The brutal physical assault against Théodore Luhaka by three police officers, and their subsequent acquittal, is a heartbreaking example of the long relationship between the colonizer and the colonized - one that denies their humanity and claims ownership over their bodies.

Originally published in Frantz Fanon Foundation

For ten days – from January 9 to 19, 2024 – the trial of the three police officers who mutilated Théodore Luhaka, aged 22 at the time, was held. Seven years of waiting, seven years of medical operations, seven years of expert assessments, seven years of suffering that still hasn’t stopped, seven years for Théo during which his life has been turned upside down, changed and is nothing like it was when he was 22.

Ten days of trial for seven years of waiting; he repeats that his body died on February 2, 2017, that he died; the date on which his life came to a halt, so severe and disabling are the after-effects of this mutilation. Ten days in which it was possible to see an aggressive defense, attempting to delegitimize the facts in order to shift the blame onto the victim; ten days in which the racist insults, including « baboon », and the use of familiar language were denied, while Théo, a young black man from the suburbs, constantly confirmed them; what was instilled in the jurors’ heads, since the videos were devoid of sound, is great perfidy: no proof of the insults uttered, so the victim is a liar; ten days in which the justice of class and race has put in place, despite the start of the public prosecutor’s unappealable indictment, the cross-examinations of the prosecution and Théo Luhaka’s testimony, a strategy to delegitimize the victim in order to build up an image of conscientious police officers with impeccable reputations, despite the fact that two of them had already been summoned a week before the events, following a complaint from a victim who had been arrested with extreme violence. They were acquitted.

What had to be understood was that, even if the crime had been proven, the elements – or more precisely, their analysis and interpretation – had to enable the jurors to transform the crime into a misdemeanor, so that the defendants could escape a prison sentence.

As the days went by, it was easy to see a strategy being put in place to change the characterization by blaming the victim for what he had done or said, and the media played a deleterious role in this. The machine was set in motion and worked; the criminals were, in a way, absolved; the victim accepted the verdict, the acts of deliberate aggravating violence resulting in incapacity were recognized. For Théo, the truth has been told, and this will certainly act as a catharsis. Yet justice has not been done. These police officers betrayed the law and the ethics of their profession, and at least two of them were expected to be sentenced to prison for having mutilated this young man for life, for having committed a facial profiling offence in a popular housing estate, for having used excessive force that was neither justified nor proportional, and for having subjected him to degrading and humiliating treatment, and breaches of the Internal Security Code, as indicated by the French Human Rights Ombudsman, who in 2020 recommended that « disciplinary proceedings » be taken against them.

In a way, it was a question of providing elements for an indictment in favor of the police officers, so that they would emerge ‘cleared’ of the crime committed. The public prosecutor’s indictment came as a surprise to many: he was uncompromising in his criticism of the three police officers, accusing them of ambiguities and inaccuracies in the drafting of the arrest report, with certain facts missing from their statement to the IGPN, and even of forgery in public writings; did he not note « distortions between the report and the complaint » of the main accused? And yet, the demands contained in the indictment did not reflect the need for justice for Théo : a three-year suspended sentence for the main defendant, and a five-year ban from the street work and carrying weapons; a six-month suspended sentence for the second defendant, a two-year ban from the street work and carrying weapons; a three-month suspended sentence for the third defendant. The door had been opened: jurors could now rule on a misdemeanor rather than a felony. Impunity is all too often, if not systematically, accepted when the perpetrators of police violence are public security agents. How many times have we heard that our society needs the police? How many times have we heard that the police are a difficult but necessary profession?

From the very first days, the most convincing aspect was that both the defense and the presiding judge were tempted to portray Théo, a young man with no history of violence, who had never had any run-in with any repressive institution and who had, for a time, been a mediator with the youth of the cité, as a violent, even rebellious person; as if this should be so in view of his physical build, tall, 1. 85m, muscular and athletic, weighing some 95 kilos at the time, and a final argument in support of a biased representation of Théo: at the time of the events, hadn’t he been training to be a professional footballer? He was therefore over-trained, as one of the police officers tried to prove, pointing out that he was « always on the move and always moving forward »; even after being tear-gassed in the eyes, « he continues to move, why? », « he’s a violent, aggressive individual ». He considers Théo to be over-trained, whereas this is far from being the case for them: « We’re not over-trained, we don’t always have the time ». How in the police officers’ heads was the connection built: black, living in the 3,000 housing estate since birth, athletic with delinquency and drug dealing?

On February 2, 2017, the police officers -four in number-, having decided, on their own initiative, to carry out an identity check, even though there was no justification for it under article 78-2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, they came into contact with a group of young people standing « at a well-known dealing point » – even though this point was not on the slab near the CAP – the cultural center in Aulnay sous Bois – but in the basement, in the parking lot, as confirmed by the CAP janitor, now retired. At the same time, At the same time, Théo passes through the area to meet a friend of one of his sisters, greets the young people, the police officers announce the check; the tone rises, a young person refuses to be checked; the police officers take him away off the surveillance camera, one of the officers slaps him. Théo steps in to defuse the tension, asking the policeman why the identity check was necessary, even though the three of them know most of the youngsters. At this point, the police violence begins and everything is going crazy.

The defendants arrogantly asserted that Théo Luhaka refused to be checked, as he would not have his identity card with him. The result is indisputable: not only was Théo mutilated with a telescopic defense baton -BTD-, causing more than 10 centimeters of anal tearing, but he also filed a complaint for resisting the Specialized Field Brigade -BST- and unintentionally hitting one of the police officers: violence against a person in a position of public authority, even though it is clearly established from the videos that the latter did not strike anyone voluntarily on the other hand, the stab wound that mutilated him for life, was indeed delivered by one of the police officers; many other blows followed. In the verdict, the three police officers were charged with intentional violence, committed as part of a group, with aggravating circumstances including the use of a weapon in the case of the main defendant, which resulted in permanent disability, and the use of a weapon known as « la gazeuse » – an anti-aggression spray – in the case of the second. In all three cases, there was no mitigation of responsibility, in simple terms, for self-defence.

Throughout the two-week trial before the Bobigny assize court, the three defendants constantly essentialized the young people from the 3,000 cité in Aulnay sous-Bois, asserting that most of them are drug dealers, or at least have a link with drug trafficking, since they are found on the CAP slab. One of them points out that « if someone is seen several times on a drug site, then we know they’re involved in trafficking ». Any young person is bound to be a delinquent! « As for another, the man who used his « gazeuse » three times in the direction of Théo’s face, he explained that he believed « at the time that he was a dealer », « he’s a determined person, I suspect he hit my colleague, he wants to escape control », adding that he « represents a danger, his leg is twitching, he wants to leave ». None of them knew Theo or had seen him before February 2, 2017.

The same policeman explained that when he tried to handcuff Théo, he was faced with « a trench battle ». For him, the 3,000 cité is « a rotten housing estate, I’m fed up with these bastards ». He admits that the direct punch to the face of Théo, who was handcuffed at the time, was « a gesture of anger, the arrest slipped out of my hands ». It slipped out of the hands of each of the police officers who appeared before the court.

A number of questions remain unanswered during this trial, and any reflection on police violence requires us to address them. They concern, on the one hand, the act of mutilation itself: this young man has suffered a symbolic rape of his most ‘intimate’ intimacy; and on the other hand, the reason why these three police officers, in the space of an unjustified stop, materialized the domination of the white settler over Théo’s black body. What did Théo’s resistance to an unwarranted stop awaken in their minds? What unconscious, common to their group, was released to use unjustified voluntary violence?

It was as if they were trying to confirm their position of dominance as « guardians » of public safety, and that they could get the upper hand over a body that should not normally resist their uniform and BTD. All the young people from the 3,000 housing estate in Aulnay sous-Bois or Sevran know what Théo went through; they expressed their dismay and, above all, their total loss of confidence in an apparatus that wants to control them and treat them as by-products of humanity.

The aim is to make them bend over, to put them on their knees so that they understand that in their hands – they who represent ‘law and order’- they are just objects and that they can do what they like with them. To rob them of their dignity by putting them in degrading and humiliating postures – like the 151 young people in the Mantois area, held on their knees with their hands on their heads for hours after a high school demonstration – or by seriously injuring, mutilating or killing them.

The police officers committing these acts feel protected not only by their uniforms and weapons, but also by their hierarchy and the entire apparatus put in place to protect the system of capitalist and racist domination, including the justice system, which has never handed down a firm sentence to criminal police officers, or which prefers to dismiss cases rather than apply the law, which would have been more than applied if the same act had been carried out by a black or Arab body.

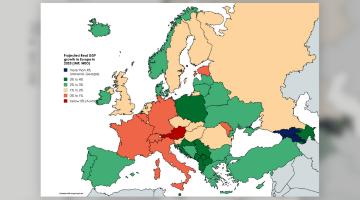

These paradoxes, which can be analyzed at the French level, are also true in other countries, but also at the regional and even international level. This two- or three-speed justice system, or even more, is hardly surprising, and the racist, class-based justice system unfortunately appears to be the norm in a system where the coloniality of power determines the lives of Beings and, above all, Non-Beings.

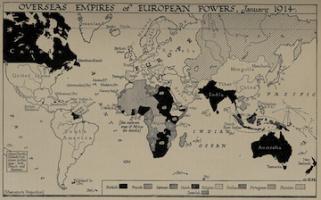

With this system, the body, whether black or Arab, precarious and poor, must be treated as an object, objectified by the white gaze, a posture endorsed by successive governments. We seem to be eternally replaying the overhanging relationship that the colonizer imposed on the enslaved and the colonized: preventing these bodies from ensuring and assuming their humanity by preventing them from claiming their dignity. The coloniality of power conferred on police officers by their status as agents of public authority blinds them and makes them lose all discernment: they operate in an overgeneralization that all young people from working-class neighbourhoods and peripheral areas are thieves, rapists and traffickers. Is this not how, during the colonial and colonizing period, black bodies were feared or hated, judged and lynched for their alleged « hyper-sexuality »?

The masters had the right of life and death over the bodies of the enslaved, with no moral objections. It was necessary to provide the nascent capitalist system with a free labor force from which to profit, while depriving them of their humanity and dignity through extreme violence. Times have changed: the capitalist system treats the colonized from within as supernumerary bodies; and if it needs a workforce, it calls on those who have become the new slaves of the liberal capitalist system: migrants.

With its usual perfidy, the system groups together all those it considers to be non-beings in a peripheral urban space, more akin to a ghetto than a welcoming city, and contains them in places where everything is done to ensure that only survival is possible. To escape is the exception. To keep young people in the city, the drug trade is encouraged, with its dealers, spotters and customers adventuring into areas that must seem more than exotic to them.

In the wake of what some are calling the « Théo affair », our society is going to have to question the expression of its negrophobia towards young people on the periphery, and its institutional violence, of which black and Arab bodies are the majority victims, unless it is contemplating its own death for having killed and mutilated its citizens. To help it analyze its own racist and Islamophobic failings, the work carried out by the victims’ families is fundamental. Not only they demand justice, a judgement proportional to the extreme seriousness of the act committed against one of their own, but they refuse to give up in the face of the difficulties they have to go through. They mobilize, are present at all hearings, inform and yield nothing even if they object to a dismissal; they look for the slightest flaw, carry out counter-investigations, take on their own detectives; they concede nothing.

Standing up for the dignity snatched from their loved ones. Determined, in solidarity. They are leading an exemplary struggle to enable the black, Arab and racialized body to regain its dignity, stolen since 1492 by those who decided the chaotic and deadly course of the world. An approach that questions the paradigm of domination, in order to impose the need for political and collective reparations after the human catastrophe of the discoveries and colonization of inhabited lands, resulting in the genocide of indigenous peoples and the enslavement of millions of Africans torn from their continent. A fight for human dignity!

Mireille Fanon Mendes-France is founder and co-chair of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. She served as former United Nations expert chair of the Working group on People of African Descent. Mireille works on issues of International law and has worked as professor at different levels of the National Education, at Unesco and as legal adviser at French National Assembly. Mireille Fanon Mendès-France is the daughter of the world-renowned revolutionary, psychiatrist and political author, Frantz Fanon.