“We need to give greater theoretical centrality to the fact that European conquest of the world has established what is in effect: global white supremacy.”

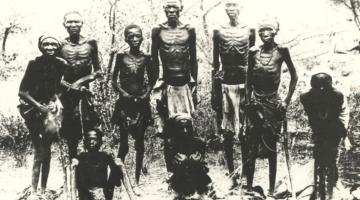

“White supremacy” is too often seen as an isolated, extremist phenomenon. It is viewed as the province of the far-right—of Kluxers and cross-burners, Afrikaners and apartheid, Trumpers and lynchers—of individuals and groups far outside the respectable norms of contemporary Western society and politics. Yet to view white supremacy in such a fashion is to miss two points. First, white supremacy is not an extreme ideology but a normative, everyday system of beliefs and practices in the modern world. Second, white supremacy is global. That is, white supremacy is not characterized by its formation in historically isolated, insular geographies — such as the US South or Apartheid South Africa. Instead, white supremacy emerged with European colonialism, the European construction of racial difference, the diffusion of racial whiteness as the epitome of humanity and civilization, and non-whiteness as inferior, and most importantly, the development of global political, economic, and cultural institutions that center white power. To miss these points is to have a mistaken view of the past five hundred years. It is a failure to understand how widespread conscious and unconscious ideas of presumed white superiority are normalized. It is the inability to see how relations of white dominance are practiced through countless institutions around the world.

In effect, we cannot understand the modern world without understanding how entrenched white power is in all our institutions. But to understand the source of that power, we need to recognize the significance of the European construction of race. Europeans constructed the idea of race as a hierarchical relation with the race “white” on top of the world and therefore deserving of the world’s power and control. This ordering shapes both our history and the current historical moment of extreme violence and terrible abjection. It makes sense, then, that all major “global” institutions — United Nations, International Court of Justice, International Criminal Court, etc — are fully controlled by those racialized-as-white with power conferred through a long history of conquest and genocide. It also makes sense that whiteness continues to have value (and power) even in majority non-white societies, where proximity to whiteness or access to white cultural accouterments represent value.

It is also important to note that an analysis of race is absent in many leftist formations. Jamaican philosopher Charles W. Mills challenged this absence head-on, arguing that “conventional assumptions of white radical theory radical theory,” especially Marxist theory, are such that “classes” of people are abstract and colorless.

Writing in an essay titled, “Rethinking Race, Rethinking Class,” published in 1995 in the journal Third World Viewpoint, Mills makes the basic point that it is impossible to understand the modern world without beginning from the historical fact of European racialized conquest and domination of the globe through the establishment of global white supremacy. Mills pointed specifically to the inadequacy of a Marxism with a “colorless” view of class and capitalism. Mills does not abide by the tired dualism of “race vs class;’” he does not see their separation or opposition. Instead, Mills argues for a “dual systems” approach whereby class is determined by race, and capitalism is shaped by racism. And race, for Mills, is social, not biological, but nonetheless very real in its effects.

Most importantly, Mills argues that to take global white supremacy seriously would force us to not only understand the economic importance of Africa and the Global South in the rise of Europe, but also to the structuring of “whiteness” (and those racialized-as-white) as power. Understanding “global white supremacy,” in other words, is critical to any left political and theoretical formation.

In some ways, Mills’ use of “global white supremacy” is drawn from Malcolm X. In 1963, Malcolm spoke about the global domination of white supremacy, but also of its end:

You and I were born at this turning point on history; we are witnessing the fulfillment of prophecy. Our present generation is witnessing the end of colonialism, Europeanism, Westernism, or "White-ism"...the end of white supremacy, the end of the evil white man's unjust rule. I must repeat: The end of the world only means the end of a certain "power." The end of colonialism ends the world (or power) of the colonizer. The end of Europeanism ends the world (or power) of the European...and the end of "White-ism" ends the world (or power) of THE WHITE MAN.

Malcolm saw in the Black and Third World revolutions sweeping the planet — in the increase of “the independence and power of the dark world’’ — the portends of global white supremacy’s collapse and end. However, the end of global white supremacy did not come in Malcolm’s time, nor in Mills’. But it may be coming in ours as the US, NATO, and its proxies in eastern Europe and West Asia — and the zionist entity desperately mounting white supremacy’s last stand – try to hold on to a world that is no longer theirs.

We may see the end of global white supremacy in our time. Global white supremacy might also lead to the end of the world.

Charles W. Mills’ “Rethinking Race, Rethinking Class” is reproduced below.

Rethinking Race, Rethinking Class

Charles W. Mills

The global disarray of the contemporary left has at least one great virtue: The chastened mood and self-questioning posture create a more receptive atmosphere for genuine dialogue around certain issues. Where so many official “lines” of various kinds have been so spectacularly discredited, it makes it easier to challenge some of the conventional assumptions of white radical theory. One such challenge, in my opinion, should certainly be mounted around the question of race.

Anyone who has ever done a standard introductory political philosophy course knows that mainstream theory has little or nothing to say about race. But in this respect at least, Marxism is part of the mainstream. That is, while being an oppositional body of theory within Western political thought, it is simultaneously very much a part of the Western tradition, sharing many of its critical assumptions about the political universe. Liberalism as a world outlook (in the broad, overarching sense that includes “conservatives” as well as “liberals”) posits a universe of abstract, colorless individuals. Marxism challenges this by insisting that these individuals are actually members of classes. But the classes themselves remain abstract, colorless classes. Thus, in neither case is race taken seriously.

The consequences will be familiar to any person of color who has ever tried to apply white left theory to their own lives and culture. Marxist categories are useful for capturing some realities, but handle others awkwardly and are completely useless for others. Yet as a supposedly comprehensive conceptual array, Marxism’s standard categories–base, superstructure, forces of productions, relations of production, class, bourgeoisie, proletariat, class struggle, value, commodity, alienation, etc.-- just can’t do the job of mapping the whole political universe.

Once one throws off the spell of Marxism as the globalizing theory, it should be appreciated that there is nothing really surprising about this. Social reality is complex, multi-dimensional, and not completely transparent from any single perspective. Instead, one needs to integrate conceptual insights from a number of different standpoints.

We also need to give theoretical centrality to the fact of the European conquest of the rest of the world, and to begin to see it as having established what is in effect a political system in its own right: global white supremacy. Only in this way can we do justice to the way in which race shaped the planet’s recent history.

I don’t see this as being tied exclusively to a left political perspective. In fact, it would be unfortunate if the notion were embraced only by the political left. There need not be ideological consensus on the origins and solutions for eliminating global white supremacy, but, like “patriarchy,” this should be seen as a broad umbrella concept about which people can agree, and in opposition to which people of different political orientations can then link up in principled alliances, join in cooperative theoretical mappings, and engage in debate over diagnoses and recommendations. The crucial idea is really to start conceptualizing racial oppression in a systematic theoretical way.

So beyond the minimalist–but crucial–theoretical commitment, there will necessarily be areas of disagreement as well as areas of agreement. But all people of good faith, regardless of race, should be able to agree that white supremacy is wrong and should be eliminated. As such, this is different from the debates around capitalism. With capitalism, there is no controversy on the factual question (whether or not it exists), but rather on the normative question (whether or not it is good or bad, just or exploitative). Here, by contrast, there is no controversy–except for racists–on the normative question (most people would agree that white supremacy is bad, unjust) debate revolves around the factual question (whether or not white supremacy still exists, how to fight it). For example, the mainstream of the U.S. Black liberation movement has not been anti-capitalist, but has traditionally sought a non-racist capitalism. A minority have argued for laissez-faire capitalism, seeing the free market itself as the solution to racism, while the majority have appealed for an active interventionist state. But the common assumption has been that white supremacy is largely detachable from capitalism. Others in the Black left tradition have taken a more radical view, arguing that white supremacy cannot be ended under a capitalist society. But since socialism as a solution is hardly uncontroversial these days, there should at least be the possibility of an alliance against racism across these ideological lines. Some would argue that in the 21st century world about to dawn, the best one can hope for is a race-free capitalism.

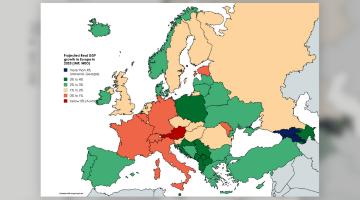

Taking the notion of “global white supremacy” seriously within First World left theory would entail at least two things. First of all–a fairly familiar criticism by now–it would have to be realized that standard internist accounts of the rise of capitalism in Europe are fundamentally deficient. From Eric Williams’ classic Capitalism and Slavery a half-century ago to more recent work of Walter Rodney, Samir AMin, Andre Gudner Frank, J.M. Blaut, and others, Third World and sympathetic First World scholars have argued that the role of colonial exploitation and African slavery was crucial in enabling the European “take-off.”

Unfortunately, this critique is still marginal to orthodox Marxist accounts, which merely give a left twist to standard Eurocentrism, making Europe a continent sui generis, uniquely destined to be the bear of historical progress and rationality. The “material” connections between the rise of Europe and the subjugation of the rest of the world and their legacy in the plight of the Third World today require greater emphasis.

The second implication is less familiar. I would argue that once one takes seriously the planetary shift in people’s moral standing precipitated by the European conquest, it becomes clear that the basic categories of Marxist theory–particularly those seeing humans as defined basically by their relation to the means of production–need modification and supplementation. Speaking of abstract raceless workers and capitalists is not theoretically adequate to the new social reality, because it fails to recognize the difference race now makes. One is dealing not just with capitalism; instead one is dealing with white-supremacist capitalism. Capitalism develops in conjunction with a system of global white supremacy in which Europe is the privileged continent, and Europeans are the privileged race. Two systems of domination are involved, not just one. And even if a case can be made that colonial capitalism creates global white supremacy, the system then develops an autonomy of its own which means that its workings can not just be reduced to class.

Those who remember the “socialist-feminsit” debates of the 1970s and 1980s will recognize the move I am trying to make here. Socialist feminists sought to develop a so-called “dual-systems theory,” which would synthesize the insights of radical feminists on gender and (male) Marxists on class by utilizing the concept of “capitalist patriarchy.” In other words, a concept that explicitly recognized that, on the one hand, existing capitalism was not gender-neutral, since women were allocated different social-economic roles than men, and on the other hand, that “patriarchy” was not an ahistorical essentialist structure, but something that evolved over time.

Because of intrinsic problems in this notion, the general decline in influence of left theory, and the rise of a postmodernism skeptical of all “grand narratives” and “foundational” theorizing, little has been heard of this project lately. But I think the model is still useful.

One cannot speak of “capitalism” in the abstract particularly in the economic systems implanted in the “New” World. Instead, one needs to see these as different forms of white-supremacist capitalism. So the generations of white Marxists in North America, and white and nonwhite Marxists in South and Central America and the Caribbean, who uncritically adopted Marx’s framework to describe these systems were, in a sense, mistaken. Once one recognizes that more than one system of domination is involved, and that they interact with each other, it should be obvious that the categories from Marx’s Capital will need modification.

The old cliched polarization of “race vs. class” is, therefore, in a sense misleading, since this formulation implies the clear separation, and necessary opposition, of the two. But once it is recognized that they are part of a dual system, it follows that both terms need to be rethought.

“Class” as a colorless Marxist abstraction defined simply by relationship to the means of production is theoretically inadequate, because classes in the New World will be defined by race. On the other hand, “race” is not a biological essence, but itself a categorization of one’s location in a system of oppression influenced by a materialist class dynamic. Abstract races do not exist, but racially categorized people interacting in a white-supremacist system articulated to an evolving capitalist economy that privileges some and disadvantages others.

A holistic understanding of the system is therefore not possible without paying attention to its racial dimension. In this respect, those who have been called “race men” in the Black American oppositional tradition have historically been correct in their insistence that the polity’s racial character is inadequately theorizable within orthodox Marxist categories. To write them off – as has standardly been done –as “Black nationalists,” “racial chauvinists,” etc., is to fail to recognize the blinkers on white political theory.

As pointed out at the start, white liberalism sees people as abstract individuals, for whom race is irrelevant. Focussing on the level of the juridico-political (e.g., dictatorship vs. democracy), liberalism misses the reality of economic class oppression. This reality is captured by the categories of Marxism, which sees people as members of classes in an antagonistic relationship with each other. But white Marxism itself has difficulty seeing other kinds of oppression since these classes are colorless.

Theorizing global white supremacy as a political system, on the other hand, makes explicit that whites in general, are privileged with respect to nonwhites. So although white workers are oppressed as workers, they are simultaneously privileged as whites, members of the “ruling race.” Certainly in the U.S., no adequate understanding of the development of workers’ consciousness and left movements is possible without recognizing this dual, contradictory location.

On the other hand, some Black nationalists and Afrocentrists can legitimately be critiqued for a biologically determinist and essentialist conception of race. The whole school of “melanin theory,” and the “ice people/sun people” absurdities adopted from white Canadian author Michael Bradley’s work, are examples of the mystification of race. These theories make white people intrinsically aggressive and exploitative. But the reality is that white people are constructed – not in the sense once expounded by the Nation of Islam (whites are created by the evil scientist Yacub), but in the sense that newborn infants of a certain genetic makeup are socialized into “becoming” white. “Whiteness” is not natural, but learned; one has to be taught the attitudes, values and behavior appropriate to a member of the master race. And, to their credit, there have always been “white renegades” who have recognized and repudiated this socialization.

So a “dual-systems” synthesis of this kind would be able to retrieve the insights of both the (white) left and Black oppositional tradition. On the one hand, it would recognize the existence of global white supremacy as a political system, thereby critiquing the colorlessness of orthodox Marxist theory. On the other hand, it would recognize the constructed nature of race, thereby critiquing the biological determinism of (some versions) of Black nationalism. Both the reality and the politicality of race would thus be explicitly acknowledged.

If left theory is ever going to be revived, it will need to confront its own historical deficiencies. The Eurocentrism of Marxism, blind to its own privileging of Europe and conceptually ignoring the theoretical significance of white domination of the planet, is one of the most important and damaging of these lacunae. What remains of the white left needs to start taking race much more seriously than it has ever done before.

Charles W. Mills, “Rethinking Race, Rethinking Class,” Third World Viewpoint 1 no. 4 (Summer 1995).