, the West Indian Negroes have grown up without racial consciousness. This has contributed much to his weakness and his inability to accomplish much by himself. Some think that he is much better off than the American Negro because of the absence of organized prejudice in his midst, whilst the thoughtful think that the American Negro is far better off than the West Indian Negro, because of the prejudice practised against him, he has developed an independence in the different walks of life that may lead ultimately to his economic salvation. The two branches of liberated Negroes have grown up separate and apart without any recognition of their kinship.

During the Slave Trade, Negroes were often shunted from the West Indies to the Colonies in the America, and most of the American Negroes to-day can trace their origin back to Negroes who were shipped from Africa via the West Indies and to a large number of those who actually were sold from the West Indian Islands to slave-holders in the Southern sections of the United States, then the Thirteen Colonies. When the American and West Indian Negroes get to know their history, there will naturally spring up among them a better feeling of sympathy and comradeship, and when both of them become more conscious of their own origin they will have a greater love for the African, through whom they have sprung. It seems very sad that these three units of the Negro race should have lived so long without the conscious knowledge of their true relationship. It is hoped, however that the Universal Negro Improvement Association will do much to cement them together in one bond of racial pride that will enable them to extricate themselves from the difficulties that now surround them in the countries of their dispersion.

The celebration of the Centenary will take place this year, and it is hoped that the Negroes will have much to show by way of improvements upon their conditions of one hundred years ago.

Marcus Garvey, “Centenary of Negro Emancipation,” The Blackman: A Monthly Magazine of Negro Thought and Opinion 1 no. 5 (May-June, 1934).