“To understand the history of the Americas we must pay tribute to…Haiti.”

August 22, 1791 marked the beginning of the Haitian Revolution, a 13-year war that would end with the establishment, on January 1, 1804, of the Republic of Haiti, the first free nation in the Western Hemisphere. Under the eventual leadership of African-born and formerly enslaved Toussaint Louverture, the Africans of Saint Domingue (as the French colony was called), rose up and defeated the white colonialists of the island, and then trounced not only the French army, but also the British, U.S. and Spanish forces. While Louverture was captured by Napoleon’s forces in 1803, the fight continued under Henry Christophe and Jean Jacques Dessalines. The Revolution upended the 300-year history of European enslavement of Africans and struck a dagger in the heart of colonialism and white supremacy.

But the founding of the Haitian state meant much more. The Haitian anthropologist, Michel-Rolph Trouillot reminds us that, “Haiti also stood alone as a country where national independence brought a change in the old order…the revolution changed the structure of the society, not just its relationship to a colonial power.” This is the unique character of the Haitian Revolution and why the free world is indebted to Haiti. Indeed, “to understand the history of the Americas we must pay tribute to the achievements of Haiti.”

While Haiti has suffered an unending white supremacist counter-revolution since it dared to be free, it is important to remember the significance of its Revolution for the region and the world. Trouillot does this well with his essay, reprinted below, on the impact of the Haitian Revolution on the Americas: “Haiti was the first country in the Americas where freedom meant freedom for everyone.” We should remember this – as Haiti and the region will be free again.

The Haitian Revolution and its Impact on the Americas

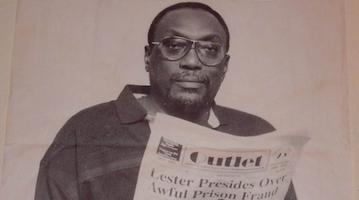

Michel-Rolph Trouillot

On July 14, 1789, the storming of the Bastille launched the French revolution. A year later, many white colonists in the French colony of Saint Domingue were worried about the news from France. Yet most did not doubt the “passivity” of their slaves. One colonist, a Monsieur La Barre, wrote reassuringly to his relatives in France:

I am telling you about our troubles here, so that misleading news does not trouble your mind. There is no movement among our Negroes. They are not even thinking about it. They are very quiet and submissive ... We sleep with our doors and windows open.

La Barre was wrong to sleep with his doors open. A year after he wrote the letter, the northern region of Saint Domingue was in flames, and 100,000 slaves had joined the revolution.

The Haitian revolution was the first and the most spectacular emergence of freedom in the Americas. It is the only case where the decisive action of the slaves themselves ended slavery. It is also the only case where the end of slavery brought with it the emergence of an independent nation with political power in the hands of the former slaves and their descendants.

In the late 18th century, Saint Domingue was the most profitable colony in the Americas. It was the world’s leading producer of sugar and coffee. The price was paid in human lives, by the slaves who worked on the plantations. So many slaves died from hard labor, illness and cruel treatment that the population could not maintain itself naturally. As a result, the slave owners had to constantly replenish the supply. Between 1764 and 1791, the French planters of Saint Domingue imported more than 300,000 slaves from Africa.

Not all of them accepted their fate. Many fled to the woods, becoming Maroons. Others, in smaller numbers, envisioned a total overthrow of the slave system, and attempted to poison the slave owners.

When the French revolution caused turmoil in France and its colonies, the slaves saw their chance. The uprising began on August 22, 1791. Within a few days most of the north of Saint Domingue was in revolt. Sugar plantations were destroyed, and hundreds of whites were killed or fled the island.

Two years of confusion followed, during which rebel slaves, planters, free blacks and French officials recovered from their shock and evaluated their forces. Spain and Britain took advantage of the situation to attack Saint Domingue, forging and breaking alliances with groups of rebels. The French government tried to salvage its colony by offering conditional freedom to the slaves. But it was too little, too late.

During those two years, a slave known as Toussaint Louverture had been formulating strategy and tactics. On August 29, 1793, he issued a call to arms:

I am Toussaint Louverture ... I have undertaken vengeance. I want liberty and equality to reign in Saint Domingue. Unite to us, brothers, and fight with us for the same cause.

From that point on, history became legend. Toussaint allied with the Spaniards to beat the French, then joined the French to beat the British. He expelled three white administrators, negotiated with the United States, and made himself general en chef, the de facto ruler of Saint Domingue. He also promulgated its first independent constitution.

Napoleon, who had just seized power in France, sent a formidable army to recapture Saint Domingue and restore slavery. Eighty-six warships carrying 22,000 soldiers from the best French regiments invaded the island. Toussaint’s forces were weakened, and he was treacherously kidnapped and exiled to France, where he died in captivity.

But freedom did not die with Toussaint.

The Black general is reported to have said after his capture, “In overthrowing me, the French have only cut the stem of the freedom tree in Saint Domingue. But the tree will grow again, so deep and strong are its roots.”

Indeed, the tree was not dead. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a former slave and follower of Toussaint, along with Henri Christophe, a free black, and Alexandre Petion, a mulatto, reorganized the revolutionary forces. The second phase of the war began in 1802. The French troops suffered defeat after defeat. At one point, Napoleon reportedly asked an officer who had just returned from the colony if a thousand new soldiers would enable France to restore slavery in Saint Domingue. The officer replied: “Not a thousand. Thousands ... thousands ... thousands ... and then, thousands again.”

In less than a year, the former slaves regained control of most of the colony. Dessalines led his army from victory to victory. On January 1, 1804, he proclaimed the independence of Haiti.

At the time of the Haitian revolution, slavery was widespread in the Americas. It existed from Canada to Chile, and was most important in the Caribbean colonies, the southern United States, and Brazil. It had survived as an institution for almost 300 years.

Although slavery was created for economic purposes and maintained through the use of violence, it also carried a mystique. The Haitian revolution broke this spell, proving that freedom could be won. Everywhere, slaves became more daring, slave owners more fearful. Slave revolts and conspiracies increased, in part because of Haiti’s example.

Migrants from Saint Domingue helped spread the message of freedom. During and after the revolutionary war, many Saint Domingue planters fled to the United States, sometimes taking their slaves with them. Many settled in the area which is now Louisiana, and in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk and Charleston. Others went to neighboring Caribbean territories including Guadeloupe, Martinique, Jamaica and Cuba.

In 1795 there were two major slave revolts in Cuba, and one each in Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Grenada and Venezuela. In Louisiana, the famous revolt of Pointe Coupee involved migrants from Saint Domingue. Afterwards, the state’s governor forbade further immigration of Blacks from Saint Domingue into Louisiana. The largest slave rebellion in U.S. history, which took place in Louisiana in 1811, was led by a man from Saint Domingue. And in Charleston, South Carolina, testimony at the trial that followed the Denmark Vesey conspiracy in 1822 showed the influence of the Haitian revolution on both slaves and planters.

These revolts and others helped bring about the eventual abolition of slavery in the Americas. Britain abolished the slave trade (but not slavery) in 1807. Holland was the first European country to abolish slavery in its American colonies, in 1818. Emancipation was proclaimed in British Guiana in 1827; in Mexico in 1829; and in the British Caribbean islands in 1834. In the Danish and French colonies abolition took place in 1848; in Colombia in 1851; in Venezuela in 1854; in Peru in 1860. The slaves in the United States were freed in 1865. Puerto Rico followed in 1873, Cuba in 1880. Brazil came last, in 1888.

In some cases Haiti, now ruled by former slaves, actively attempted to help others win freedom. The Haitian constitution of 1805 provided that any Black person stepping on Haitian soil became a free Haitian citizen, regardless of previous status and origins. Jean-Jacques Dessalines also called on African-Americans in the United States, both slave and free, to migrate to Haiti.

In 1822 the Haitians invaded neighboring Santo Domingo and freed the slaves there, a unique case of slaves being emancipated by former slaves. The Haitian government also helped Simon Bolivar in the wars to free the Latin American colonies from Spain. It did so in order to see slavery abolished in the liberated territories, although Bolivar did not always keep his promise of immediate abolition.

In many territories, abolition did not mean immediate freedom. In some places years passed between the emancipation proclamation and the actual freeing of the slaves. President Lincoln’s proclamation of January 1, 1863 had no enforceable effect on the status of American slaves until the end of the Civil War. In the British Caribbean colonies, abolition was followed by a four-year “apprenticeship” period during which the slaves were forced to continue working on the plantations.

One reason for this was that forces outside the plantation economies usually imposed abolition. Industrialists, humanitarians and government officials wanted to end the slave system, but they also wanted to protect the planters’ interests to a degree. In Haiti, by contrast, the most important abolitionists were the slaves themselves.

Haiti also stood alone as a country where national independence brought a change in the old order. In the United States, by contrast, once the colonists won independence from Britain, it was business as usual. Slaves remained slaves, property owners remained owners. The situation was similar in Latin America after the Spanish colonies broke free of Spain’s rule. But in Haiti, the revolution changed the structure of the society, not just its relationship to a colonial power.

The period from 1776 to 1843 is sometimes called the age of revolutions. It included the North American revolution, the French revolution, and the rise of the European and Latin American nation-states. But few historians have recognized the significance of the revolution in Saint Domingue. Indeed, many textbooks refer to it as a mere “rebellion” or “revolt.”

To understand the history of the Americas we must pay tribute to the achievements of Haiti. The French revolutionaries sought freedom, and the North American colonists sought independence, but the Haitian slaves won both. At a time when slavery went unchallenged elsewhere, and national independence placed control in the hands of rich property owners, Haiti was the first country in the Americas where freedom meant freedom for everyone.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “The Haitian Revolution and its Impact on the Americas,” published in Catherine A. Sunshine and Deborah Menkart, Eds. Caribbean Connections: Overview of Regional History. Classroom Resources for Secondary Schools, (Washington, DC Ecumenical Program on Central America and the Caribbean (EPICA), 1991). This essay was adapted from Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “The Haitian Revolution and its Impact on the Americas,” addressed to the Third World Plantation Conference, Lafayette, Louisiana, Oct. 27, 1989.