For eight months in 2011, the U.S. and its NATO allies waged aggressive war against the sovereign state of Libya, to the cheers of much of what passes for the Left in the imperialist countries. Maximilian C. Forte’s book “presents a multi-factorial account, which invokes elements of the hunt for profits, economic competition with China and Russia, and establishing US hegemony in Africa.”

Maximilian C. Forte, Slouching Towards Sirte: NATO’s War on Libya and Africa, Baraka Books, Montreal, ISBN 978-1-926824-52-9. Available November 20, 2012. http://www.barakabooks.com/

This review previously appeared in Marxism-Leninism Today.

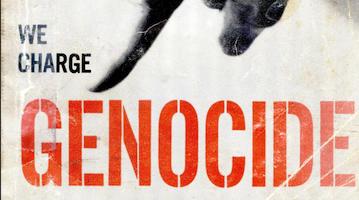

“A massacre was never in the cards, much less genocide.”

The next time that empire comes calling in the name of human rights, please be found standing idly by.

Maximilian C. Forte’s new book Slouching Towards Sirte: NATO’s War on Libya and Africa (released November 20) is a searing indictment of NATO’s 2011 military intervention in Libya, and of the North American and European left that supported it.

He argues that NATO powers, with the help of the Western left who “played a supporting role by making substantial room for the dominant U.S. narrative and its military policies,” marshaled support for their intervention by creating a fiction that Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was about to carry out a massacre against a popular, pro-democracy uprising, and that the world could not stand idly by and watch a genocide unfold.

Forte takes this view apart, showing that a massacre was never in the cards, much less genocide. Gaddafi didn’t threaten to hunt down civilians, only those who had taken up armed insurrection—and he offered rebels amnesty if they laid down their arms. What’s more, Gaddafi didn’t have the military firepower to lay siege to Benghazi (site of the initial uprising) and hunt down civilians from house to house. Nor did his forces carry out massacres in the towns they recaptured…something that cannot be said for the rebels.

Citing mainstream media reports that CIA and British SAS operatives were already on the ground “either before or at the very same time as (British prime minister David) Cameron and (then French president Nicolas) Sarkozy began to call for military intervention in Libya”, Forte raises “the possibility that Western powers were at least waiting for the first opportunity to intervene in Libya to commit regime change under the cover of a local uprising.” And he adds, they were doing so “without any hesitation to ponder what if any real threats to civilians might have been.”

“Countries that want to maintain some measure of independence from Washington are well advised not to surrender the threat of self-defense.”

Gaddafi, a fierce opponent of fundamentalist Wahhabist/Salafist Islam “faced several armed uprisings and coup attempts before— and in the West there was no public clamor for his head when he crushed them.” (The same, too, can be said of the numerous uprisings and assassination attempts carried out by the Syrian Muslim Brothers against the Assads, all of which were crushed without raising much of an outcry in the West, until now.)

Rejecting a single factor explanation that NATO intervened to secure access to Libyan oil, Forte presents a multi-factorial account, which invokes elements of the hunt for profits, economic competition with China and Russia, and establishing US hegemony in Africa. Among the gains of the intervention, writes Forte, were:

1) increased access for U.S. corporations to massive Libyan expenditures on infrastructure development (and now reconstruction), from which U.S. corporations had frequently been locked out when Gaddafi was in power; 2) warding off any increased acquisition of Libyan oil contracts by Chinese and Russian firms; 3) ensuring that a friendly regime was in place that was not influenced by ideas of “resource nationalism;” 4) increasing the presence of AFRICOM in African affairs, in an attempt to substitute for the African Union and to entirely displace the Libyan-led Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD); 5) expanding the U.S. hold on key geostrategic locations and resources; 6) promoting U.S. claims to be serious about freedom, democracy, and human rights, and of being on the side of the people of Africa, as a benign benefactor; 7) politically stabilizing the North African region in a way that locked out opponents of the U.S.; and, 8) drafting other nations to undertake the work of defending and advancing U.S. political and economic interests, under the guise of humanitarianism and protecting civilians.

“Libya led by Gaddafi (had) fought against Al Qaeda years before it became public enemy number one in the U.S.”

Forte challenges the view that Gaddafi was in bed with the West as a “strange view of romance.” It might be more aptly said, he counters, that the United States was in bed with Libya on the fight against Al Qaeda and Islamic terrorists, since “Libya led by Gaddafi (had) fought against Al Qaeda years before it became public enemy number one in the U.S.” Indeed, years “before Bin Laden became a household name in the West, Libya issued an arrest warrant for his capture.” Gaddafi was happy to enlist Washington’s help in crushing a persistent threat to his secular rule.

Moreover, the bed in which Libya and the United States found themselves was hardly a comfortable one. Gaddafi complained bitterly to US officials that the benefits he was promised for ending Libya’s WMD program and capitulating on the Lockerbie prosecution were not forthcoming. And the US State Department and US corporations, for their part, complained bitterly of Gaddafi’s “resource nationalism” and attempts to “Libyanize” the economy. One of the lessons the NATO intervention has taught is that countries that want to maintain some measure of independence from Washington are well advised not to surrender the threat of self-defense.

Forte, to use his own words, gives the devil his due, noting that:

"Gaddafi was a remarkable and unique exception among the whole range of modern Arab leaders, for being doggedly altruistic, for funding development programs in dozens of needy nations, for supporting national liberation struggles that had nothing to do with Islam or the Arab world, for pursuing an ideology that was original and not simply the product of received tradition or mimesis of exogenous sources, and for making Libya a presence on the world stage in a way that was completely out of proportion with its population size."

“The slaughter in Sirte barely raised an eyebrow among the kinds of Western audiences and opinion leaders who just a few months before clamored for ‘humanitarian intervention.’”

He points out as well that “Libya had reaped international isolation for the sake of supporting the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and the African National Congress (ANC)”, which, once each of these organizations had made their own separate peace, left Libya behind continuing to fight.

Forte invokes Sirte in the title of his book to expose the lie that NATO’s intervention was motivated by humanitarianism and saving lives. “Sirte, once promoted by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi as a possible capital of a future United States of Africa, and one of the strongest bases of support for the revolution he led, was found to be in near total ruin by visiting journalists who came after the end of the bombing campaign by members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

“This,” observes Forte, “is what ‘protecting civilians’ actually looks like, and it looks like crimes against humanity.” “The only lives the U.S. was interested in saving,” he argues “were those of the insurgents, saving them so they could defeat Gaddafi.” And yet “the slaughter in Sirte…barely raised an eyebrow among the kinds of Western audiences and opinion leaders who just a few months before clamored for ‘humanitarian intervention.’”

Among those who clamored for humanitarian intervention were members of the “North American and European left—reconditioned, accommodating, and fearful—(who) played a supporting role by making substantial room for the dominant U.S. narrative and its military policies.” Forte doesn’t name names, except for a reference to Noam Chomsky, whom he criticizes for “poor judgment and flawed analyses” for supporting “the no-fly zone intervention and the rebellion as ‘wonderful’ and ‘liberation’”.

“Massacres were not prevented, they were enabled, and many occurred after NATO intervened and because NATO intervened.”

Forte also aims a stinging rebuke at those who treated anti-imperialism as a bad word. “Throughout this debacle, anti-imperialism has been scourged as if it were a threat greater than the West’s global military domination, as if anti-imperialism had given us any of the horrors of war witnessed thus far this century. Anti-imperialism was treated in public debate in North America as the province of political lepers.” This calls to mind opprobrious leftist figures who discovered a fondness for the obloquy “mechanical anti-imperialists” which they hurtled with great gusto at anti-imperialist opponents of the NATO intervention.

“NATO’s intervention did not stop armed conflict in Libya,” observes Forte—it continues to the present. “Massacres were not prevented, they were enabled, and many occurred after NATO intervened and because NATO intervened.” It is for these reasons he urges readers to stand idly by the next time that empire comes calling in the name of human rights.

Slouching Towards Sirte is a penetrating critique, not only of the NATO intervention in Libya, but of the concept of humanitarian intervention and imperialism in our time. It is the definitive treatment of NATO’s war on Libya. It is difficult to imagine it will be surpassed.

Stephen Gowans is a writer and political activist who lives in Ottawa, Canada.