In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Malcolm Harris. Harris is a freelance writer and the author of Kids These Days: The Making of Millennials and Shit is Fucked Up and Bullshit: History Since the End of History. His book is Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Malcolm Harris: When I first started this project, I anticipated having a hard time convincing critics that Palo Alto/Silicon Valley is a world-historically important site in the 20th century and that it's worth understanding its dynamics all the way to their roots. I don’t have those concerns any more; now I have to stop myself from talking about my research in connection with the headline news every day.

One thing Palo Alto offers — and I know this sounds counter-intuitive since the book is very long — is that it shows how short the historical period is. The Anglo history of California is like 150 years old; that’s a handful of generations. The indigenous people literally buried under Silicon Valley are not ancient by any means, we know some of their names and their living family members.

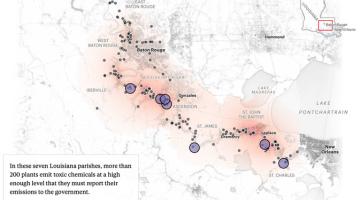

This century-and-a-half is the era of planetary capitalism, and California and particularly the Bay Area has played a central role over the period as an experimental lab for the ruling class. How to stay on top of a rapidly spinning world has been an extremely fraught question for them, and our current climate is in many ways a direct result of the particular answers they developed, in California and especially Palo Alto. Some of those answers have to do with computers, but the core dynamics are more fundamental than that; they apply to the production of horses and apricots too, as well as intangibles like the idea of IQ or whiteness.

The takeaway from the book isn’t the perfunctory answer “It’s capitalism” — that’s just the premise.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

The book is a history of capitalist relations, and so one way I always thought about it was in the two dialectical halves, capital and labor, and the mutually constitutive struggle between them. I’m lucky to benefit from the work by so many left-wing historians in the past couple decades to trouble the conventional stories of progress. They’ve succeeded to a certain degree: Du Bois’s argument in Black Reconstruction, for example, is an increasingly common way to consider the afterlife of American slavery, and that’s in large part thanks to scholar-activists who have worked against the grain to detail that story of continuity. And I think many activists and organizers now have a stronger sense of the nature of social change, which has been shaped by their informed attempts to move, to put that knowledge into action. The result has been a neo-abolitionist framework that I think represents some of the most advanced politics of my lifetime.

My hope for Palo Alto, then, is that the active, political reader — and it’s written to an active, political reader, though perhaps not only to them — gets a better sense of what exactly they’re up against, where the capitalist mode is tensile and where it’s brittle. A historically informed sense of the system’s range of movement is invaluable for thinking strategically. What can capital accommodate? How and why? Contrariwise, what can’t the system handle. And, last but not least, How does it handle what it can’t handle? To my mind, that’s the most important question in our present moment: How does capitalism handle what it can no longer handle? I hope Palo Alto has some answers there.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

It was incredibly valuable for me to work through the history of that struggle in the place where I grew up; like a lot of Americans I was taught a particular liberal progressive account of the 20th century, but going back through that history, it’s striking how recurring the same problems are, that so much of what we’re taught about progress is really a story of shifting tactics and strategies by the ruling class.

Silicon Valley is very good at self-mythologizing, and I hope I help readers see behind the curtain, in part by showing them how tech — from the first transistors to the internet — actually works and how (and by whom, and under what circumstances) it’s built. What that ends up meaning is that I spend much of the book stitching together traditional histories of the region with global history, specifically 19th-century colonialism and the 20th-century decolonization struggle and the neocolonial reaction. That’s a different frame for American history than the one we usually get, and, as I make the case, a better one.

When readers think about California, I don’t want them to think about some fantasy land outside of history. I want them to think about Algeria and the Philippines and South Africa and Vietnam and Australia and Manchuria. In 1858, Karl Marx mused to Friedrich Engels that, with the world market finally linking the American and Asian continents through California and China, capitalist forces had a way to defeat the socialist revolution brewing in Europe and preserve class domination into the future. I see my project as an exploration of that correct prediction.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

Marx and Marxism. It’s such a varied tradition that one has to be more specific, but I don’t see any point in pretending or hedging on the question. Palo Alto opens with Marx’s request for a big book about economic conditions in California because he saw it as a crucial step in the history of capitalist development as well as its most dramatic example. And there are only a few steps between then and now: Paul Baran, co-author of Monopoly Capital and Stanford economist, is two degrees of separation from Marx. Baran was hugely influential for west-coast radicals in the ‘60s, particularly the Black Panther Party, as well as the Third-World movement abroad.

I grew up in Palo Alto trawling the used bookstores for cool old paperbacks. So I was inspired by these movements behind my back. The copies of Black Power or The Affluent Society or Man’s Fate or The Theory of the Leisure Class or Soledad Brother that I read as a teen were put there by people who read them as part of a particular program of study and struggle, though I wasn’t aware of that exactly. Which is to say, I feel like Marxism has been interested in me longer than I’ve been interested in Marxism.

In Palo Alto, I get to do some untangling. By the end, I couldn’t help but feel like part of a very specific intellectual tradition of California communism, one that stretches from the transnational Pacific revolutionary networks of the early 20th century and the Industrial Workers of the World, through the renegade west-coast CPUSA, into the left wing of the New Left and the New Communist Movement. That gets you from the Second International to like Bay Area punk bands from when I was a kid.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

I’ll pick two that are special in their relationship to Palo Alto because the authors are in there both as participants in history and as interpreters. They’re also both theorists who I see as part of the California communist tradition, and I hope to work more on that in the future as an explicit rather than implicit subject.

One is Mae Ngai’s newest book, The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes, Chinese Migration, and Global Politics. This one’s not exactly unheralded — it won the Bancroft Prize — but Ngai’s account of Chinese migrant labor in Anglophone settlements in the second half of the 19th century is a helpful recontextualization that overturns long-common stereotypes. More than that, with its focus on international labor flows, racial formation, and gold extraction, it’s a case study of a capitalism we can still recognize.

Another book is Cedric Robinson’s recent posthumous collection, On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance. Best known for Black Marxism, this collection edited by H.L.T. Quan is an excellent introduction to his work. From a critique of race in Aristotle’s thought, to neocolonialism in the Philippines, to Eugene O’Neil, to blaxploitation, to ‘90s California current events, the book reveals a staggeringly nimble mind. Also check out Joshua Myers’s new biography of Robinson, Cedric Robinson: The Time of the Black Radical Tradition.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.