In this feature, we interview organizers, journalists, scholars, and athletes working at the intersection of sports and Black struggle. We ask three general questions to all contributors and two questions related specifically to the contributor’s area of expertise.

This week, we interview Courtney Cox. Dr. Courtney M. Cox is an assistant professor in the Department of Indigenous, Race, and Ethnic Studies at the University of Oregon. Her research examines issues related to identity, technology, and labor within sport. Her current book project, Double Crossover: Gender, Politics, and Performance in Basketball, considers how Black women and nonbinary athletes maneuver through the global sports-media complex. She is also co-director (with Dr. Perry B. Johnson) of The Sound of Victory, a multi-platform digital humanities project located at the intersection of music, sound, and sport. She previously worked for ESPN, Longhorn Network, NPR-affiliate KPCC, and the WNBA's Los Angeles Sparks.

Roberto Sirvent: What sports headline or controversy is grabbing your attention these days?

Courtney M. Cox: As someone deeply concerned with labor issues in sport, I keep returning to the race-norming lawsuit in the NFL where Black athletes were assumed to have a lower baseline cognitive function, which affected whether these retired players qualified for the league settlement or how much they were compensated. In a moment where there is so much focus (rightfully so) on the dearth of Black NFL head coaches, I’ve been sitting with the larger structural, institutional aspects of the perceived intellectual inferiority of Black folks in the NFL and how that continues to circulate in a myriad of ways. This is not only the things we know outright – the differences in how Black and white quarterbacks are retained by teams or even covered by media outlets, for example – but it also lingers in all of the emails and text messages that have been “uncovered” as of late. I’m also really interested in how mental health in sport is moving into a lot of mainstream conversations – it’s one of the main things that students are interested in unpacking as well. If I can have a third obsession, it would have to be Athletes Unlimited (AU) and the possibilities that come with an athlete-driven league. I’m extremely into what’s going on with women’s hoops within this space, but also excited about future possibilities for the other sports under this AU umbrella. I’m hoping that the WNBA and the journalists that cover the league are taking notes.

You teach a class called “Race, Culture, Empire: The Olympics.” Why is it important to think about racism and imperialism when studying the Olympics?

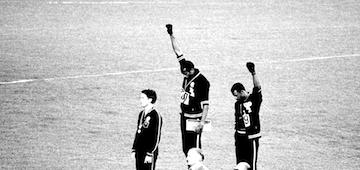

For me, it’s rather difficult to talk about the Olympics without bringing nation and identity into the conversation. I mean it’s infused into the Games past and present and made vivid by the spectacle of medal counts, ceremonies, and national anthems played at the podium. It is impossible to untangle issues of race and equity more broadly in this space when we look at who comprises the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Executive Committee (primarily white, Western, men) or who makes key decisions for athletes within the Court of Arbitration for Sport. I think the examples that stand out to a lot of people – the 1936 Berlin Olympics (often referred to as the “Nazi Olympics”) or Tommie Smith and John Carlos with their fists in the air on the podium – are really important highly-mediated moments. However, the very foundation of the Games themselves constantly reify the nation-state, determining what countries are legible to the IOC, how sporting citizenship operates, and how protest against a nation (one’s own or another) is regulated. In my class, we delve into the origins of the modern Games and consider how scientific racism (i.e., Anthropology Days), colonization, imperialism, and warfare continuously shape what we see in the Summer and Winter Olympics. We also, of course, watch a lot of elite athletes at their best.

Can you please share a little about your current book project about Black women and non-binary athletes?

Throughout the book, I employ the metaphor of the crossover, a spectacular basketball move, to describe how Black women and nonbinary athletes maneuver through a sporting industry not designed with them in mind. While it isn’t as flashy as a dunk or as violent as a block, the crossover is about agility, balance, and deception. It demands rapid lateral movement with seemingly little effort. It also requires a particular sense of poise and control to challenge an opponent’s balance, leaving adversaries helpless as they flail, trip, or crash to the ground (referred to on the court as “breaking ankles”). The crossover relies upon an athlete knowing where they are on the court and where they need to go. Shifting from one side to the other rapidly and following an internal rhythm, the well-timed crossover allows one to create space for themselves and their teammates, ultimately allowing for a clear path to the basket. In taking up the crossover as a conceptual framework centering Black athletes, specifically those who identify as women or nonbinary, I argue that the experiences and strategies cultivated by these athletes provide an instructive lens into the proliferation of basketball as 1) global industry grounded in different modes of production, consumption, and media; and 2) a site of global spectacle, fantasy, and struggle. On both these fronts, players, journalists, coaches, and executives navigate, negotiate, and resist countless boundaries and obstacles. Amid institutional and economic inequities and gendered and racialized stereotypes, they create community and generate new forms of knowledge—new means of maneuvering, wiggling in and out and around defenders, sidestepping opponents, and as some would say on the basketball court, "putting the world on skates."

How did you become interested in studying race, sports, and politics?

I’m often asked if I’m a current or former athlete by folks within academia (but never by athletes or coaches!). I peaked athletically in middle school, but still wanted to be a part of sports in some way. In high school, I worked briefly as an athletic trainer; in college I worked at the rec center on campus and for my university’s athletics department. I didn’t quite know what I wanted to do with sports, but it was this constant in my life. I majored in broadcast journalism in undergrad, and my first job out of college was at ESPN, where I worked in event production and studio directing. When Longhorn Network (a 24-hour station dedicated to The University of Texas Longhorns) launched, they moved a lot of Texas folks there (including me!), and I had the opportunity to return to my alma mater for a graduate degree. I was working full-time in control rooms and live trucks at night and in a M.A. program full-time in the morning. I realized that I really loved the classroom and getting nerdy about my passions – far more than I thought I would – and my research agenda formed directly from my experiences in sports media. I eventually made the full pivot to academia and haven’t looked back!

Which books have most impacted the way you theorize about sports and Black struggle?

My work is indebted to so many different thinkers and scholars across a variety of fields. I’m so frequently elevated by the work of athletes, whether it’s in op-eds, tweets, Instagram posts, or their own memoirs. I am most inspired by Black feminist texts such as Patricia Hill Collins’s Black Feminist Thought, Aimee Meredith Cox’s Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship, bell hooks’s Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism, and Katherine McKittrick’s Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. While these books aren’t about sports at all, they frame my approach and guide me in centering my work from my own standpoint. When I think about books that continue to impact me specifically within sport, I’m carried by Samantha N. Sheppard’s Sporting Blackness: Race, Embodiment, and Critical Muscle Memory on Screen, Gena Caponi-Tabery’s Jump for Joy: Jazz, Basketball, and Black Culture in 1930s America, and the fantastic collection Basketball Jones: America Above the Rim edited by Todd Boyd and Kenneth L. Shropshire. There’s obviously a bit of recency bias here given my current project involving basketball – I’ve been thinking about it a LOT. However, I think so many of the arguments across these texts resonate across both sport and society. Finally, I have to shout out Ben Carrington’s Race, Sport and Politics: The Sporting Black Diaspora, Janelle Joseph’s Sport in the Black Atlantic: Crossing and Making Boundaries, Munene Mwaniki’s The Black Migrant Athlete: Media, Race, and the Diaspora in Sports, and Damion L. Thomas’s Globetrotting: African American Athletes and Cold War Politics as key texts that continue to expand my framework in terms of movement, migration, and diaspora.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.