In white patriarchy-ruled South Carolina at the turn of the 20th century, manhood sometimes created temporary yet tenuous bonds between Black and white men.

“White men authorized themselves to determine when Black men had suffered long enough in prison for engaging in consensual sex with a white prostitute.”

(In this four-week symposium, we asked authors to comment on Sarah Haley’s book, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. This week’s contributor is Rhondda Robinson Thomas. Read the first part of the symposium, by Marisa Fuentes, here, the second part, by Jennifer Leath, here, and the third part, by Dan Berger, here.)

“Disreputable Women, Black Clemson College Convicts, and the Patriarchal Pardon System in Post-Reconstruction South Carolina”

Rhondda Robinson Thomas:

In July of 1890, Amelia “Mealy” Bolling, a Black woman from Greenville, South Carolina, asserted in sworn testimony that she had not given her husband, Black American Wesley Bolling, any reason to be jealous of her interactions with a Black man named W. Beauregard Walker. She had simply talked with Walker in a field near her home where her husband confronted them and picked a fight with Walker. Amelia Bolling also claimed her husband had previously given her two licks. In his sworn testimony, however, Wesley Bolling contended that he became suspicious when he saw Walker follow his wife to the field, so he went after them, concealing himself in some bushes and eavesdropping on their conversation. Wesley Bolling declared that he heard Walker ask his wife if she was seeing other men, threatened to leave her if she ever did, and assured her that he could take care of her. He then inquired if her husband treated her well. If she felt mistreated, Walker suggested that they elope and move to Florida. Finally, he insisted that they go to the springs and have sex. At that moment, Wesley Bolling testified that he jumped out of the bushes and exclaimed, “I have caught you at last!” Walker grabbed a hoe to attack Wesley Bolling who fought back with a knife, striking Walker repeatedly as he ran away from the field. Walker later died of his wounds.[1] Wesley Bolling was soon convicted of murder, sentenced to two years of hard labor in the state penitentiary, and leased to help build Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina.

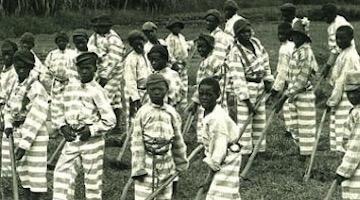

Just a few months earlier, the SC governor had signed a bill to accept the bequest of American statesman John C. Calhoun’s former estate, the Fort Hill Plantation, in the will of his son-in-law Thomas Green Clemson for the establishment of Clemson College for white males in Upstate South Carolina. The Clemson trustees’ biggest challenge in developing their school was a lack of funds. They solved their problem by tapping into the state’s convict-lease system.[2] By the late nineteenth century, South Carolina was actively engaged in hiring out convicts to supply laborers for its modernization after Reconstruction ended.[3]

“Clemson College solved its problem by tapping into the state’s convict-lease system.”

The vast majority of the nearly 700 convicts, aged 12 to 77, who were assigned to Clemson College between 1890 and 1915 were BlackAmericans like Wesley Bolling, and the prison records for those men and boys shape our understanding of the complex forces that impacted their lives, including their varied relationships with women. In penitentiary records, convicts are categorized by prison number, demographics, crime, sentence, and even distinguishing body features. Yet snippets of their voices are inscribed in primary documents such as indictments and sworn testimony. Pardon records contain information that offers a greater context for the lives of a few men like Wesley Bolling who regained their liberty through petitions, occasionally augmented by their own pleas for mercy. These pardon papers reveal the ripple effect of incarceration on the family, particularly on women. The voices in the pardon records sometimes include those of women like Amelia Bolling whose “disreputable” character becomes the means by which influential white men and working class Black men successfully make a case for the pardon of Black male convicts.

Pardon Me: A Bi-Racial Coalition Built on Men’s Honor & Honesty and a Woman’s Virtue & Dishonesty

“Black women who sought to protect themselves from domestic violence and exploitation faced the disavowal of their experiences as legal actors and prison authorities reinscribed violation as a normative part of the black female condition.” – Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here

A few months after Wesley Bolling was leased for the Clemson College convict crew, the white jurors who had voted to convict him began drawing up a petition for his release. Upstanding whites in the community characterized Wesley Bolling as a “darky of remarkable truth and veracity, honest and industrious,” according to his lawyer W. Christie Benet. Indeed, community members who signed the petition for Bolling’s “free and unconditional” pardon described him as “one who has always had the esteem and good will of the best people where ever he has lived both white and colored.” Petitioners even included some members of the Clemson College staff.[4]

“Upstanding whites in the community characterized Wesley Bolling as a ‘darky of remarkable truth and veracity, honest and industrious.’”

The petitioners coalesced around the issue of honor in justifying their petition for Wesley Bolling’s pardon. They asserted, “. . . we believe he took the live [sic] of the deceased in defence [sic] of the virtue of his wife and home, and did no more than any true honest man, white or colored, would have done under the same circumstances.” The jurors expressed identical sentiments. All but one submitted a letter of support for the pardon. On December 23, 1891, Governor Benjamin R. Tillman pardoned Wesley Bolling after he served about 13 months of his two-year sentence.[5]

Yet Amelia Bolling’s testimony had contradicted her husband’s. She intimated that he had been physically abusive and insisted that her interactions with Walker were platonic. White and Black community members not only sided with her husband, several claimed Amelia Bolling had assured them that her husband’s recollection of the events leading to the killing were “substantially true.” In essence, they intimate that Amelia Bolling was dishonest, though at least one juror had claimed Wesley Bolling had acted to protect his wife’s virtue. But her characterization of her husband’s testimony as “substantially true” indicates that she may not have fully agreed with his assessment of the incident that led to Walker’s death. No one questioned Wesley Bolling regarding his wife’s accusation of domestic violence. Instead, jurors and petitioners appropriated her supposed virtue to establish Wesley Bolling’s honesty and manhood, qualities that they deemed essential for mercy in this patriarchal pardoning system.

Before Scottsboro: The Charleston Nine, a White Prostitute, Life Sentences—then a Pardon

“An absolute notion of white feminine vulnerability that was not contingent upon wealth or social status was necessary to fortify the ideology of white supremacy that held that racial caste was required to defend the New South against the pervasive threat of rape by black men.” – Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here

South Carolina’s pardoning system functioned differently in situations involving Black men and white women, however, particularly for alleged crimes of a sexual nature. In “A Shocking Crime: Negroes Assault and Rob a White Woman in the City” published by The Charleston News and Courier on February 11, 1896, the reporter asserted, “Nine negroes were arrested yesterday morning before daybreak charged with having committed a crime too fiendish and diabolical in its details to even admit of an attempt at a description.”[6]The nameless men had been charged with committing the felonious crime of assault and highway robbery against a white female a few days earlier. In this case, the victim, Bertie Brouthers, was “a white woman, a woman of disrepute, but nevertheless a weak, dependent creature and therefore deserving of the protection which the law should afford.”[7] Initially, Brouthers’ white skin enabled her to be recognized as a prostitute but protected as a lady by a patriarchal court system controlled by white men. Bertie first reported that several “burly negroes” brutally assaulted and robbed her in an alley near a restaurant in downtown Charleston.[8] Nine Black men were arrested: Alfred Fraser alias “Cock Robin,” Thomas Rivers alias “Brick-dust”, Thomas Brown alias “Froggy,” John Simmons, Plimmer Young, Nathaniel Jackson, Sylas Guess, William Ponteau, and Samuel Smalls.

“Initially, Brouthers’ white skin enabled her to be recognized as a prostitute but protected as a lady by a patriarchal court system.”

Charlestonians crowded the courthouse for the trial on March 12, 1896, but the judge dismissed all women, white and Back, and boys under the age of 20, as mandated by law due to the salacious nature of the trial.[9] About a week after the trial began, eight of the nine men were found guilty: three received life sentences at hard labor in the state penitentiary; five were sentenced to 30 days in the Charleston County jail at hard labor; and one was released. The three sentenced to life in prison failed to win an appeal of their conviction.[10] By the early 1900s, the state had leased them to Clemson College trustees to continue the institution’s building program.

After the men had served 12 years of their life sentences, however, Henry F. Welch, foreman of the jury, initiated a process to have them pardoned. In the intervening years, the jurors’ perceptions of Brouthers had come to light. The petitioners, mostly distinguished white Charlestonian businessmen, viewed Brouthers as a woman of “most disreputable character; a common prostitute” and wished she could have been prosecuted for engaging in interracial sex.[11] In a letter to SC Governor M. F. Ansel, Attorney M. Rutledge Rivers further asserts that Brouthers only filed charges “to protect herself from the degradation of the charge of associating sexually with negroes, charged them with the offense named.”[12] Here she expresses some understanding of the societal definitions of white womanhood, regardless of her social status. Apparently, Brouthers had been drinking with the men. Only after three of the men received life sentences did she admit she had willingly associated with them and request that they be freed.[13] Brouthers’ whiteness afforded her “protection which the law should afford,” but not the liberty of convicted Black rapists. Furthermore, the men were tried just after South Carolina had outlawed interracial marriage in the 1895 constitutional convention.[14] Yet the men’s harsh sentences and the petitioners’ responses reflected white male business class Charlestonians’ public disdain for consensual, interracial sexual intercourse as well.

Although Welch was convinced the Black men and Brouthers had engaged in consensual sex, he waited 12 years to initiate the pardon process. He located all of the jurors except one who agreed that the men had suffered enough and supported their release. They all wished they had been given another option for sentencing, as they initially believed it was too harsh.[15] But none of them had publicly supported the Black men during the trial or questioned Brouthers’ initial version of the incident. They followed the law. Judge A. S. Bethea granted the pardon on April 24, 1909.

”The petitioners wished she could have been prosecuted for engaging in interracial sex.”

In the late 1800s, the actions of “disreputable women,” both Black and white, were occasionally used by the carceral state of South Carolina both to imprison and pardon Black convicts. In one case, Black and white men formed a coalition to secure the pardon of Wesley Bolling, an honorable man convicted of killing a man who had threatened the sanctity of his marriage and home. In another case, white men authorized themselves to determine when Black men had suffered long enough in prison for engaging in consensual sex with a white prostitute. Although Black and white women were constructed in opposition to each other as the Black Sapphire versus the white lady in the late 19th century, the experiences of Amelia Bolling and Bertie Brouthers suggest that manhood created temporary yet tenuous bonds between Black and white men for the pardon of Black Clemson convicts at the expense of women they deemed “disreputable.”

Rhondda Robinson Thomas is the Calhoun Lemon Professor of Literature at Clemson University.

[1] Indictment for Murder, Wesley Bolling Witness Statement, Amelia Bolling Witness Statement, The State of South Carolina, County of Greenville, Court of General Sessions, July 1890.

[2] Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1890. 299-302. Columbia, SC: James H. Woodrow, State Printer, 1891. Google Books. 299-302.

[3] Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1880. Columbia, SC: James H. Woodrow, State Printer, 1881. Google Books. 168.

[4] Bolling, Wesley. Gov. Benjamin R. Tillman’s Papers. Petitions for Pardon. Greenville County. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Columbia, SC.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “A Shocking Crime: Negroes Assault and Rob a White Woman in the City.” The (Charleston, SC) News and Courier. 11 February 1896: 1.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “The Courthouse Crowded: Eight Negroes on Trial for a Serious Crime. Much Interest Shown.” The (Charleston, SC) Evening Post. 12 March 1896: 1.

[10] Nathaniel Jackson, Sylas Guess alias “Frog,” Thomas River alias “Brick-dust,” William Ponteau, Thomas Brown, George Simmons, Samuel Small, Alfred Fraser alias “Cock Robin,” Plimmer Young, Indictment for Rape, The State of South Carolina, County of Charleston, Court of General Sessions, February Term, 1896.

[11] Small, Samuel, George Simmons, and Thomas Rivers. Gov. Martin F. Ansel’s Papers. Petitions for Pardon. Charleston County. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Columbia, SC.

[12] M. Rutledge Rivers to Hon. M. F. Ansel. 16 July 1908. Small, Samuel, George Simmons, and Thomas Rivers. Gov. Martin F. Ansel’s Papers. Petitions for Pardon. Charleston County. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Columbia, SC.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Constitution of the State of South Carolina, Ratified in Convention, December 4, 1895, Abbeville, SC: Hugh Wilson, 1900. Article III, Section 33. http://www.carolana.com/SC/Documents/South_Carolina_Constitution_ 1895.pdf.

[15] Small, Samuel, George Simmons, and Thomas Rivers, Petition for Pardon.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com