Contemporary conversations about racism in Cuba appear to have forgotten what it was like for Africans on the island republic before the Revolution. Afro-Cuban architect and journalist Gustavo E. Urrutia provides a stark historical reminder.

Recent discussions of racism and anti-Blackness in Cuba, and on the experiences (lived or otherwise) of Afro-Cubans, have been notable for a certain historical amnesia. The long history of racism in Cuba and of the subordinate status of African people in the island republic before 1959 have somehow been forgotten -- erased, even. Racism in Cuba is cast as being of recent vintage, a product, somehow, of the Cuban Revolution itself.

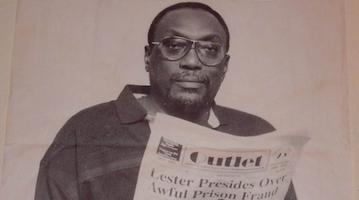

In light of this historical amnesia, it is worth revisiting the work of Gustavo E. Urrutia. Urrutia was one of the most important and influential writers on racism, African culture, and Black citizenship in pre-Revolutionary Cuba. Born in 1881 into a free Black family in Havana, Urrutia trained as an architect but made a career as a journalist. He was invited by the editor of the Havana newspaper Diario de la Marina -- a conservative journal founded in 1844 that, historically, had been the mouthpiece of Cuba’s planter class -- to contribute to their Sunday supplement. Urrutia was given a page that he titled “Ideales de una raza,” where he advocated for the equality of rights of, and opportunities for, Black Cubans, and created a platform that celebrated African culture in Cuba. Poet Nicolás Guillén, for instance, was “discovered” by Urrutia and Guillén’s ground-breaking poems from Motivos de Son with his use of African syntax and rhythms, were first serialized in “Ideales de una raza.” Urrutia, who counted both Langston Hughes and Arturo Schomburg as compadres, also wrote extensively on Black America; commentaries on Hughes, W.E. B. Du Bois, Mary McLeod Bethune, Booker Williams, the Scottsboro boys, and the architect Paul Williams all appeared in “Ideales de una raza.”

While Urrutia continued to write for Diaro de la Marina until the 1950s, “Ideales de una Raza” only ran from 1928 to 1931. These were years of tumult and turmoil in Cuban society: the price of sugar was at a historic low, the economy was tanking, the republic was heavily indebted to Wall Street, and the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado y Morales (a figure Julo Antonio Mella dubbed the “Mussolini Tropical”) was brutally suppressing radicals of all stripes. Blackness and the African roots of Cuban culture occupied a difficult, ambivalent place in Cuba society during this period. On one hand, Afro-Cubans, alongside Haitian and Jamaican immigrants, were blamed for the island republic’s economic and social problems. On the other hand, Afro-Cuban culture was increasingly embraced as the soul of the Cuban nation while being celebrated as an antidote, to use novelist Alejo Carpentier’s phrase, to Wall Street and the grip of US imperialism on the island.

Reproduced below, Urrutia’s essay “Racial Prejudice in Cuba: How it Compares with that of the North Americans,” was written in 1932. It provides a compelling, nuanced, and ultimately disturbing reading of racism and Black citizenship in Cuban society. Striking and blunt, Urrutia compares the history of racism in Cuba to that of the United States while also showing both the regional particularities of Cuban racism, and the impact of Spanish, French, and US racist thought and practice on the island. Not merely diagnostic, Urrutia argues that a social revolution is necessary for the elimination of racism in Cuba -- but he also warns of a genocidal future for Cuba’s Black population. The essay is by no means perfect. Urrutia surprisingly lauds the work of the US in Liberia. One wishes he had written of the Cuban “Race War” of 1912 that saw Black veterans of the independence struggle lynched in the streets of Havana after launching an independent, Black political party. What are Urrutia’s thoughts on the anti-immigrant (that is, anti-Haitian) sentiment that emerged in the twenties and thirties, often finding expression in the writings of Ramiro Guerra y Sánchez, Urrutia’s fellow columnist in Diario de la Marina? And of course, one wonders how Urrutia would view the Revolution itself.

Urrutia died in 1958, the year before Fidel Castro seized power and the Revolution triumphed. Commenting on Urrutia’s writing in a 1943 essay for Phylon, African American scholar Mercer Cook asserted that “Sociologically, historically, and stylistically, [Urrutia’s articles] which, unfortunately, have not yet been published in book form, constitute the most complete and interesting document available on the race question in Cuba.” Urrutia’s “Racial Prejudice in Cuba” supports Cook’s claim. It is also a powerful testament against historical amnesia.

Racial Prejudice in Cuba: How it Compares with that of the Americans, 1932

Gustavo E. Urrutia

Despite the proximity of the island of Cuba to the southern coast of the United Sates despite the positive, assimilating influence of Uncle Sam over Liberia, and despite the fact that in both countries Negroes and their descendants lived in slavery until the second half of the nineteenth century, there is a distinct difference between the racial prejudice of North American whites and that of Cuban whites with regard to the colored people. In the United States the white race strives to isolate the Negroes and segregate them in every possible way. The Anglo-American considers his Negrophobia as a natural and legitimate sentiment, and he gives expression to it frankly. For the Spanish Cubans it is a shameful sentiment which they will not on any account confess to the Negroes. They try to dissolve the black race in a torrent of Aryan blood, and aim at their extinction in every possible indirect way. The ultimate aim in both cases is to exterminate the Negroes.

These differences between the anti-Negro policy of the gigantic republic of the north and that of our diminutive Cuban public may be traced, I believe, to the historical difference between the spirit of English colonization in the United States and that of Spanish colonization in the Great Antilles and a large part of America. They are the consequences of the distinctive civilization and character of the British and the Iberians.

The English conception of colonization was exclusivist, while the Spanish had the idea of fusion. Ethnic caste, “purity of blood,” is a British and Anglo-American fad, while for the Spaniards and their colonial descendants there was no special advantage in paying careful attention to genealogy. The English pilgrims brought with them to North America their wives and families, together with all their customs and traditional virtues and vices, and in order to defend them and maintain the purity of their race they pursued, persecuted and exterminated the aboriginal Indians.

On the other hand, the Spanish colonists were men who came alone, without their families, and had need of the native women. They subdued the native peoples and used them to develop the wealth of the colony, and, with this object in view, instead of persecuting and suppressing them, they needed to live with them and join with them in order to found their American empire. When Indians suffered death at the hands of Spaniards it was not as enemies but as slaves.

II

These were the contrasting ethnic and social conditions with which African slaves had to contend in North American and in Cuba. These were the conditions which operated during their prolonged slavery, and which, today, supply the motives for the conduct of North American whites toward their black fellow-citizens, and that of Cuban whites towards theirs.

After a long colonial period, both countries revolted against their respective home-countries and finally obtained political independence. For this, Cuba is largely indebted to her Negro population on account of its heroic collaboration. In both cases democratic constitutions were adopted and the principle of equality for the Negroes in their civil and political rights was recognized. Social and economic equality is not prescribed for anybody in any country organized on aristocratic or bourgeois lines because in such countries neither does this equality exist nor do the ruling classes wish it to exist. It is precisely this social and economic inequality which serves as a stimulus to rouse all the proletarian masses against the present capitalist regime and which will eventually bring about its downfall everywhere. In countries were there is an anti-Negro prejudice, such as the United States and Cuba, the sufferings common to all the lower classes ostracized socially and economically becomes greatly accentuated in the case of the belonging to the black race. However great may be the merits of Negroes, considered either individually or collectively, they are always belittled by the accident of their race. It is the Negroes, therefore, who should look forward with the greatest impatience to the establishment of a universal regime of equality for all classes.

It was, nevertheless, under distinctly different conditions that the American Negroes and the Cuban Negroes acquired the civil and political rights guaranteed by the constitutions of their respective countries. The Negroes of the United States have stolen a march over those of Cuba in the enjoyment of liberty, but certainly not in their contribution to the struggle for the independence of their country. Here again, much is due to the difference in character, already mentioned, between the white men of Cuba and those of North America.

The United States became independent of England in 1783, thanks to the courage of the white colonies. The collaboration of the Negroes was slight though heroic, because the descendants of the English did not make any concessions to their slaves with the object of getting their help in the winning of independence. On account of their pride, the co-operation of a supposedly inferior race perhaps appeared humiliating to them. This republic kept the Negroes in slavery until the year 1865. Then it had to amend its constitution so as to grant them equal civil and political rights. But even in 1932 there are some States in the American Union which, by means of legal subterfuges, cheat the Negroes of these rights.

In Cuba slavery was abolished before the political independence of the country was obtained. When, in the year 1868, the white patriots began the first effective revolt against Spanish domination, they commenced by granting liberty to all slaves who wished to join the revolutionary army, and, in the name of the future republic, conceded to them the civil and religious rights of democracy, accepting them as allies with perfectly equal rights and duties. Owing to their intelligence and their bravery, the Negroes, together with their white compatriots, occupied all the ranks of military hierarchy from privates to generals in command of troops composed of men of both races, with no discrimination of any kind.

When, by means of a peace treaty with Spain, this Ten Years War (1868-1978) was ended, the white patriots demanded that the Spanish Government should recognize the liberty of the Negro revolutionaries. The non-combatant Negoes in Cuba remained slaves until 1886, when, at the instigation of the white separatists of Cuba, and of many Spanish abolitionists, Spain entirely abolished slavery in Cuba.

From the beginning of the Ten Years War until independence was obtained as a result of the final war (1895-98) there existed a perfect community of ideals, aspirations and suffering between white and Negro separatists. But amongst the supporters of the colonial government matters were quite different. They still maintained the racial prejudices of the slave tradition.

III

Ah, but once the Cuban Republic was established, those white revolutionaries, who had shown such sympathy for their coloured brethren, while they needed them in order to fight against the Spanish army, now became just as studiously opposed to them as the pro-Spanish Cubans. With the Republic they founded a cold democracy, soulless and blind, which has apparently fulfilled all the democratic privileges of the Revolution. Article 11 of our constitution even says: “All Cubans are equal before the law. The Republic recognizes no personal jurisdictions or privileges.”

This is true. For the Cuban State all citizens are equal. It sees no difference between a white man and a Negro. But neither does it see the subtle distinctions which are made in spite of the law against Cuban Negroes, not from racial but from color motives, as we shall explain later.

In the public life of Cuba there is no official and ostensible discrimination against coloured people. There is no separation of whites and blacks in public education, in the army and the navy, in the police, in public employment, in legislative or executive matters, in judicial employment, nor in the recording of votes. In an electoral meeting, Negores and whites, the learned and the illiterate, rich and poor, all have the same power. Nor is there any racial or color distinction in matters of public charity. There are no special hospitals for whites and others for Negroes, no railway carriages exclusively reserved for Negroes, nor are there special districts for Negores and whites in the cities.

As long as slavery lasted all these colour distinctions existed. After its abolition many of them remained, until the republic was established. During the republican period all these distinctions are illegal, they are accepted without question in many parts of the United States. In our official sphere nobody attempts to revive them, and the law is on the side of anyone who pleads against any attempted exclusion, on the ground of race or color, in the activities of private life.

But here we have the subtle and delicate part of the racial problem of Cuba. In private circles, and even in public life, anti-Negro prejudice finds its expression, not in open discriminations, as in the United States, but in a quiet and surreptitious way. The Negro is not excluded, but some pretext is always found for not accepting him. He is not hated, but neither is he loved. He is not killed, he is not lynchched, but he is left to die of starvation. The Negro population is not concentrated and driven away to a “black belt” where it may perish through poor living conditions but it is continually crossed with the white race, in order that it may become extinct. The object is not that the Negro may, through his exclusivism develop his own ethnic spirit, as in North America, but rather that his soul may be poisoned by a torturing infinity-complex and a suicidal desire to escape from his own race.

This interminable series of contrasts between extreme anti-Negro sentiment in North America and the shades of Cuban disaffection may be traced to the original and profound difference between British exclusivism and Iberian fusionism, inherited respectively from the Anglo-Americans and the Spanish Cubans. The North American is more or less resigned to seeing the Negro; what he affirms he will not tolerate is to feel the Negro in his blood, or to have intimate relations with the black race. On the contrary the Cuban white man is not averse to feeling Negro blood in his veins, but he denies Negro relationships and is a party to a conspiracy to banish the black color from Cbuan ethnography. His ambition is that our country shall be one of light yellow-skinned half-castes who are to be called “whites.” In my opinion this will take place in much less than a century, but I hope that by that time our mentality will have progressed sufficiently for us to attribute no importance to peoples color, race, nationality or religion.

It is proverbial that in the United States one drop of African blood makes a white man a Negro. In Cuba the reverse is the case. On drop of European blood makes a Negro a white man; so much so that in colonial times a large number of half-breeds, more or less chocolate in color, were white men de jure and enjoyed all the privilege of the white race, being inscribed as white on the official registers.

In Cuba a pro-white policy is carried out in all national activities, and one of the methods of this policy is to enroll half-castes as whites in the census reports and other demographic registers. In the last report published — that of 1919— the total population was given as 2,889,004, divided by race as follows:

Whites

Foreigners 272, 030

Cubans 1,816,017

Coloured people:

Negroes 323,117

Half-castes 461,694

Yellow people (Chinese) 16,146

Total: 2,889004

But the number of really white Cubans is very small, and is almost indeterminable. The rest of those who are coined as whites are not so, either in colour or in race.

In the year 1931 a new census took place, which indicated a population of 3, 670,000. The result have not yet been published, but from a racial point of view we may assume that they will show the same proportions, apart from a reduction in the number of Negroes and an increase in that of whites and half-castes, due to a constant crossing of the two races and especially to faked enrollments.

IV

Our laws make for equality, but the men who rule the nation— white Cubans — are otherwise preoccupied, and they permit certain qualities within the margin of the law. In official employments, conferred by appointment, colored men share only in a small proportion which does not exceed 3 percent, despite the fact that they form 27 per cent of the total population of the island. There are no Negroes among the naval officers and not one in the aviation corps. However, in the high ranks of executive power we have had a Government Secretary (the most important position in the interior of the country, next to that of the President of the Republic). There have also been two Secretaries of Agriculture. The present Secretary of Communications is also a coloured man, as is also the Secretary of Justice. There are other important posts held by members of our race.

In elective posts we have had three seniors, one of whom was president of the senate. In the Chamber of Deputies there are always coloured legislators. At one time we had 14 representatives in the same legislature. Negroes also figure in other elective posts in the nation. The elections are not by races but by provinces and municipalities.

V

There exists a kind of unwritten law by which Negroes and whites unite for the needs of public life and separate for those of private life. This separation is rigorously observed in the social sphere. In the economical sphere there are occupations in which people of all colors work together, and others from which dark people are tacitly excluded.

The prejudice is not uniform in the six provinces which form the county. White men and the half castes who pass for white live together and have their own exclusive social circles. This is true, in general, of the whole island. In the eastern provinces of Pinar del Rio and Havana, and in the central province of Matanzs, there is no distinction between Negroes and half-cases. They form another social class and meet in their own circles. In this region there are two big groups: white men and coluured men. In the other central province, Santa Clara, and in the two eastern ones, Camaguey and Oriente, the coloured race is divided into three groups: a, Brown people, who consider the whites as superior and the blacks as inferior them them; b, Half-cases and Negroes who behave in the same way as those of Pinar del Rio, Havana and Matanzas; c, a third group composed entirely of Negroes, just as exclusive and as proud of their race as the brown people are of theirs. Groups a and c maintain circles (societies) where only those of their own color are to be found. In those of group b there meet all those who do not live as whites, being very light in color or very dark.

From the province of Santa Clara to that of Oriente there exists an acute social antagonism between group a and group c. This is due to the French colonists, expelled from Hayti by Dessalines. They took to this region and inculcated in their half-caste children a sentiment of superiority over the Negroes. In the provinces of Pinar del Rio, Havana and Matanzas, the purely Spanish fusionist tradition is maintained, and all those who do not figure as whites consider themselves Negroes. For this reason, I, who am from Havana, when I say “Negroes” refers to all those who do not count as whites, whether their skin be of ebony or of jazmin.

In certain places in the south of the United States, such as New Orleans, where also some of the French expelled from Hayti took refuge, a similar “aristocracy” of brown people is cultivated within the all embracing racial subordination of the black race; and we may even find some large cities in the north of that country whee the same vice is developed, perhaps by contagion — a vice equally unworthy there as in Cuba but more absurd in the land of jim-crowism, whee, although it is true that every year some five thousand half-castes “Pass” into the white race, they must needs except brutally fro this race even person in whom is detached the slightest trace of African blood. In our island white society stimulates and protects this shameful invasion.

Private schools and teaching institutes in our country do not generally admit colored pupils unless they can pass for white. Still, intellectual people, artists and professionals of both races have their place in cultural life, and are even accustomed to meeting in the same clubs connected with their specialities. But as soon as any celebration of a social character is organized, especially if it is a dance, all communication is tacitly interrupted.

VI

The economic control of Cuba is chiefly in the hands of foreigners: x, Spaniards, in business, in part of the tobacco industry and in the greater part of the secondary industries. These are the concerns of persons or companies resident in the country. y, North Americans, in part of the tobacco industry, banking, and the most powerful enterprises concerned with public services. All this is owned by limited liability companies resident in the United States. There is also a small proportion of merchants. z, Other foreigners: Englishmen (they have an old railway enterprise, with headquarters in London), Frenchmen, Germans, Chinese, etc.

The Cuban whites owned almost all the wealth of the island in the time of slavery, but they abandoned or destroyed it, or the Spanish government confiscated it during the long revolutionary period of the separatist wars, which took place between the years 1868 and 1898. Today the natives live by public works, and by a little participation in the sugar, tobacco and other industries by agriculture on a small scale, by secondary employments in commerce and industry and as workmen or manual laborers. At present they are beginning to learn the retail trade in foodstuffs.

In connection with the pauperism of the natives, the most destitute and indigenous class is that of the coloured race. While he lived in slavery, the work of the Negro was the basis of our economy. He was employed in agriculture, in municipal functions and in domestic service. Being destined, then, to conspire and fight for the independence of Cuba, for thirty years he was steadily losing these positions. After the establishment of the republic, the whites, believing that they had no more need of the Negro, and forgetting the advantages of national cohesion, openly pursued the policy of making Cuba a white man’s country. With this object in view, they encouraged the immigration on a page scale of Spanish workmen and others, who have managed to oust the Negro in almost every branch of work.

The Cuban Negro is not today such an indispensable factor in our economy as the American Negro is in that of the south and north of the United States. If the white Cuban lives precariously, the Negro becomes a perfect pauper, whom his white countrymen keep excluded, partly from motives or racial prejudice, and partly in order not to share with him the scanty means of living at the disposal of the native.

This tragic economical situation the Cuban Negro in his own country has become worse with the world-wide economic depression, and the sugar disaster provoked in Cuba principally by the furious tariff protectionism of President Hoover’s government.

Despite the essential difference between the anti-Negro tradition of the United States and that of Cuba, we feel more and more every day the influence of prejudice a l’americaine. The economic pressure of that country over ours counts for as much as he intellectual influence. In colonial days Cuban youths who preferred to study outside Cuba would go to European colleges and universities. They would visit Spain, France, Belgium or Germany, and from there they would come back free from prejudice against the Negro. But now that rich young men are educated in the land of Washington, they come back feeling even more enmity towards the Negoes than does the abominable Jim Crow.

VII

Such is the true aspect of racial prejudice in Cuba. Coloured people consider themselves defrauded because the promises of the Revolution were for real and cordial equality, and the white Cuban, who governs, does not practice this equality.

Of what use, then, are precepts of equality to the Negroes? Of what values are the written laws, when the person for whom they were designed lacks the power to have them enforced? The racial problem of the American Negro and that of the Cuban Negro, though dissimilar in form, is essentially the same: the social and economic subordination of both groups to the white race, and the danger of extinction. The North American kills the Negro. The Spanish Cuban leaves him to die.

But the Negro in America and in Africa is beginning to be no longer alone. His problem of life and death is the same as that of the other obscure races; the same as that of the proletarian masses of the world. And these suppressed races, these destitute multitudes are beginning to understand one another, to communicate with one another and to love one another. It is not now merely a local clash of races, but an immense question of human justice. It seems that we are approaching a new cycle of civilization which will now be cohesive and universal. The efforts of all just, equitable and intelligent men and women throughout the world must join to contribute toward the advent of this new era in history. And the Negroes, having no selfish traditions to defend, with souls purified by suffering, free from rancor and full of brotherly love, are in a splendid condition to labour for the great human community of the future.

Translated from the Spanish by V. Latorre Bara.

Gustavo E. Urrutia, “Racial Prejudice in Cuba: How it Compares with that of the North Americans,” in Negro Anthology, Nancy Cunard, editor (London, 1934).