(from left) Achieng Oneko, Jomo Kenyatta, Makhan Singh, and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. Photo courtesy: Amarjit Chandan Archive

Originally published in African Arguments

Despite the veneer of progress, what does a historical critique of East Africa’s capitalist beacon reveal?

Just four years after independence, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga published Not Yet Uhuru, a seminal political treatise of the new country. 60 years after independence, and 56 years after its publication, one might argue that nothing much has changed. As a nation, we find ourselves still grappling with the question of how Kenya became free with the greater portion of the arable land controlled by a handful of owners even as millions are squatters on their ancestral land.

Author and journalist Parselelo Kantai asserts that if Kenya were a crime novel the plot would revolve around land. Land has always been the central question in Kenya. Our militant freedom movement named itself the Kenya Land and Freedom army, looking to get back ithaka na wiyathi [land and freedom in the Kikuyu language] that had been taken from us by the Europeans. Even at the guillotine, KLFA freedom fighters died holding a clutchful of soil, and imploring, “We have gone, we have died and you have been left. Never let go of this land, for it is what we die for”. But after independence, the issue of land and its (re) distribution remained a vexed topic. The emerging postcolonial elite, in power precisely because it had collaborated with the British colonial authorities against the KLFA (whom the British called Mau Mau), replaced the settler as the dominant class amassing large tracts of land for itself at the expense of the country’s majority – in perfect fulfillment of Fanon’s warning about the national bourgeoisie. And while the land question is frequently swept under the carpet – not least because the children/benefactors of the post-colonial elite remain in power – it is clear that it is still unforgotten by many. Memory of this is evident in my grandmother casually telling me: “Aria monire matunda ma wiyathi ni aria mathomete, aingi mari ngati na ciana ciao, ti aria mari mutitu, na nikio itendaga kuigua mundu witainwo na nie agithakira mabuku!” (That those who enjoyed the fruits of independence are those who were educated many being home guards and their children, and not those who fought in the forest). As Dauti Kahura and Peter Lockwood argue, the recent invasion of the Kenyatta family’s expansive Northlands ranch was a reminder that that ‘the land question’ has not been forgotten.

This invasion, for all its symbolic reasons, was muddied by the fact that it may well have been instigated by the William Ruto/Rigathi Gachagua-led Kenya Kwanza ruling party as a warning to former president Uhuru Kenyatta for his tacit support of the mass protests his ally, opposition leader Raila Odinga had been orchestrating.

William Ruto, while not exactly from the landed gentry of his predecessor Uhuru Kenyatta, might have once been a desperate hustler, but that’s ancient history. Over the past 30 years, he has amassed a very tidy real estate portfolio: 15,000 acres in Laikipia; 2537 acres in Taita Taveta and 395 acres in TransMara. This is in addition to contested property that the president has been linked to, including 1,600 acres in Nairobi’s Ruai area; and the 100 acres in Eldoret he dubiously acquired in the melee of the 2007 post-election violence that he was forced to return to owner Adrian Muteshi in 2013.

These issues were conveniently suppressed in his populist 2022 election campaign narrative that presented him as a street hustler up against the oligarchs of the collaborator dynasties of the 1950s Emergency era and the emerging African political elite that had led the negotations for independence at Lancaster House. The dynasts had taken the reins of state at independence and had faithfully governed the plantation on behalf of London and Washington ever since.

In addition, Ruto had offered his services to former president Moi from his university days. As a member of Youth for KANU ’92 – the populist movement that campaigned for Moi during the first multiparty elections in 1992 – he was allegedly rewarded with a tract of land in Eldoret, which he is said to have sold, using the proceeds to purchase his first car.

This is a game as old as Kenya itself. When thinking of Ruto’s populist hustler narrative, I am reminded of JM Kariuki exposing the Kenyatta administration’s corrupt land redistribution policy, despite he himself being a big benefactor of the Settlement Fund Trustees, through which the post-independence flawed land redistribution programme was financed and administered. If JM’s tool to get away with a life unexamined was his charisma, Ruto’s has been his fervent religiosity.

Ownership of large tracts in Kenya has almost always been associated with membership in the political elite. This African elite almost always advances the neocolonial agenda of its masters while its own nyapara (headman) lord it over the peasantry. Like the settlers of the colonial era, they are quick to introduce what Fiona McKenzie called the colonising discourses of betterment, often imposed on small land owners, and in the case of conservation, communal lands for pastoralists.

It is there that we find the fate of Kenyan smallholder farmers in 2023, whose ability to self-manage is being undermined as they are forcefully integrated into global agribusiness value chains. In the last one year and eager to please the West, the William Ruto administration (see Ruto’s offer to the UN to lead the mission to Haiti) has initiated several attempts to undermine food sovereignty in the country starting with the lifting of the ban on GMOs in the country (an order that has since been suspended by the country’s High Court); a Livestock Bill that contains livestock breeding regulations that seek to “regulate” livestock inputs and products to make the industry more competitive as a potentially significant contributor to the country’s GDP. The Bill is notable for a provision to fine farmers who prepare feeds without a license – a Ksh 20,000 fine or a six-month jail-term. More recent is an Animal Production Professionals and Technicians Bill that contains a proposal to fine those who rear animals without a license – a Ksh 500,000 fine or six months imprisonment in lieu. One can hardly keep up; a year under Ruto has seen a stream of similar Bills, as the Kenya Kwanza administration implements an IMF-designed austerity shocks on a beleaguered populace.

It is no surprise that these neoliberal reforms come at a time when the African Union is putting the final touches on a draft protocol on intellectual property rights to the agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The draft protocol reinforces an intellectual property rights system on seeds that most African countries have already introduced under World Trade Organization rules. A primary target of these agricultural reforms imposed on smallholder farmers is their right to save, share, and cultivate seeds and crops according to personal and community needs. By allowing corporate property rights to undermine local seed sovereignty, these reforms transform African farming into the new frontier for global agribusiness and promote export-oriented monocultures and undermine resilience at a time of deepening climate disruption (even as these reforms are promoted as part of climate-smart agriculture).

Resistance against these policies has been swift. In November 2022, the Kenya Peasants League obtained an injunction against the lifting of the GMO ban. In March 2023, the Court of Appeal upheld the ban against a further challenge lodged by the Attorney-General. It is worth noting that the ban has complicated US-Kenya negotiations on a Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership (STIP) – the first of its kind for the US in Africa – through which the Biden administration intended to boost GMO agricultural exports into Kenya, and by extension, Africa via the AfCFTA. The Kenya Peasants League based its arguments on the UN Declaration of the Rights of Peasants specifically the Right to Participation as outlined in Article 10; the Right to Information under Article 11; the Right to Seeds under Article 19; and Cultural Rights and Traditional knowledge under Article 26.

Arkam Lodhi terms these reforms “neoliberal enclosures” which guide market-led agrarian reforms. These reforms, Lodhi argues, are predicated on the assumption that land is, strictly speaking, an economic resource that should be allocated in order to maximize the benefits that accrue from its ownership and control. But, as he writes, this exclusive emphasis on the character of land as an economic resource as practiced by neoliberals – they do so even as they do not deny its non-economic dimensions, but argue that it is not possible to build policy around said dimensions – remains faulty in the extreme. It is also upon this assumption that the “betterment” colonising policies I briefly mentioned earlier are built.

One of the features of colonialism in Kenya was the undermining of farmer’s autonomy. Farmers were forced to plant specific crops and even specific varieties of their native crops such as beans, which Claire Robertson documents in her journal article on beans and agricultural imperialism. In addition to such agricultural imperialism, natives were also subjected to environmental protection policies under the long-enduring colonial prejudice that they didn’t know how to take care of their land. Much like the “climate smart” practices aimed at betterment today, these policies, ranging from monocropping rather than intercropping, deep rather than minimum tillage, and “clean weeding” rather than leaving the stalks in the soil after harvesting to anchor the soil against the onslaught of torrential rains, were not really helpful. In fact, they were later recognized as instrumental to the loss of fertility.

Another home these “betterment” land-related policies have found is within Kenya’s conservation sector, itself an old instrument of native dispossession. The case for conservation in Kenya today reproduces colonial fantasies of vistas of un-peopled savannahs rolled out for the benefit of white tourists. Economic justifications that tourism brings in foreign exchange that contributes to balance of payments and more recently carbon-credits – a market-based solution to pollution – remains rooted in both colonial and laissez faire logic.

Refreshed to incorporate the demands of the climate emergency, carbon sequestration “services” locks up carbon within agricultural and conservation practices – and thereby unlocks opportunities for corporate capital in carbon markets, as Stanley Fink, one of its more prominent champions and a former hedge fund manager, explained to King Charles (then Prince) a few years ago when the latter was fundraising for his Rainforest Project.

The alienation of communal land to form conservancies whose biodiversity services can now be converted into carbon credit projects has been marred by controversies, leading some to call carbon credit schemes a form of “green colonialism”. Like with colonial-era environmentalist policies sold as improvement, the envisaged changes that arise within land demarcated for these projects has been sold to communities as an improvement to their traditional pastoralist practices. Take the Northern Rangelands Trust project piloted among the Borana, a pastoralist community in northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia. The NRT’s arguments against traditional ‘unplanned grazing’ are not supported by empirical evidence, and indeed the project ignores that the ‘unplanned grazing’ is in fact subject to traditional forms of governance which have sustained pastoralism within broadly sustainable limits for many centuries, as a report by Survival International argues. We see, once again, environmental concerns being weaponised to legitimate security of title to the land and to persuade the (neo) colonial state to support a cause that has little do with conservation or the climate.

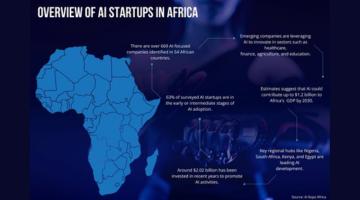

Why do we do this to ourselves? The problem is probably in our leaders’ acceptance of what Obeng-Odoom calls Conventional Wisdom. This belief in Conventional Wisdom is of course, a result of internalizing imperialist narratives about our beloved continent. In this conventional wisdom, Obeng-Odoom argues, Africa’s development has always been pegged on transnational corporations or state corporations acting as transnational corporations, parceling out Africa, the open pasture. The current version of this development vision, as Obeng-Odoom remarks, is that “The future is this frontier [Africa], this new land with opportunities and it is the business and the responsibility of maybe more enlightened Europeans, European interests to get into a kind of partnership… “. But we seem to forget, that “previous attempts at colonising the commons have been similarly framed with words such as “Protectorates”, “collaborators”, and “co-producers” being used as a veil for these processes”.

Last week, President William Ruto published a joint op-ed with Sultan Ahmed-Al-Jaber in the Guardian whose lede reads “As Cop28 gets under way, it is vital that corporations and richer nations invest in the global South”. And somewhere in the body of the op-ed is a paragraph that reads that countries do not confront the climate battle encumbered by debt, in essence with one hand tied behind their backs. Making adequate levels of financing available to all by releasing the full force of the private sector will re-ignite collective global green industrialization and support, and accelerate the drive to net zero and create jobs and prosperity.” Conventional wisdom. Non-African powers to the rescue, in the quest for African development.

We have borne witness to what the full force of the private sector and even institutions such as the monarchy have done to the commons in Africa, be it through colonisation or the current conservation lie to use the language of conservationists Mordecai Ogada and John Mbaria. But despite the documentation of these failures by scholars, and even the rejection of these visions by Kenyans whether through the Kamba people who resisted colonial livestock control in the name of erosion-control practices in 1938, the Murang’a women who refused to participate in the “betterment” of their land through communal terracing in 1947, the KLFA who took arms to reclaim their land in the 1950s, or the Maragua women who in the 1980s rejected the World Bank led visions of “development” that prioritized coffee at the expense of their own subsistence crop, these visions of the development of our land, and the place of our imperial masters in it endure.

Wairimu Gathimba is a writer and cultural worker within Kenya's social justice movement.