“We forget easily in America. We have forgotten the story of the Palmer Raids.”

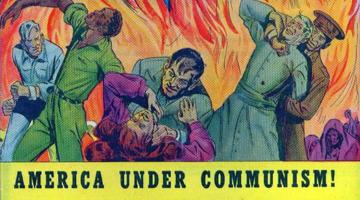

In 1948, at the beginning of the Second Red Scare, that period of anti-radical terror, repression, and persecution that arose in the United States after World War II, the Labor Research Association prepared a pamphlet on the First Red Scare, that period of anti-communist hysteria, repression, and persecution that arose in the United States after World War I.

Their pamphlet was titled The Palmer Raids, its name taken from the figure who initiated the First Red Scare: U.S. Attorney General and presidential hopeful A. Mitchell Palmer. In November 1919 and January 1920, Palmer, via the US Department of Justice’s newly-formed General Intelligence Division (which later became the Federal Bureau of Investigation, under chief investigator J. Edgar Hoover), oversaw a nation-wide purge of anarchists, communists, immigrants, and workers. The Palmer Raids were marked by rampant police beatings, the arrest and detention of ten thousand people across thirty-six cities, and the deportation of more than 500 immigrants, all of whom had been accused of harboring radical, anti-American tendencies.

For the Labor Research Association, the Palmer Raids were not merely a footnote in the United States’ past. The Raids were a sign of the country’s future — and of the ease with which the US could swiftly return to fascism. Indeed, at the time of publication in the late 1940s, editor Robert W. Dunn noted the “deportation delirium” gripping the United States, as seen in the deportation of Black immigrants Ferdinand Smith and Claudia Jones, among many others. Dunn also commented on the “illegal and unconstitutional” tactics used by J. Edgar Hoover and then Attorney General Tom C. Clark at the start of the Second Red Scare – as well as their attempts to weaponize the law against U.S. citizens.

In The Palmer Raids, the Labor Research Association meticulously documented how these tactics emerged, how the law was weaponized, and how the anti-radical terror and repression — beatings, detentions, and deportations – were unleashed alongside the foul state-sponsored spewing of racist, anti-immigrant hysteria. It does not, of course, take much to see the same tactics currently being used by United States Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem and former Border Patrol "commander-at-large" Dan Bovino in Minnesota, and elsewhere across the United States. For this reason, it is worth returning to the Labor Research Association pamphlet, The Palmer Raids. We provide an excerpt below.

The Palmer Raids

Labor Research Association

Eternal vigilance, they say, is the price of liberty.

Then they say, it can’t happen here; America isn’t Germany.

We forget easily in America.

We have forgotten the story of the Palmer Raids.

They did happen here, and not so long ago at that. A lot of the people who were mixed up in that affair are still around: J. Edgar Hoover, for example, who is now head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Six thousand innocent persons seized, arrested, and thrown into jail, in one night, is a pretty big job. And when the victims are chosen because they happen to be active trade unionists, or members of certain political parties and minority groups, you can transform a free country into a despotic police state, if you can get away with a stunt like that.

Yet that was the job pulled off on the night of January 2, 1920, by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his right-hand man J. Edgar Hoover. And it happened here.

This is how it happened.

THE DEPORTATION ACT

First Congress passed a law: The Deportation Act of October 16, 1918. This act provided for deportation of aliens [i.e. foreigners] who are anarchists, that is to say, persons who do not believe in any form of organized government, and of aliens who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the United States government or who are members of any organization that advocates the overthrow of government by force.

Of course, sometimes a law works out peculiarly. Take, for example, the Espionage Act of 1917 and its amendment known as the Sedition Act of 1918. Not one bona fide spy was ever tried under this law. But eight hundred and seventy-seven citizens were convicted under this law from June 30, 1917, to June 30, 1919, without one proven act of injury to the military services.

Eugene Victor Debs, whom nearly a million voters wanted for President, went to jail under this law. The Socialist Victor L. Berger of Wisconsin was excluded from his seat in Congress because of a conviction under this act, a flimsy conviction later reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court. Under this law the freedom of the press was trampled on, and newspapers like the New York Call and the Milwaukee Leader were barred from the mails.

Now see what happened with this 1918 Deportation Act. Although it was worded against “aliens” and “anarchists,” it was brandished at once as a weapon of propaganda against “reds” — as every a rather general and loose term. On January 8, 1919, the New York World headlined on page one:

Meet “Red” Peril Here with a Plan to Deport Aliens

The subhead ran: “All Bolshevists in America Being Listed by Departments of Labor and Justice.”

Next it was used, but not against “Reds” and not against anarchists. It was used against militant trade unionists and foreign-born workers. On Lincoln’s Birthday, 1919, fifty-four members of the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) were ordered deported.

But the war had ended. Opposition to such anti-labor tactics was growing. For their part the workers had borne the brunt of the war and were not ready to submit tamely when a business organ announced: “Wartime wages must be liquidated.” Having learned the worth of trade unions, they were not willing to give them up even in the face of a powerful open shop offensive by employers. In 1919 more millions of workers went on strike than ever before in our history to win union recognition, to improve their hours and pay. Great struggles occurred in steel and stockyards, in coal, textiles, and clothing, a general strike in Seattle, even a police strike in Boston.

On the employers’ side of the fence no holds were barred in resisting every effort of the workingmen to win their legitimate demands. It was the heyday of the blacklist and the paid strike-breaker, of injunctions and anti-labor violence. Here the usefulness of the Deportation Act was most clear. It could serve to divide the workers themselves, to raise a fever heat against the foreign-born, to paralyze the most militant.

The Department of Labor was then the authority which had responsibility for deportations. It moved, but it could not move fast enough to satisfy certain interested parties. Something was needed to scare the public, to whip up hysteria.

Something was provided.

Excerpted from Labor Research Associates, The Palmer Raids, Robert W. Dunn, editor (New York: International Publishers, 1948).