BAR Contributing Editor Ann Garrison reports from Ethiopia.

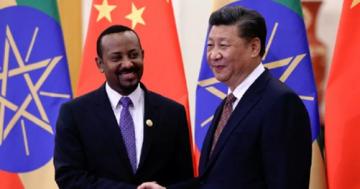

I’m writing from Ethiopia, where the war that began in November 2020 continues, with the US backing their former puppet, the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), who ruled Ethiopia with an iron fist from 1991 to 2018, when they were finally overthrown by a popular uprising.

The TPLF started the war by attacking the national army's five Northern Command bases in Tigray on November 3rd and 4th, 2020, but the West’s dominant state and corporate press narrative quickly became that Prime Minister Abiy had started the war by sending troops into Tigray, alleging the attack as his excuse. This was one of many early indicators that the US, the NATO nations, and their press were backing the TPLF.

I’ve been here for eleven days. For most of this time I’ve been traveling with American photojournalist Jemal Countess, who went home yesterday, and Ethiopian American multimedia producer Betty Sheba Tekeste. These are my observations about the first leg of our trip.

Lalibela: Churches, water, electricity, and a surgical strike

After landing in the capital, Addis Ababa, I flew directly to Lalibela, in Amhara Region, site of the rock-hewn Ethiopian Orthodox churches built by King Lalibela in the 12th century. The churches are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and tourism is Lalibela’s lifeblood. It was hit hard when tourists stopped traveling because of COVID at the end of 2019, then hit even harder when the TPLF occupied the town for five months, from August to December 2021. Tourists were beginning to trickle back in while I was there.

After seizing Lalibela in August 2021, the TPLF negotiated with the clergy at the churches to protect them. Damaging the churches would have been devastating PR for any parties responsible. The national army, the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), was also committed to protecting the churches, so almost all of the fighting took place outside the city until the national army prevailed.

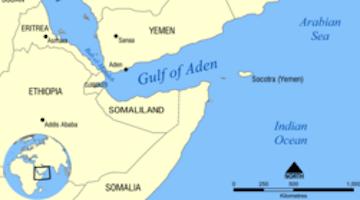

A Chinese firm had been paving roads in and out of Lalibela and beyond but the TPLF drove them away, stole all their equipment, and occupied their base. I was loving the Chinese whenever we were riding on the sections of the road they had paved, and cursing the TPLF whenever we were bouncing up and down on gravel roads including all sorts of hazards.

Hotels abound in Lalibela since tourism is the sole industry of any significance. The TPLF looted and damaged many of them, leaving others owned by TPLF members or sympathizers in place. We were told that the TPLF had looted the hotel we stayed in, the Mezena, but that the computers and television screens had been replaced.

There was no electricity in Lalibela—unless you had a generator—because, we were told, the TPLF had blown up the substation in Alamata, a town further north, just across the border of Amhara and Tigray Regions. Hadn’t they shot their own foot by doing so? Jemal Countess said he thought so, but I wondered whether they hadn’t simply disabled the 285-mile high voltage transmission line that the Chinese had constructed to transport electricity from Alamata to Legetafo in central Ethiopia.

The Chinese are building roads and electricity infrastructure, the first steps toward development, while US policymakers sponsor the TPLF, who chased the Chinese off and incapacitated the electricity and thus the plumbing for nine poor towns. Sometimes I think that Samantha Power, Antony Blinken, Susan Rice, and other US policymakers must have secret investments in China since they keep doing their best to push Ethiopia and other African nations into its arms.

We couldn’t travel to Alamata because it’s under TPLF control, but whatever they had done to the substation or the transmission line, there was no electricity for anyone without a generator in the nine cities south of Alamata on the road that goes in and out of Lalibela. The hotel we stayed in has a generator that they turn on from 7 pm to 10 pm, so that guests can enjoy the evening and charge their electronic devices. They only do so, however, if there are enough guests to justify the fuel expense, so we were lucky that a dozen or so Spanish tourists arrived just as we did.

Because there was no electricity in Lalibela, there was no plumbing—again, unless you had a generator. Our hotel managed to keep the water flowing during the day, but hot water was available only for a few hours at night while the generator was also keeping the lights on.

Many families had one spigot in their homes vut those were now dry. Instead people lined up at water tanks with jerry cans or carried them to streams even though it’s the dry season so the water was very low.

We drove north of Lalibela—on those partially paved, partially gravel roads—to Sekota to see the three IDP camps there. Along the way we were stopped at several checkpoints where national army soldiers asked for our passports. Just past the entrance to Sekota, we passed a college now serving as an area command base for the national army. Jemal said we were near the front line, but we didn’t see any fighting.

From there we drove on to three IDP camps populated by Amhara IDPs who had fled their homes very near Amhara Region’s northern border with Tigray. One after another told us that the TPLF had taken everything they had until they finally fled for their lives. In the first camp there wasn’t nearly enough water or food and people were cooking on open fires inside large tents delivered by the UNHCR, some of which were sheltering a hundred or more people. Some people did have thin mattresses to sleep on. If there were any sanitation facilities besides the open space surrounding the camp we didn’t see them.

The second IDP camp was even worse, with hundreds of people all gathered in one tent, sleeping on the floor without mattresses. Food and water was again in short supply, some people looked desperately thin, and those with food to cook were doing so on open fires where they lived. We talked to one young woman who said she wanted peace, she wanted to go home to whatever was left there, but if she couldn’t do that, she wanted to put on a uniform and fight with the national army.

The third camp, on the edge of Sekota, was even worse, with hundreds of people living under the most rudimentary shelters, tarps stretched overhead but without sides. Again, food and water was scarce, and people were cooking on open fires in the same space they lived in, and here, animals mingled with people and it was evident that there were no sanitation facilities.

As much as I hate the pattern of US proxy wars with all the big NGO businesses following in their wake, I couldn’t leave such misery without hoping that the UN and NGOs would arrive soon and/or do more for these people. Better yet, the government, but the government has twice declared unilateral ceasefires that the TPLF has not respected, so its resources continue to be drained by the war.

The surgical strike

My last observation about Lalibela and the surrounding region for now is that we went to visit the site of a surgical strike that ended the TPLF occupation. I have to admit that I’ve never thought such a thing was possible, but the Ethiopian national army hit the hotel taken over by the top TPLF officers with a drone strike that destroyed the hotel and killed the officers without damaging the rest of the community, and that was the end of the occupation.

The site wasn’t pretty. There were large bloodstains left where officers had died in pools of blood and the hotel walls were pocked with pellet-sized indentations that suggested the use of anti-personnel weapons. However, this strike ended the occupation and freed the people of Lalibela. And it belied accusations that the national army is just drone bombing indiscriminately.

More to come next week.

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at ann(at)anngarrison.com.