“Neither disaster, catastrophe, nor calamity can take precedence … over the color-caste system.”

The biblical flooding that afflicted the Bible Belt this past week — and, lest we forget, North Carolina but a year ago — serves as a reminder that, in an age of accelerated climate change, all natural disasters are in fact human-made. Unchecked growth in the name of profit has meant unparalleled destruction of the earth’s ecosystems. It has led to increasingly frequent, and increasingly extreme, weather events. The abject refusal to admit to the scientific facts of the climate apocalypse has intensified and accelerated the ecological catastrophe. So has the happy gutting of any U.S. governmental institution monitoring and responding to climate change – from the National Weather Service to FEMA to university laboratories. The result? Larger and larger populations in the U.S. (and across the world) have become more vulnerable to climate disasters, and less prepared to respond to the disasters as they arrive.

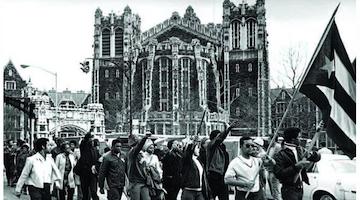

And of course, the most vulnerable populations are Black folk. While Black folk in the U.S. live in many of the places most susceptible to extreme weather and environmental disaster, we also are the least likely to receive state support to help us live through extreme weather and environmental disaster. We saw this in New Orleans in 2005 during Hurricane Katrina – and a century before Katrina, we saw this in Mississippi in 1927. Then, months of heavy rain led to devastating flooding, overwhelming and breaking the levees, leaving thousands dead and hundreds of thousands homeless across the Mississippi Valley. Relief efforts focused on whites – even though African Americans, in near slavery conditions, were conscripted for the labor of reconstructing the levees.

A 1927 Pittsburgh Courier editorial noted that, even though white self-interest should have meant that Blacks were afforded some relief, instead: “such was not the case. The whites of the Mississippi Valley ran true to form. Neither disaster, catastrophe nor calamity can take precedence there over the color-caste system.” The Courier drew from the report of the Colored Advisory Flood Commission, appointed by Herbert Hoover and chaired by Tuskegee University’s Dr. Robert R. Moton. The report found that white landlords were supported while Black peasants and share-croppers suffered. Meanwhile, the National Guard was deployed to maintain “law and order” and to prevent Black people from leaving flooded territory.

The title of the Courier’s editorial was “Even During Disaster,” pointing to the fact that extreme events and ecological emergencies could not erode the edifice of whitesupremacy. As more and more of the events occur, it is something Black folk need to remember now. We reprint the Pittsburgh Courier’s editorial below.

Even During Disaster

Pittsburgh Courier, December 31, 1927

Ordinary sense of decency, honesty and fairplay ought to have impelled the whites in the Mississippi Valley to dismiss considerations of color during the relief of the sufferers from the recent flood. For once the element of race should have been laid by the board, at least until the district got back to normal. Because all were human beings and citizens of the United States, they should have had their needs administered to with absolute equality. Because Negro labor constitutes at least ninety per cent of the available supply, intelligent self interest out to have dictate a policy of non-discrimination in the granting of relief and the care of sick and homeless, for the reconstruction of the area depends upon the rehabilitation of the working population, almost all of which is black.

But such was not the case. The whites of the Mississippi Valley ran true to form. Neither disaster, catastrophe nor calamity can take precedence there over the color-caste system. As all other public “accommodations” are divided “for white” and “for colored,” so was the flood relief. The waters receded only to find the spirit of Jim Crow hovering over the historic valley as of yore, with the National Guard and the Red Cross doing his bidding. Not satisfied with forcing Negro labor to do the bulk of the work on the levees in an effort to stem the rush of waters, the noble Caucasians of the area proceeded to neglect the homeless black population even before the waters had begun to recede. Whites, as usual, came first. Where was Mr. Hoover all this time?

Such is the report of the Colored Advisory Flood Commission to Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, and Vice Chairman James L. Fieser. It was mild weather and not the ministrations of the relief forces that kept the Negroes from suffering more than they did. Although the national Red Cross specifically instructed that the flood relief was to go directly to tenants and sharecroppers, local officials looked out for the landlords first and grudgingly gave the black peasants what was left. The greatest attention paid to the black population was to prevent as many as possible of them from escaping to civilized territory. For this purpose the National Guard, called ostensibly to maintain order, was used freely and generally. Says the report, “We found our people densely ignorant, cowed down by white domination, lacking in schools, living in homes scarcely worthy of the name, existing in unhealthy conditions under which they were unable to develop enough resistance to cope with so great an emergency as the flood because they were practically helpless without initiative or self reliance.”

Credit is due the Colored Advisory Flood Commission for bringing these facts to light and to the attention of the national authorities. The report is an intelligent and manly one. Especially is Dr. Robert R. Moton, the chairman of the Commission, to be commended for demanding and getting the resignation of Miss Cordelia Townsend, the white director of relief at Melville, La, for her neglect of colored sufferers and refugees. There were, of course, some instances where the Negro sufferers got a square deal along with others, but in the main, the old American slogan of “white men, women and children first” was sounded throughout the flood area. It was impossible to ignore race and color in that benighted section, even during a great disaster.

“Even During Disaster,” Pittsburgh Courier (December, 31 1927)