Britain is, indeed, the “mother country” of US white supremacy, having bythe 13th century become “The First Racial State in the West.”

“As time passed, it was London’s model, then accelerated by Washington, that prevailed,: focusing enslavement tightly on Africans and those of even partial African ancestry.”

The following is an excerpt from Gerald Horne’s book, The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century. It is re-printed with permission from NYU Press and Monthly Review Press.

Introduction

It should not have been deemed surprising when in 1977 Washington’s ambassador to the United Nations—Andrew Young, a former chief aide to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—asserted audaciously that London “invented” racism. Instead, the pastor-cum-diplomat was pelted ferociously in a hailstorm of invective,1 as he backpedaled rapidly. Actually, London had a point it did not articulate: if anything, its bastard offspring in Washington, in the government the envoy represented, was probably more culpable for the continuation of this pestilence,2 as it lurched into incipient being in the 1580s in what is now North Carolina and gravitated toward a model of development that diverged from those spurred by the Ottomans and Madrid, then rebelled in 1776 to ensure this putridness would endure.3 How and why this deadly process unfolded in its earliest stage rests near the heart of this book.

Still, Ambassador Young, an ordained Protestant minister, would have better served historical understanding (besides providing useful instruction to predominantly Protestant London) if he had reflected on the point that the rise of this once dissident and besieged sect in the North American settlements led to the supplanting of religion as an animating factor of society with “race,”4 a major theme to be explored in the pages that follow.5 Certainly “whiteness”—effectively, Pan-Europeanism—provided a broader base for colonialism than even the Catholicism that drove Madrid. Historian Donald Matthews has observed that white supremacy in any case—a ruling ethos in London’s settlements, then the North American Republic—had a religious cast, indicative of its tangled roots, with lynchings of Negroes emerging as a kind of sacrament.6

“’Whiteness’—effectively, Pan-Europeanism—provided a broader base for colonialism than even the Catholicism that drove Madrid.”

Ambassador Young would also have better served understanding if he had had the foresight to reflect the penetrating view of the eminent scholar Geraldine Heng, who has argued that at least by the thirteenth century, England had become “The First Racial State in the West,” referring to the pervasive anti-Judaism that then prevailed. And just as it became easier to impose an expansionist foreign policy that propelled colonialism, given the experience with the Crusades, likewise it became easier to impose the racism that underpinned settler colonialism and slavery, once anti-Judaism became official policy in London. As U.S. Negroes were to be treated, the Jewish community in England was said to emit a “special fetid stench,” while bearing “horns and tails” and engaging in “cannibalism.” Religion was deployed “socio-culturally” and “bio-politically” to “racialize a human group” in England in a manner eerily similar to what was to unfold in North America. Certainly, there are differences that distinguish anti-Judaism from anti-Negro bias. The persecuted in England were “unable to own land in agricultural Europe,” but in response, “Jews famously established themselves as financiers,” a status generally unavailable to Negroes, though the ban on landowning was. Interestingly, though this murderous bigotry is understandably associated with Madrid, which dramatically expelled the Jewish community in the hinge year that was 1492, it was London that was the first European country to “stigmatize Jews” as “criminals”—another parallel to U.S. Negroes—and the “first to administer the badge” this community was forced to wear. England was the first to initiate “state-sponsored efforts at conversion” and, more to the point vis-à-vis Spain: “the first to expel Jews from its national territory.” Then it was the prevailing religion, says Heng, that “supplied the theory and the state and populace supplied the praxis” of bigotry, analogous to the deployment of the “Curse of Ham” and racism targeting U.S. Negroes. Fear of “interracial sexual relations” was then the praxis in London, just like it was subsequently in Washington.7 Ironically and perversely, London’s earlier bigotry positioned England to capitalize upon Madrid’s later version, by appealing to Sephardim and the Jewish community more broadly that had been perniciously targeted by the Spanish Inquisition.

“Religion was deployed ‘socio-culturally’ and ‘bio-politically’ to ‘racialize a human group’ in England in a manner eerily similar to what was to unfold in North America.”

This is a book about the predicates of the rise of England, moving from the periphery to the center (and inferentially, this is a story about their revolting spawn in North America post-1776). This is also a book about the seeds of the apocalypse, which led to the foregoing—slavery, white supremacy, and settler colonialism (and the precursors of capitalism)—planted in the long sixteenth century (roughly 1492 to 1607),8 which eventuated in what is euphemistically termed “modernity,” a process that reached its apogee in North America, the essential locus of this work. In these pages I seek to explain the global forces that created this catastrophe—notably for Africans and the indigenous of the Americas—and how the minor European archipelago on the fringes of the continent (the British isles) was poised to come from behind, surge ahead, and maneuver adeptly in the potent slipstream created by Spain, Portugal, the Ottomans, even the Dutch and the French, as this long century lurched to a turning point in Jamestown. Although, as noted, I posit that 1492 is the hinge moment in the rise of Western Europe, I also argue in these pages that it is important to sketch the years before this turning point, especially since it was 1453—the Ottoman Turks seizing Constantinople (today’s Istanbul)—that played a critical role in spurring Columbus’s voyage and, of course, there were other trends that led to 1453, and so on, as we march backward in time.9

In brief, and as shall be outlined, the Ottomans enslaved Africans and Europeans, among others, as contemporary Albania and Bosnia suggest. The Spanish, the other sixteenth-century titan, created an escape hatch by spurring the creation of a “Free African” population, which could be armed. Moreover, for 150 years until the late seventeenth century, thousands of Filipinos were enslaved by Spaniards in Mexico,10 suggesting an alternative to a bonded labor force comprised of Africans or even indigenes. That is, the substantial reliance on enslaved African labor in North America honed by London was hardly inevitable.

“The Spanish created an escape hatch by spurring the creation of a ‘Free African’ population, which could be armed.”

Florida’s first slaves came from southern Spain, though admittedly an African population existed in that part of Europe and wound up in North America. Yet at this early juncture, sixteenth-century Spanish law and custom afforded the enslaved rights not systematically enjoyed in what was to become Dixie. Moreover, Spain’s shortage of soldiers and laborers, exacerbated by a fanatical Catholicism that often barred other Europeans under the guise of religiosity—a gambit London did not indulge to the same extent—provided Africans with leverage.11

However, as time passed, it was London’s model, then accelerated by Washington, that prevailed,: focusing enslavement tightly on Africans and those of even partial African ancestry, then seeking to expel “Free Negroes” to Sierra Leone and Liberia. London and Washington created a broader base for settler colonialism by way of a “white” population, based in the first instance on once warring, then migrant English, Irish, Scots, and Welsh; then expanding to include other European immigrants mobilized to confront the immense challenge delivered by rambunctious and rebellious indigenous Americans and enslaved Africans. This approach over time also allowed Washington to have allies in important nations and even colonies, providing enormous political leverage.12

This approach also had the added “advantage” of dulling class antagonism among settlers, who, perhaps understandably, were concerned less about the cutthroat competition delivered by an enslaved labor force and more with the real prospect of having their throats cut in the middle of the night by those very same slaves. Among the diverse settlers—Protestant and Jewish; English and Irish et al.—there was a perverse mitosis at play as these fragments cohered into a formidable whole of “whiteness,” then white supremacy, which involved class collaboration of the rankest sort between and among the wealthy and those not so endowed.

“Protestant and Jewish; English and Irish et al.—there was a perverse mitosis at play as these fragments cohered into a formidable whole of ‘whiteness,’ then white supremacy.”

In a sense, as the Ottomans pressed westward, Madrid and Lisbon began to cross the Atlantic as a countermove by way of retreat or even as a way to gain leverage.13 But with the “discovery” of the Americas, leading to the ravages of the African slave trade, the Iberians, especially Spain, accumulated sufficient wealth and resources to confront their Islamic foes more effectively. 14

The toxicity of settler colonialism combined with white supremacy not only dulled class antagonism in the colonies. It also solved a domestic problem with the exporting of real and imagined dissidents. In 1549 England was rocked to its foundations by “Kett’s Revolt,” where land was at issue and warehouses were put to the torch and harbors destroyed. A result of this disorienting upheaval, according to one analysis, was to convince the yeomanry to ally with the gentry,15 a class collaborationist ethos then exported to the settlements. Assuredly, this rebellion shook England to its foundations, forcing the ruling elite to consider alternatives to the status quo, facilitating the thrust across the Atlantic. It is evident that land enclosure in England was tumultuous, making land three times more profitable, as it created disaster for the poorest, providing an incentive for them to try their luck abroad. A plot of land that once employed one or two hundred persons would—after enclosure—serve only the owner and a few shepherds.16

This vociferation was unbridled as the unsustainability of the status quo became conspicuous. Palace intrigue, a dizzying array of wars, with allies becoming enemies in a blink of an eye, the sapping spread of diseases, mass death as a veritable norm, bloodthirstiness as a way of life—all this and worse became habitual. This convinced many that taking a gamble on pioneering in the Americas was the “least bad” alternative to the status quo. Indeed, the discrediting of the status quo that was feudalism provided favorable conditions for the rise of a new system: capitalism.

“The toxicity of settler colonialism combined with white supremacy dulled class antagonism in the colonies.”

As I write in 2019, there is much discussion about the purported 400th anniversary of the arrival of Africans in what is now the United States, though Africans enslaved and otherwise were present in northern Florida as early as 1565 or the area due north as early as 1526. As the following paragraphs suggest, this 1619 date is notional at best or, alternatively, seeks to understand the man without understanding the child. In my book on the seventeenth century, noted above, I wrote of the mass enslavement and genocidal impulse that ravaged Africans and indigenous Americans. That book detailed the arrival in full force of the apocalypse; the one at hand limns the precursor: the dawning of this annihilation. The sixteenth century meant the takeoff of the apocalypse, while the following century embodied the boost phase. In brief, this apocalypse spelled the devastation of multiple continents: the Americas, Australia,17 and Africa not least, all for the ultimate benefit of a relatively tiny elite in London, then Washington.

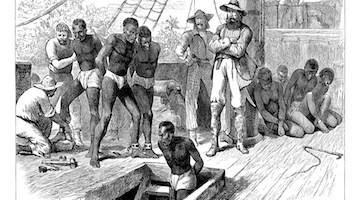

Thus, for reasons that become clearer below, the enslavement of Africans got off to a relatively “slow” start. From 1501 to 1650, a period during which Portuguese elites, at least until about 1620, and then their Dutch peers, held a dominant position in delivering transatlantic imports of captives: 726,000 Africans were dragged to the Americas, essentially to Spanish settlements and Brazil. By way of contrast, from 1650 to 1775, during London’s and Paris’s ascendancy and the concomitant accelerated development of sugar and tobacco, about 4.8 million Africans were brought to the Americas. Then, for the next century or so, until 1866, almost 5.1 million manacled Africans were brought to the region, at a time when the republicans in North America played a preeminent role in this dirty business. Similarly, at the time of the European invasion of the Americas, there were many millions of inhabitants of these continents, but between 1520 and 1620 the Aztecs and Incas, two of the major indigenous groupings, lost about 90 percent of their populations. In short, the late seventeenth century marked the ascendancy of the apocalypse, and the late sixteenth century marked the time when apocalypse was approaching in seven-league boots.18 Yet the holocaust did not conclude in the seventeenth century, as ghastly as it was. The writer Eduardo Galeano argues that in three centuries, beginning in the 1500s, the “Cerro Rico” alone, one region in South America, “consumed eight million lives.”19 Thus, due north in California, the indigenous population was about 150,000 in 1846 at the onset of the U.S. occupation, but it was a mere 16,000 by 1890,20 a direct result of a policy that one scholar has termed “genocide.”21

Notes

INTRODUCTION

1. New York Times, 8 April 1977.

2. Cf. Ivan Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America (New York: Random House, 1976), 130: Here the scholar speaks broadly of the “unconscious racial reflex of British scholars.”

3. Gerald Horne, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (New York: New York University Press, 2014).

4. Gerald Horne, The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy and Capitalism in Seventeenth Century North America and the Caribbean (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018). B.M.S. Campbell, Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late Medieval World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

5. Cf. Frank Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas (New York: Knopf, 1947): The point argued in these pages is not that Catholicism was more progressive than Protestantism in handling slavery but that the nation where the latter prevailed—that is, England—as an underdog felt compelled to move away from religious sectarianism to confront the primary foe in Madrid by allying with, for example, the Ottoman Turks and Morocco (predominantly Muslim nations); as an underdog moving away from religious sectarianism, London proved to be more flexible in forming settlements, for example, Maryland, where Catholics played a major role: likewise, Madrid was capable of embracing African conquistadors—Catholics certainly—whereas London, pressed to the wall, embraced a Pan-European project that generally was not able to make as much room for African conquerors in North America. This project continued for some time, for example, Stephen Conway, Brittania’s Auxiliaries: Continental Europeans and the British Empire, 1740–1800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

6. Donald Matthews, At the Altar of Lynching: Burning Sam Hose in the American South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017). Fortunately, some scholars of late have explored how religion helped to propel “race.” See, for example, Terence Keel, Divine Variations: How Christian Thought Became Racial Science (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018); John Hayes, Hard, Hard Religion: Interracial Faith in the Poor South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017). Tisa Wenger, Religious Freedom: The Contested History of an American Ideal (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 1, 3, 10–11: The author argues that religious liberty “helped define American whiteness and make the case for U.S. imperial rule.” Thus, “religious freedom talk” became code for “white and Protestant,” juxtaposed against “the supposed bondage of the pagan and the Catholic.” This trope of religious liberty “served as an imperial mechanism of classification and control, helping to define not only what counted as religion . . . but also the contours of the racial.” Yes, the victims of this entrapment—especially African-Americans—in a form of intellectual and theological judo, sought to deploy religion against the victimizer, but the halting nature of real progress today should suggest that this ideological grappling—turning the strength of the oppressor’s tool back against him—may have reached the outer limits of its possibilities. See also Peter Kerry Powers, Goodbye Christ? Christianity, Masculinity and the New Negro Renaissance (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017). Of course, the fifteenth century publication of the Gutenberg Bible and the technological innovation it represented marked a turning point in the rise of both literacy and dissidence within Christianity more generally. See Janet Ing, Johann Gutenberg and His Bible: A Historical Study (New York: Typophiles, 1990). See also Margaret Leslie Davis, The Lost Gutenberg (New York: TarcherPerigee, 2019) and Eric Marshall White, Editio Princeps: A History of the Gutenberg Bible (London: Miller, 2017).

7. Geraldine Heng, England and the Jews: How Religious Violence Created the First Racial State in the West (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 11, 12, 14, 20, 48, 52, 70. Cf. David M. Whitford, The Curse of Ham in the Early Modern Era: The Bible and the Justifications for Slavery (Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2009) and David M. Goldenberg, Black and Slave: The Origins and History of the Curse of Ham (Boston: de Gruyter, 2017).

8. Frederic J. Baumgartner, France in the Sixteenth Century (New York: St. Martin’s, 1995), xi: “The long sixteenth century” is referenced here.

9. Marching forward in time, the white supremacist in 2019 who massacred Muslims in New Zealand earlier visited the Balkans to study the uprooting of Christians: London Daily Mail, 16 March 2019.

10. Taina Seijas, Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

11. Larry Eugene Rivers, Slavery in Florida: Territorial Days to Emancipation (Tallahassee: University Press of Florida, 2000), 2.

12. Gerald Horne, Race to Revolution: The U.S. and Cuba During Slavery and Jim Crow (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2014); Gerald Horne, White Supremacy Confronted: U.S. Imperialism and Anticommunism vs. the Liberation of Southern Africa, from Rhodes to Mandela (New York: International Publishers, 2019).

13. Andrew C. Hess, The Forgotten Frontier: A History of the Sixteenth Century Ibero-African Frontier (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 20.

14. One scholar has “estimated that the Spanish Crown’s original investment in Columbus’s first voyage provided a return of 1, 733, 000 per cent.” See David Childs, Invading America: The English Assault on the New World, 1497–1630 (Yorkshire: Seaforth, 2012), 278.

15. Andy Wood, The 1549 Rebellion and the Making of Early Modern England (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

16. John Butman and Simon Target, New World Inc.: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (New York: Little Brown, 2018), 10, 16.

17. Gerald Horne, The White Pacific: U.S. Imperialism and Black Slavery in the South Seas After the Civil War (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007).

18. Aline Helg, Slave No More: Self-Liberation Before Abolition in the Americas (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 2019, 18, 19, 21, 22.

19. Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of The Pillage of a Continent (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973), 50. See also Peter J. Blackwell, Miners of the Red Mountains: Indian Labor in Potosi, 1545–1650 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984).

20. D. Michael Bottoms, An Aristocracy of Color: Race and Reconstruction in California and the West, 1850–1890, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), 27.

21. Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

This excerpt was edited by Roberto Sirvent, editor of the BAR Book Forum.

COMMENTS?

Please join the conversation on Black Agenda Report's Facebook page at http://facebook.com/blackagendareport

Or, you can comment by emailing us at comments@blackagendareport.com