As part of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum, we interview scholars about a recent article they’ve written for either an academic journal or popular publication. We ask these scholars to discuss their article, as well as some of the books that have most influenced them.

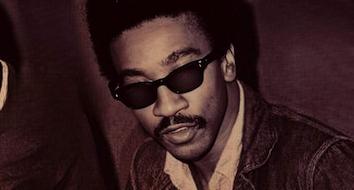

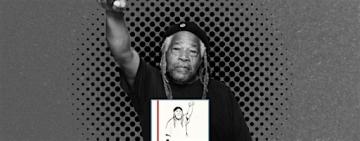

This week’s featured scholar is Akinyele Umoja. Umoja is Professor of Africana Studies at Georgia State University. His article is “Maroon: Kuwasi Balagoon and the Evolution of Revolutionary New Afrikan Anarchism.” The article can also be found in the book, A Soldier's Story: Writings by a Revolutionary New Afrikan Anarchist.

Why is it so important for students of Black liberation to study the history of freedom fighter Kuwasi Balagoon?

Kuwasi Balagoon is one of the most heroic and remarkable figures of the historic Black Liberation struggle. He was born Donald Weems in 1946 in the predominately Black community of Lakeland in Eastern Shore, Maryland and was inspired by the powerful Gloria Richardson and the Cambridge (MD) movement in his youth. One of his first acts of resistance was fighting racist soldiers in the military after he joined the u.s. army. Weems moved to New York after being discharged and there went through a political and cultural transformation. He changed his name to Kuwasi (Ewe for “born on Sunday”) Balagoon (Yoruba for “warlord”) and became involved in tenant organizing in Harlem.

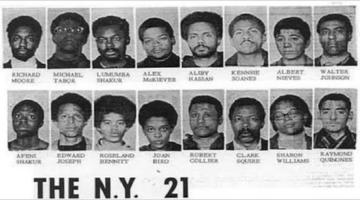

He embraced the politics of revolutionary nationalism and joined the Black Panther Party (BPP) for Self-defense in New York in 1968. The BPP in New York was growing into a vibrant revolutionary nationalist force building on the legacy of Marcus Garvey, Balagoon, and other powerful radical and Black nationalist activists in the city. To stop that momentum, key New York BPP leaders were arrested in April 1969. This is what came to be known as the case of the New York Panther 21. Balagoon’s case was severed from his other BPP comrades, who were acquitted of all charges. Balagoon escaped from imprisonment and ultimately became part of the revolutionary Black underground – the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Many other rank-and-file members of the BPP joined the BLA. As a BLA member, Balagoon helped “liberate” other comrades for imprisonment and expropriated funds from u.s. financial institutions to support the Black liberation movement in the u.s. and anti-colonial struggles in Africa, particularly in Zimbabwe.

One of the unique aspects of Kuwasi Balagoon is his ideological identity as a New Afrikan Anarchist. He believed that the descendants of enslaved Afrikans in the united states (u.s.) deserved independence and their own territory from our historic homeland in the southeastern part of continental u.s. empire, also known as New Afrika. He was also opposed to authoritarian and hierarchal forms of governance.

Can you share a little about how Balagoon developed a more anarchistic approach to Black struggle?

Balagoon became critical of the Oakland-based BPP hierarchy when he was a political prisoner in the New York Panther 21 case. As I previously mentioned, the New York 21 were key leaders of the NYC BPP chapter who were arrested or forced into exile due to conspiracy charges designed to eliminate their effective organizing and influence. Though this was a high-profile case, the NY Panther defendants thought their national leadership was not providing them with adequate support and making their legal defense a priority. They were also troubled by the lack of support and even condemnation of the national BPP leadership for captured comrades who engaged in guerilla warfare against the imperialist state and capitalist institutions. BPP Southern California chapter Minister of Defense and former Army Ranger Geronimo ji Jaga (Pratt) is one captured comrade that the NY 21 and other rank and file BPP believed that national leadership abandoned after his arrest. Another critique of the national BPP leadership occurred when it imported an authoritative overseer to monitor and guide the work of the New York chapter. Balagoon and other NY BPP cadre saw the dispatching of outside managers as a vehicle by the Oakland-based authority to control their chapter and to oppose the New York BPP developing its own indigenous leadership.

Like his co-defendants and the NY chapter members, Kuwasi also believed the national BPP leadership was autocratic and ultimately moving away from revolution. He thought the national leadership had become an oligarchy and had distanced itself from the rank-and-file BPP member. This critique motivated Balagoon to examine other forms of revolutionary organization than democratic centralism, which was the BPP organizational framework, and ultimately embracing anarchism as a process and ideological framework.

Balagoon both escaped from prison and risked his life to break friends out of prison. How does this reflect Balagoon’s radical commitment to guerilla warfare and Black liberation?

Kuwasi Balagoon believed that guerilla warfare was a legitimate means to achieve Black liberation and revolution. He also thought that liberation would be achieved through a “protracted” campaign of guerilla warfare. Kuwasi believed the u.s. government was illegitimate, and that oppressed people had the right to use any means available to them to be free. He defined himself as a prisoner of war after his capture and saw it as his right and responsibility to escape. International law supports the human right of prisoners of war to escape their captivity. After his escapes, he worked to free others on more than one occasion, including his participation in the liberation of Assata Shakur from prison in 1979.

How did Balagoon’s time as a political prisoner shape his larger commitments to anarchism and revolution?

Balagoon’s experience in captivity also influenced his political embrace of anarchism. He and other members of the New York 21 were held in different facilities in boroughs throughout New York city. They participated in a “coordinated rebellion” of prisoners in 1970. Balagoon was a prisoner in the Queens House of Detention, where insurgent inmates held seven hostages (of correctional officers and jail staff). Their demands included humane treatment for prisoners and their visitors; the free supply of soap, toothpaste, and towels; and speedier trials. The rebellion was organized through the formation of committees to coordinate the distribution of resources and decision-making through consensus. This experience made an impact on his political consciousness and transition towards anarchism. The uprising was ultimately crushed after the decision was made to release the hostages (thus losing leverage). While this was a defeat, Balagoon saw the potential of how prisoners organized the rebellion as a model for struggle.

What kind of organizing was he involved in while incarcerated?

Kuwasi Balagoon viewed and conducted himself as a prisoner of war. He did not see himself as a criminal or convict but as a captured soldier of a revolutionary struggle. Balagoon worked with other political prisoners to form study groups to develop themselves and also provide political education and organization of other prisoners during his captivity. He also recruited other prisoners into the revolutionary underground wing of the movement. Some of his recruits participated in revolutionary actions after their escape or being released from captivity. He also maintained communication with revolutionary New Afrikan nationalist, anti-imperialist, and anarchist collectives, engaging in ideological struggle and offering solidarity statements to support the work of comrades on both sides of the walls of captivity.

What lessons does Balagoon’s story offer for communities wishing to confront heteronormative ideologies in Black social movements?

Homophobia remains a counterrevolutionary and anti-democratic ideology in our community and in the Black liberation movement. Kuwasi Balagoon’s life as a bisexual man challenges the false narrative that queer folks can’t be “soldiers” and assumptions about who can be a revolutionary and freedom fighter. You can’t be more of a resistance fighter than Kuwasi Balagoon was! The fact that other revolutionary soldiers worked with him on the basis of mutual love and respect also provides an example of comradeship between folks of diverse sexualities.

A lot of organizers, artists, and academics can often point to books that helped radicalize them. Are there any books that radicalized you? How so?

The Autobiography of Malcolm X was critical in making an impact on my consciousness when I was a pre-teen. I should also note that the Black Panther Party newspaper and The Black Scholar were important. Articles by Max Stanford (aka Muhammad Ahmad) in The Black Scholar were critical ideological formation and much of what I believe today. Finally, as a pre-teen I read a biography of Muhammad Ali that had an impact on my political orientation. I would also read entries in the Encyclopedia Britannica Book of the Year on radical figures like H. Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, Frantz Fanon and Che Guevara. While I had difficulty contextualizing it, in the 9th grade I did a book report on Che’s Bolivian diary. My world history teacher, a young Black woman, raved over my report and used it as a model for her other students.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.