In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured authors are Françoise N. Hamlin and Charles W. McKinney, Jr. Dr. Hamlin is Royce Family Associate Professor of Teaching Excellence in Africana Studies & History at Brown University. Dr. McKinney, Jr. is chair of Africana studies and associate professor of history at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee. Their book is From Rights to Lives: The Evolution of the Black Freedom Struggle.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Françoise N. Hamlin and Charles W. McKinney, Jr.: Our ultimate message here is that history matters and we cannot understand contemporary Black struggles against systemic racism if we do not consider the past and how it lays out a foundation for our present. From Rights to Lives reminds people that “the current social and political climate” also has a history. The policies and laws we contend with now did not materialize out of thin air. Rather, they are the extension of patterns and practices we have seen before.

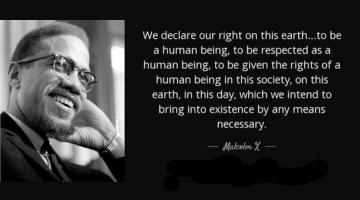

In this way, we wanted to present explicit comparisons between two masses of movements - what we know broadly as the Civil Rights Movement with Black Lives Matter – both on the longer timeline of the Black Freedom Struggle. An edited volume allows for accessibility with an array of case studies that approach the task in different ways, and with different analytical tools within the social science and humanities arsenal. Together, these chapters demonstrate the extent of systemic white supremacy and the ways in which the system constantly maneuvers to subvert democracy. With any luck, our book will help readers understand the legacies of white supremacy alongside the legacies of Black Struggle.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

We wanted to deliver a book that the people we write about and for can actually pick up and read so that they too can make the connections between these two major African American political, social, and cultural mass movements while also reinforcing why history matters. One upside of an edited volume is that readers get treated to a series of case studies; each chapter is designed to illuminate a different set of factors related to movement work. We also wanted to affirm for activists and community organizers how messy and complicated the struggle for liberation can actually be. Intergenerational tensions, gender dynamics, debates about tactics, the impact of social media, media perceptions (or misperceptions) of the movement, the science of organizing – all of these issues and more shape the trajectory of movements in myriad ways. We wanted to give our readers the opportunity to see how organizers in the past and those operating now dealt and deal with these and other dynamics and challenges.

We also hope activists and organizers will read the book and remember that they are part of a longer tradition of struggle. It can be hard to see this lineage in real time, especially in the middle of battle. It is our hope that this knowledge can serve as a powerful reminder of the shoulders upon which people stand. That knowledge brings power, responsibility, and resolution.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

By providing a number of vantage points from which readers can see historical continuities and disjuncture, we underscore that movements are messy and complicated – they require activists learning, training, and pivoting in real time, often conflicting with each other over strategy while jostling sometimes for influence. This is why the book underscores the necessity of education, particularly political education, in order to subvert, thwart, disrupt, and unlearn patterns of abuse and neglect. It relieves us of what we call the “kumbaya” myth, that everyone in the Civil Rights Movement linked arms and agreed on the way forward.

The book’s structure, a series of case studies, also highlights the locality of activism and the difficulties in maintaining national and international consensus and momentum as different locales respond to local events and needs. We live in an age where everything has sped up. We expect to receive things almost instantaneously once we have asked or demanded them. To that end, we hope the book will help people unlearn the expectation of immediacy when it comes to social change work. For example, as Peter Pihos shows us in his chapter, police reform failed in Chicago after years of effort on the part of Black police officers. Althea Legal-Miller’s chapter reminds us that, in spite of her herculean efforts, Dorothy Height met with very limited success in her attempt to secure justice for Black women activists detained and assaulted by law enforcement officers during the 1960s. Then the concluding chapter reminds readers that current local activists’ understanding of the shortcomings of previous liberator moments in Memphis aided in the success at garnering city ordinances in the wake of the Tyre Nichols police murder in 2023. Three examples when we question the meanings of success by reminding us of the long game necessary to challenge white supremacy.

Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

FH: We are both historians who primarily study and write about the Civil Rights Movement. Françoise considers the activists who entrusted her with their life stories and encounters where the lessons and knowledge that come with experience and maturity come to life as intellectuals in their own right, and include David Dennis and the late Vera Pigee. Her scholarly work in this field as a graduate student began by reading John Dittmer’s Local People (1994) and Charles Payne’s I’ve Got the Light of Freedom (1995), as the first two comprehensive studies on the Mississippi movement from the grassroots. Nevertheless, she has learned the most from the activists themselves and how they have understood the world and their place therein.

CM: As an undergraduate at Morehouse College in Atlanta, my mentor, Marcellus Barksdale, introduced me to what he called “the indigenous civil rights movement.” This was an exploration of the movement from a local level. It was an absolute epiphany. The book that set me on my course was William Chafe’s Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom. This perspective shaped the way I thought about who constituted an intellectual and how I thought of movement work. So, while I am forever indebted to Ida Wells, W.E.B. DuBois, and Martin King as formative intellectuals, I am also indebted to the Black working class women and men (and their scant few middle class allies) who laid the intellectual groundwork for survival and movement.

Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

FH: There are so many amazing books that dig deep into the lives, thoughts, and actions of Black people in the United States and across the Diaspora. It is actually impossible to pick two. So just thinking about the recent books I have taught in the past six months, the students most connected with David Dennis, Sr & David Dennis, Jr., The Movement Made Us: A Father, A Son, and the Legacy of a Freedom Ride. This book holds space for us to think about youthful activism, deep responsibility, survivor’s guilt, and generational trauma, while also learning about campaigns, place, people, and the basic historical foundations of movement making. It is readable yet rigorous and presented perfectly to allow for father and son to work together on the journey.

CM: There are so many books to choose from. But if I have to pick two, the first one would be Of Black Study by Josh Myers. This book is a foundational work, crafted by one of the foremost scholars in Black Studies. Black Study centers the work of Black thinkers who understood the limits of disciplinary exploration, folks who knew they had to go beyond the boundaries of fields like history and sociology to get to the stuff of Black life and thought. Myers’ book is a forceful reminder that Black Studies, at its best, offers a profound critique of western civilization and the ways of knowing produced in its bloody wake. The second book is Julius Fleming’s Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Work of Emancipation. Fleming’s book is an exploration of the ways in which Black artists and activists utilized theater and other arts to confront the soul-crushing, white supremacist imperative to “wait” - for freedom, equality, justice, and all the things Black folks should have had from jump. Fleming recasts the civil rights revolution as a moment where luminaries like James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Duke Ellington, and others used their art to construct a powerful counter narrative to dominant notions of what Fleming calls “black patience.” This book was an epiphany in my Civil Rights Movement course.

Roberto Sirvent is the editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.