BAR Book Forum: William C. Anderson’s “The Nation on No Map”

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is William C. Anderson. Anderson is a writer and activist from Birmingham, Alabama. His work has appeared in the Guardian, MTV, Truthout, British Journal of Photography, and Pitchfork, among others. His book is The Nation on No Map: Black Anarchism and Abolition.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

William C. Anderson: A lot of people are looking for answers. Sadly, I’m afraid that if many of the places people have gone to look for generations could solve our problems, the world wouldn’t be in the predicament it’s in. And this applies to so much of what people idealize in struggle and make holy. The fascists have power and they’re preparing, if not already prepared, for war. Meanwhile, much of what’s called “the left” is fixated on nonsensical debates and revising history because they cannot face their own failure in the present. So, what can it help them understand? It can help them understand that we need to call much more into question. Black anarchism and Black autonomous radicalism is an ideological shift that gives an example of how to make use of what works and discard what doesn’t. That’s why the neglected interventions offered by them are of the utmost importance. It shows us how to fight and reject dangerous iterations of state violence that come from the right and the left in a way that has to be discussed in order to move beyond dead, perfunctory politics. It takes abolition to the state, beyond the state and also takes it deeper, inside all of us and our perception of the world around us.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

The past is a guide that we have to be critical of, not try to mimic or automatically venerate. Many people have what I feel is a very concerning and dangerous relationship with the past because they make people who were full of faults, abuses, and contradictions into infallible legends. When we observe history truthfully and carefully, we can move accordingly in our own work. Everyone isn’t an organizer, but everyone can find a place in our struggle with what they have to offer. Groups like the Black Panther Party had plenty of infighting, abuses, and conflicts. Revolutions like the Russian Revolution had plenty of betrayals, injustices, and failures. Rather than look at organizations or historical events unthinkingly, people should observe them sincerely and take what worked and go from there. Things fail repeatedly and abuses reappear when people emphasize icons and overlook the collective, rank-and-file contributions. That’s who makes history and revolution. That's where the real truth is. Many lessons are lost overemphasizing glory, leadership, and authority. So, this can help us navigate how to take something like the revolutionary intercommunalism of the Panthers and make it work today without pretending everything went right with the Party or that revolutionary Black nationalism has all the answers. We need to build survival programs, but we also need mutual aid. They aren’t the same and have very different meanings, but they don’t have to be in conflict with one another because of ideological devotion. Don’t reject what works because of doctrinaire devotion. Study widely, genuinely, and build. Keep an open mind.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

I want to dismantle preoccupation with state reform, state-building, and state seizure in whatever forms they come. I’m not fighting for so-called “revolutionary” police, borders, and militarism. I want anyone who needs to do so, to break free from the chains of dogma and let go of rigid orthodoxy. The U.S. left is not nearly as much of an oppositional force as it thinks. It’s splintered into factions where too many people romanticize any and everything that’s associated with their ideological past and present. So, you end up with people clinging to old propaganda and stale ideas. Nothing that looks the way the U.S. left does is going to overthrow anything. The absurdity can be embarrassing, but you have to recognize you’re absurd to be embarrassed about it. I certainly have before. Fortunately, one thing I learned from organizing and being around radicals who are more effective than I was is that people don’t need the vanguardism many assume they need. Self-organization happens all of the time and we’ve seen how naturally people took to mutual aid, survival programs, and more during this pandemic. The organic, growing interest in anarchism is evidence of what I’m trying to say in this text. However, I’m not trying to bring Black anarchism into the classical anarchist canon, which I both respect and criticize. I’m also not trying to make it an infinitely applicable doctrine. That’s the thinking I’m trying to get away from. We have to move beyond the nation, the state, and conventional leftism. Monopolized violence and trying to build a “revolutionary” state are not the solution. State reform and trying to alter its core functions shouldn’t be the destination. It’s a danger to the world in many of its variations.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

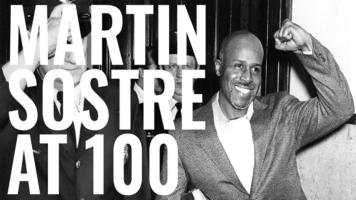

As I try to make clear throughout the book and other things I’ve written so far, I think the idea of the hero is something I’d like to move away from. There are too many to name, but these are some people who influenced me: my mother, Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, Saidiya Hartman, Nawal El Saadawi, Modibo Kadalie, C.L.R. James, Dionne Brand, Frantz Fanon, Lucy Parsons, Martin Sostre, Karl Marx, Aimé Césaire, Malcolm X - el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, Gwendolyn Brooks, Keorapetse Kgositsile, Cedric Robinson, Audre Lorde, Mariame Kaba, Lucille Clifton, June Jordan, JoNina Ervin, Eusi Kwayana, Sylvia Wynter, Gil Scott Heron, Sonia Sanchez, and the list goes on and on. My closest friends and loved ones are also some of my greatest inspirations and they constantly challenge me and dare me to go further, even when I’m scared. I’ve also been deeply influenced by the iconoclasm of Zen and its foundations with teachers like Bodhidharma and Lin-chi among other foundational monks. The music of Camille Yarborough, Alice Coltrane, Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, and others also deeply inspires my work.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

I’m trying to inspire new worlds by talking about the people, places, and ideas in this one that are overlooked and ignored because they dare to go against prearranged narratives. We aren’t going to have a new world if we refuse to acknowledge all of the mess that exists in the one we’re already dealing with. People like to pretend their corner of this messed up scenario is clean, but none of it is. There’s dirt everywhere and those in denial of this have chosen to anesthetize themselves with fairytales, myths, and overzealous nostalgia. I’m trying to struggle with people who want more and encourage others who are tired of all the nonsense so we can move forward with integrity. The new world can come from formations that are brave enough to transcend the stories we like to tell ourselves about ourselves. The much bigger confrontation we need that would flip everything on its head – known as liberation – cannot happen until we’re willing to confront what’s in the mirror.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.